March and April 2024 mark a grim anniversary: four years since half of humanity went into lockdown as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak. During the frightening and stern months of the pandemic, a catchphrase animated policy discussions and provided reasons for hopefulness: “building back better."

After four years, it is now possible to take some measure as to how much this aspiration has been fulfilled.

The latest 2023/2024 Human Development Report argues that the world is falling short. The evidence comes from the post-2019 evolution of the Human Development Index – one of the metrics of human development published in the report. The Human Development Index (HDI) is a composite of indicators measuring standards of living and achievements in health and education. The report presents the HDI for 193 countries since 1990, as well as several aggregates, including by region, by HDI groups (low, medium, high, and very high) and globally.

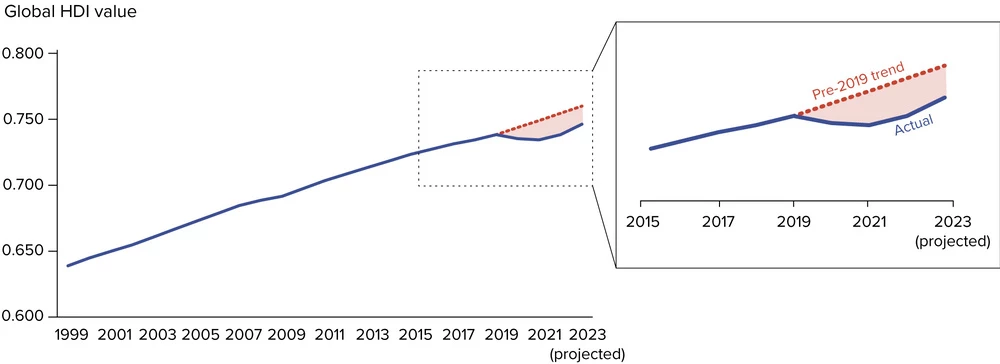

The global HDI is in uncharted territory. Its evolution up to 2019 was a story of steady progress, until it suffered a decline in both 2020 and 2021, before improving again in 2022 and being projected to continue to improve in 2023 (see figure below). However, the evolution of the global HDI value now sits below the pre-2019 trend. If the evolution of the global HDI remains below trend, this purports the potential for permanent losses in human development.

While the potential for permanent “scarring” during economic downturns is increasingly recognized in the literature and in policy practice, there has not been as much attention to the potential permanent scarring of human development prospects. Pre-2019, the global HDI value was on track to take the world above the threshold defining a very high level of human development (0.800) by 2030 – the target date to meet the Sustainable Development Goals – but this is now out of reach until much later.

But it gets worse. During the 2020-2021 period about 90 percent of countries suffered declines in their national HDI, and about 30 percent of those that witnessed a decline during those years are not projected to reach their pre-2019 HDI value in 2023. Moreover, while all OECD member countries are projected to have reached or surpassed their pre-2019 HDI levels, only half of the least developed countries are projected to do so.

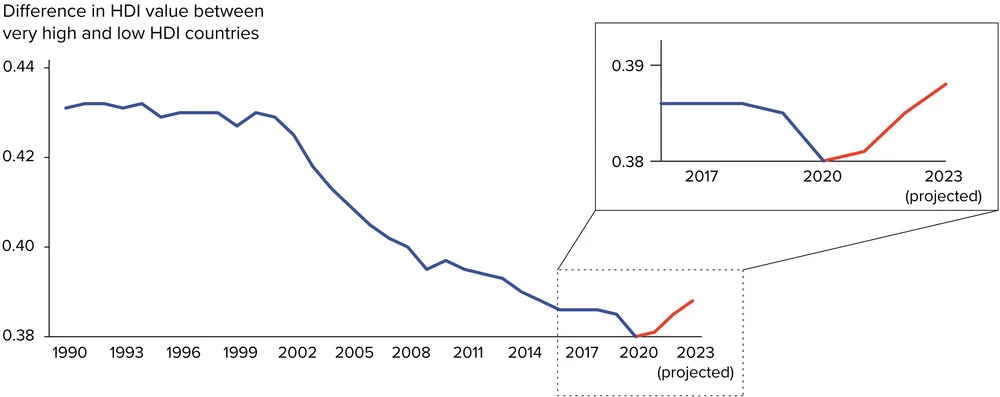

Also concerning is the fact that the gap between the very high and low HDI groups of countries has been increasing since 2020: divergence, big time, reversing a trend of convergence sustained for decades (see figure below). Consistent with other evidence, so much for leaving no one behind, a central pledge of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

