Nigeria faces a serious poverty-reduction challenge: Almost half of Nigerians are estimated to live below the national poverty line. However, unemployment is less than 5 percent. But even when many Nigerians are working, they remain poor. In fact, poor and non-poor Nigerians are about equally likely to work. To escape poverty, it is more important what someone does, rather than whether they work.

Therefore, effective poverty-reduction policies need evidence on the quality of jobs in Nigeria. Fortunately, the new Nigeria Labour Force Survey (NLFS) provides detailed information on the activities in which Nigerians engage.

To begin, the overall type of work people do—be that wage- or self-employment—is strongly associated with poverty. Those holding wage jobs are far less likely to be poor.

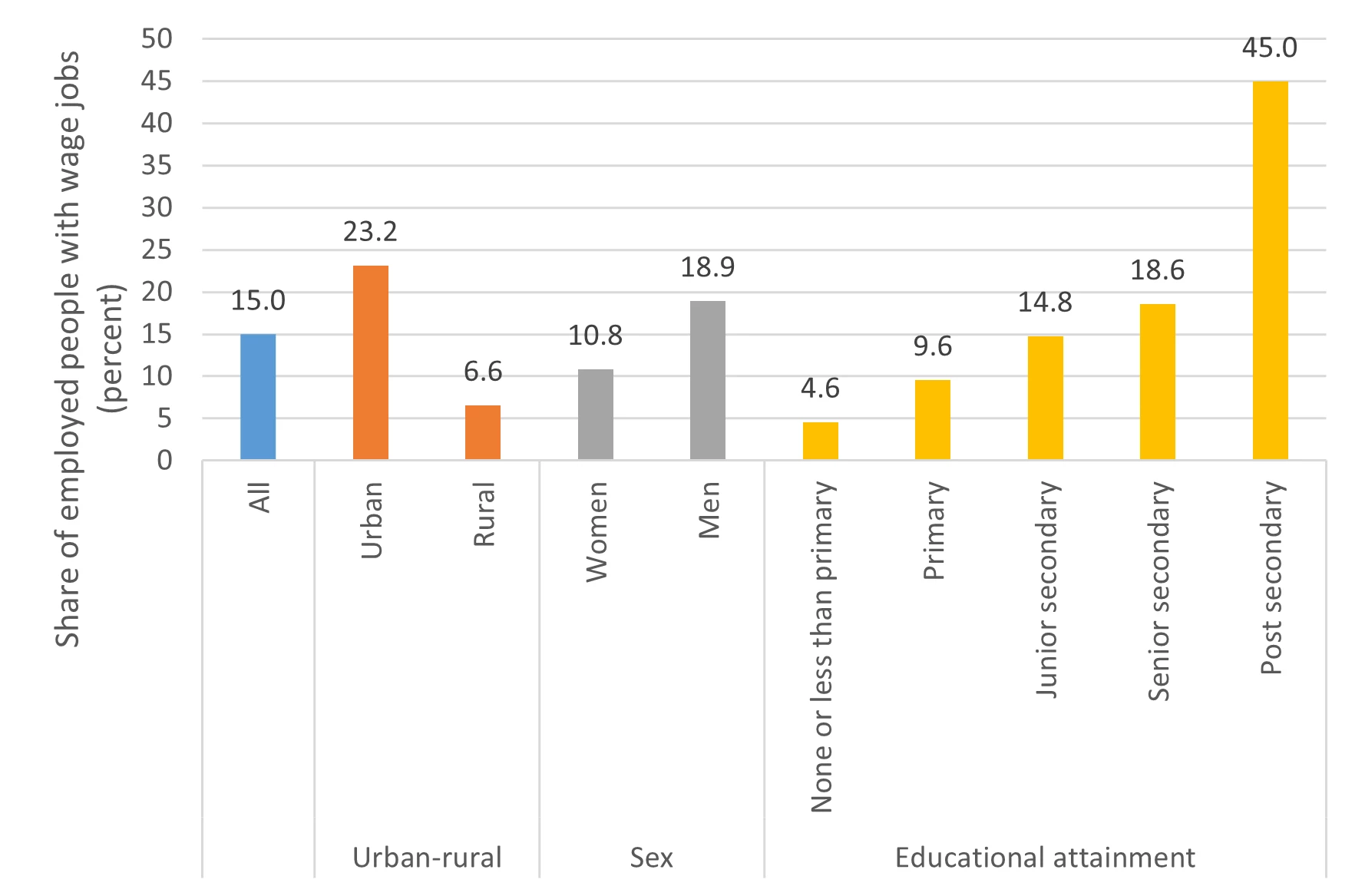

However, wage jobs are scarce in Nigeria. Only around 15.0 percent of employed Nigerians engage primarily in a paid wage job or an apprenticeship. More education certainly helps to obtain wage work, but offers no guarantee: less than half of Nigerian workers with post-secondary education manage to get a wage jobs.

