There are now over 114 million people who have been forcibly displaced by conflict, violence, or volatility in the world. However, this figure does not wholly depict the difficulty of their human experience—behind each number there is a mother, father, son, or daughter, whose life has been disrupted or destroyed.

Data—particularly microdata, such as household surveys—can help by painting a picture of the life of everyone in detail, but also about the challenges they face: food security, shelter, access to water, health care, education, and livelihoods.

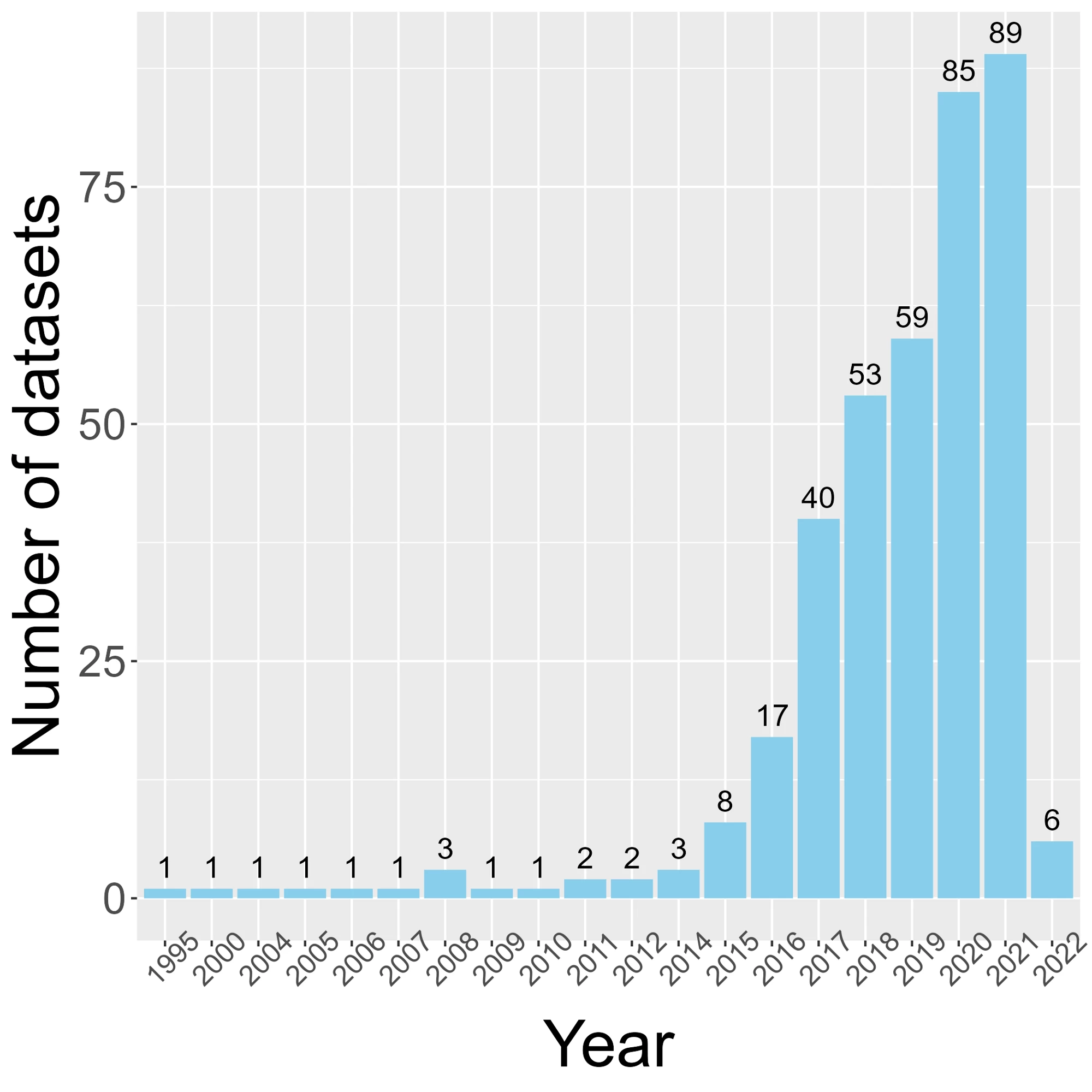

The World Bank-UNHCR Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement has undertaken a review of all publicly available household survey datasets from the two largest databases of microdata (the World Bank and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees microdata libraries) from 1995 to 2022.

The result is Forced Displacement Microdata, a dashboard where users can view the data overall, as well as access individual datasets.

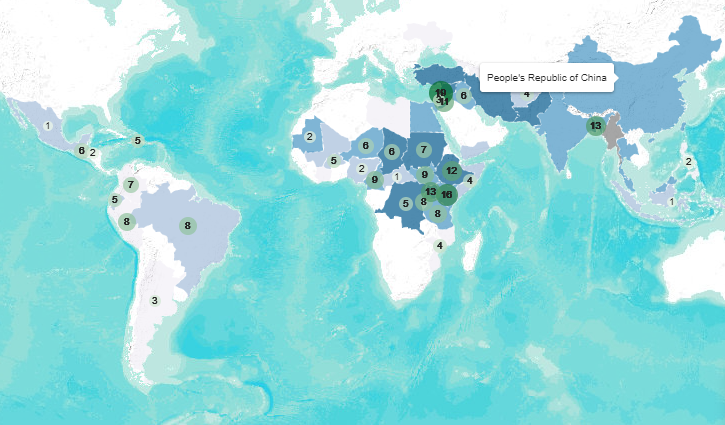

The 375 datasets account for a representative sample of refugees or internally displaced people (IDPs) from 53 low- and middle-income countries. The analysis (detailed in the World Bank Paper, "Data Gaps in Microdata in the Context of Forced Displacement" revealed three main findings:

1. Microdata on forcibly displaced people has been increasing, but is highly uneven

Data is relatively rich in Sub-Saharan Africa—particularly in East Africa—compared to other regions. Data is particularly scarce in countries that have endured years of conflict and fragility, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Syria, and Yemen.

2. Data scarcity is particularly pronounced among internally displaced people

One of the most startling gaps is the lack of representative data on internally displaced people (IDPs). Of the 221 datasets on forcibly displaced people collected since 2010, only 22 have a representative sample of IDPs. Currently, IDPs comprise approximately 60 percent of all forcibly displaced people. Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Syria, Türkiye, and Yemen all have more than one million IDPs, yet none of these countries have datasets with representative samples of them.

3. Data on labor outcomes is very limited

Employment is a cornerstone for rebuilding lives. Some studies find that labor market access not only increases a person’s self-reliance, but can also improve social cohesion among nationals and recently settled populations such as migrants and refugees. More data on labor and employment is necessary to support effective policies and governments’ efforts to improve livelihood opportunities for the forcibly displaced.

Although these gaps persist, the data contained in Forced Displacement Microdata is evidence that there is a lot more data on forcibly displaced people now than there was ten years ago, and a wealth of it is available to the public.

The more data we have on forcibly displaced people, the more we can try to ensure that over 114 million displaced do not remain statistics. The gaps that do exist illustrate the kind of data that is still needed—and by addressing these gaps, we can help improve policies and programs to better meet the needs of everyone affected by forced displacement.

Join the Conversation