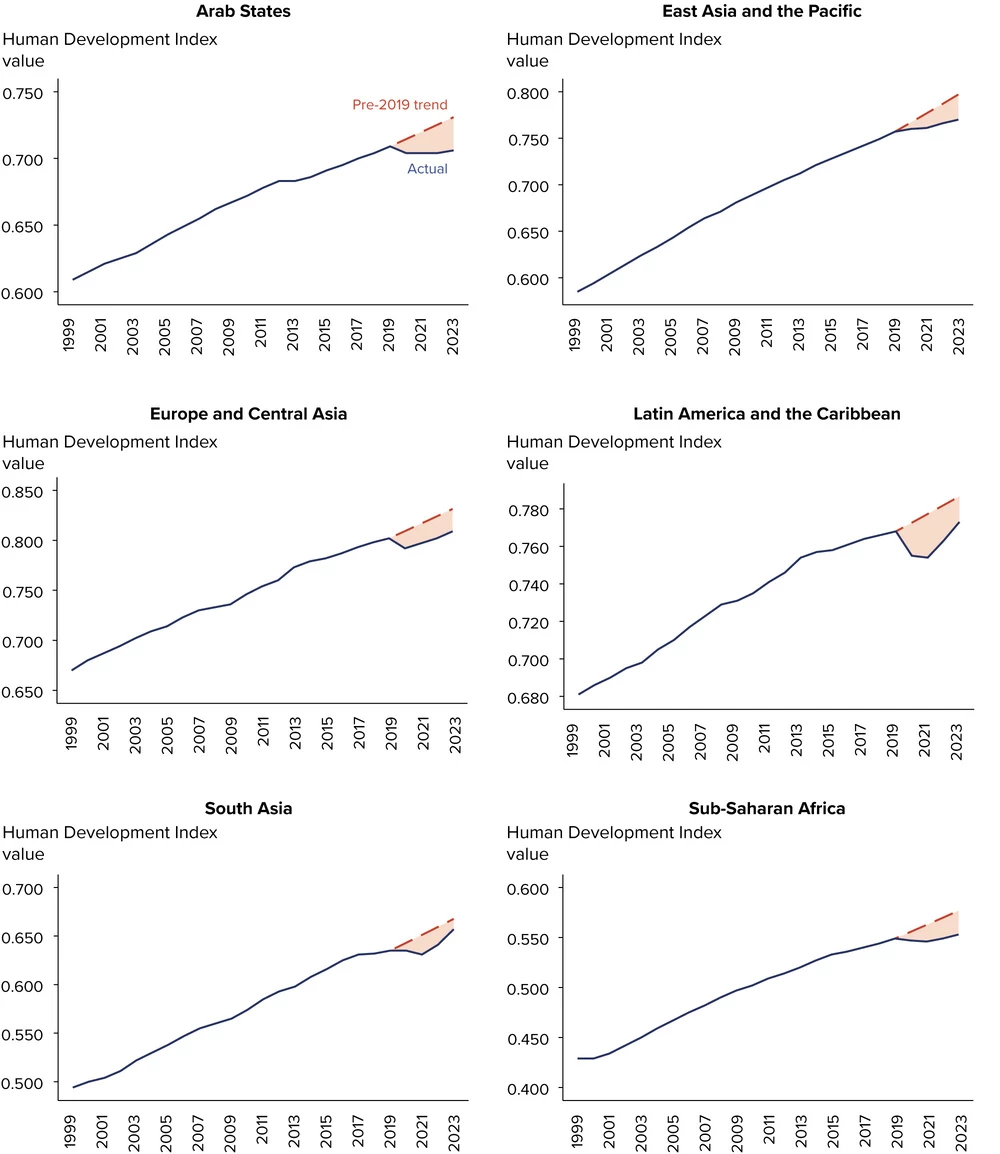

Every region in the world is project to fall in 2023 below their pre-2019 path, with some regions, such as the Arab States and Sub-Saharan Africa, registering little to no improvement in the regional HDI (see figure below).

So, are meeting the aspirations based on the 2030 Agenda and the promise of building back better? The potential of permanent losses in human development, with the poorest and most vulnerable of our international community being left behind, strongly suggests that the world is falling short. The latest 2023/2024 Human Development Report provides an interpretation as to why this may be happening, and what to do about it. Tracking the HDI at multiple scales is one way of assessing whether the world will succeed.

Join the Conversation