Figure 1. Share of employed Nigerians primarily engaged in wage work by urban-rural, sex, and educational attainment, 2022/23

Moreover, most wage workers do not receive additional job benefits. Less than half of Nigerian wage workers have written contracts, only around one quarter work for employers that make social security contributions, and just one-fifth have paid leave.

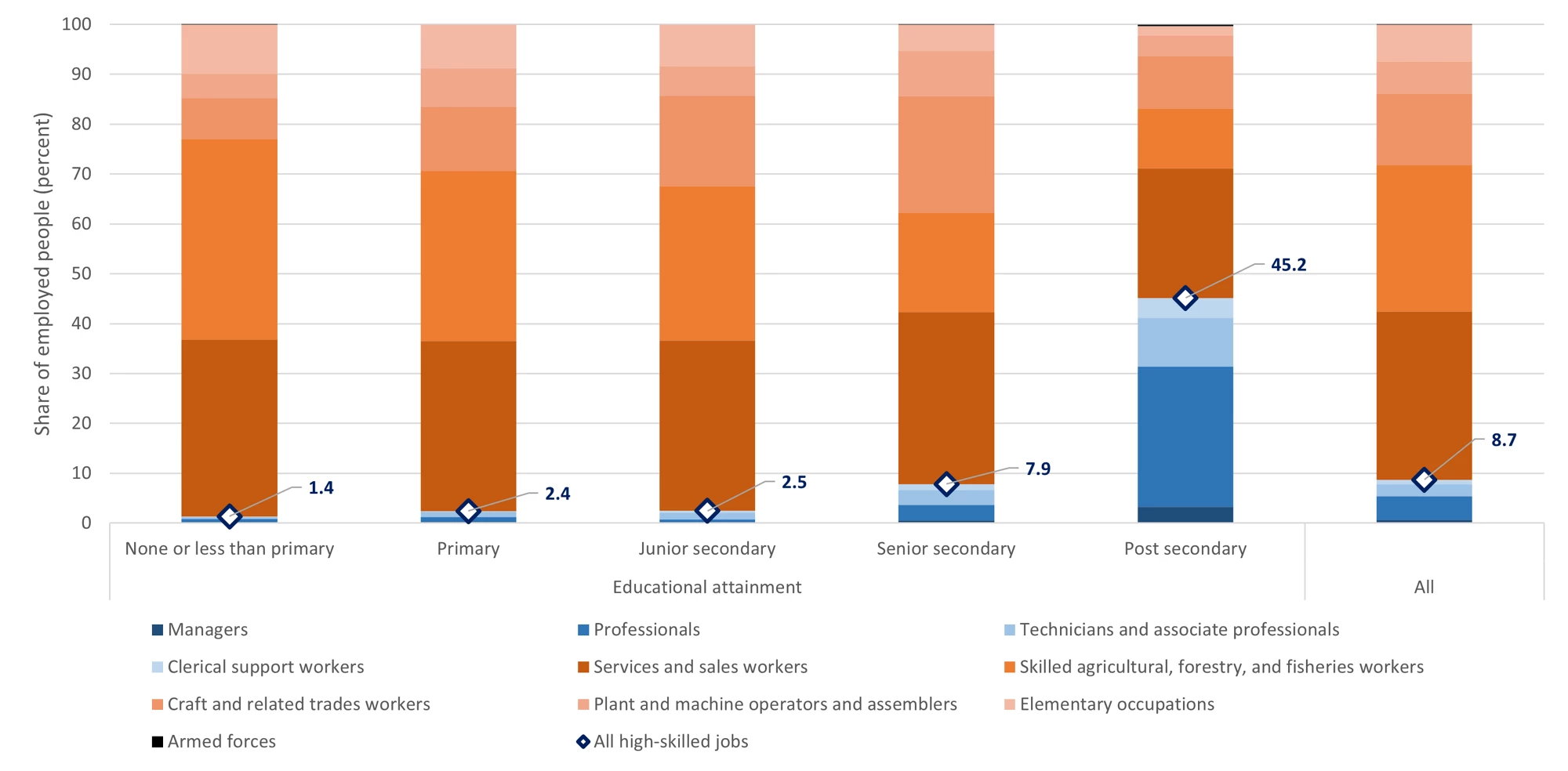

Most jobs—wage or non-wage—do not necessarily utilize high skill levels, even for those Nigerians with secondary and post-secondary education. Only 1 in 10 workers are managers, (associate) professionals, technicians, or clerical support workers—occupations which use advanced skill levels.

Not surprisingly, most of these jobs are held by Nigerians with post-secondary education. However, even among them more than half are not able to land such a job. Thus, either the skills acquired by post-secondary education do not match the needs of employers, or such jobs are too scarce in Nigeria’s economy.

Figure 2. Primary occupations of employed Nigerians by educational attainment, 2022/23

Indeed, more than three-quarters of employed Nigerians work in establishments that engage fewer than five people. Management of and specialization in complex tasks is usually not possible in such small establishments, limiting the demand for high-skilled labor. Lack of access to finance and infrastructure keeps firms small, constraining their growth and—with that—also their ability to create higher skills jobs through specialization.

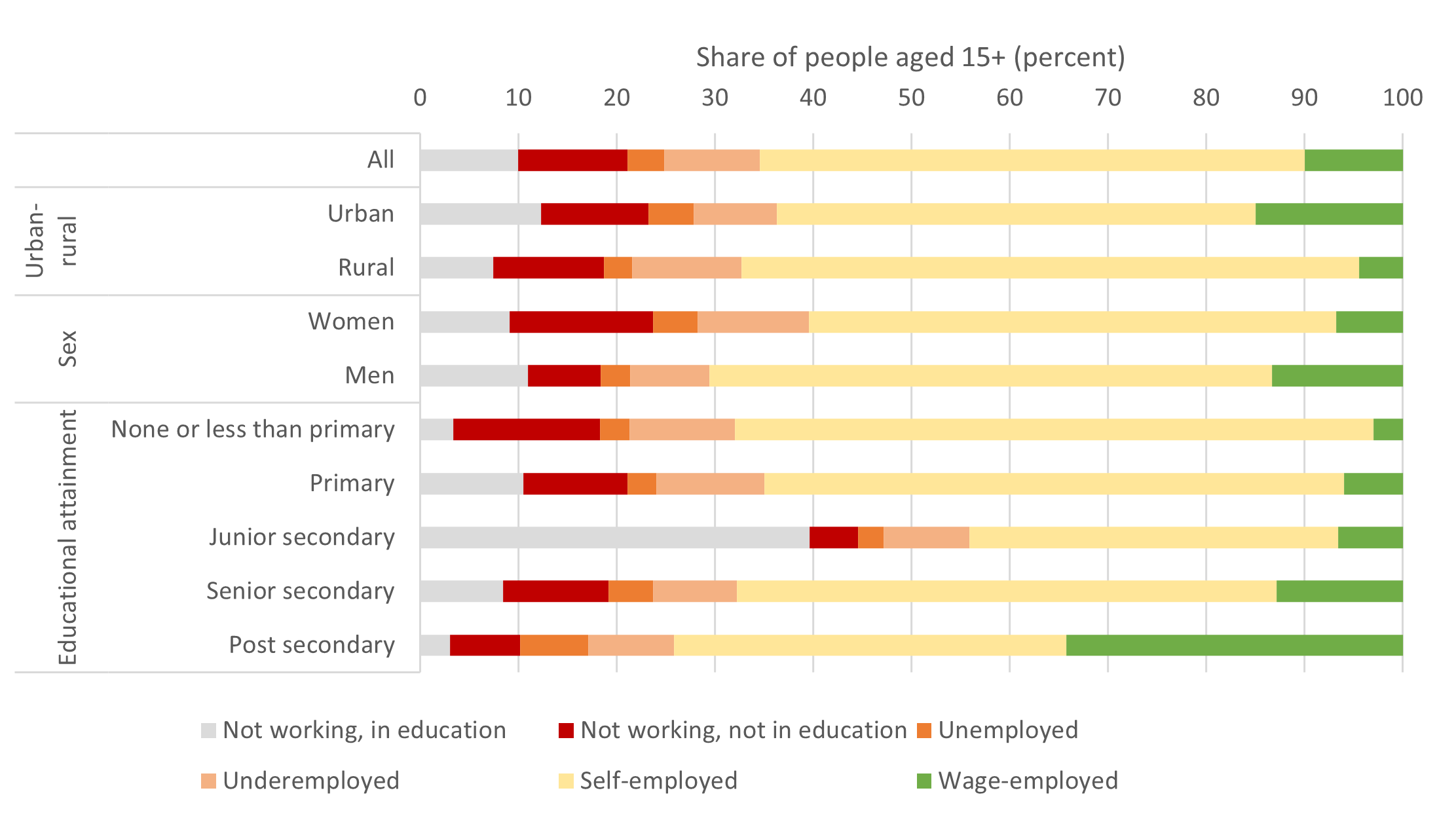

Not only the nature of the job matters, but also how many hours one can find work. Many employed Nigerians cannot get enough hours of work to meet their income needs. Around 13.0 percent of employed Nigerians work less than 40 hours per week but are willing and able to work more—they are underemployed. While nearly one quarter of employed Nigerians take on secondary jobs to supplement incomes, many others are not able to find a secondary job.

Summarizing Nigeria’s labor market, underemployment and lack of wage work or other high-quality jobs are far more widespread issues than unemployment. Education helps, but it is no guarantee for a good job, and the skills that firms need but which workers can provide may be mismatched.

Figure 3. Employment status of working-age Nigerians, 2022/23

Rather than just creating more jobs, Nigeria needs policies that can support firm growth to expand wage jobs, build productivity in farm and non-farm household enterprises, and help match the skills of school leavers with those that the economy needs most. Tracking job quality and productivity provides more lucid policy focus than simply seeing what happens to the unemployment rate.

Fortunately, going forward, Nigeria’s strong investment in labor market data will shine a light on the labor market policies that can address the country’s urgent poverty-reduction challenge.

Join the Conversation