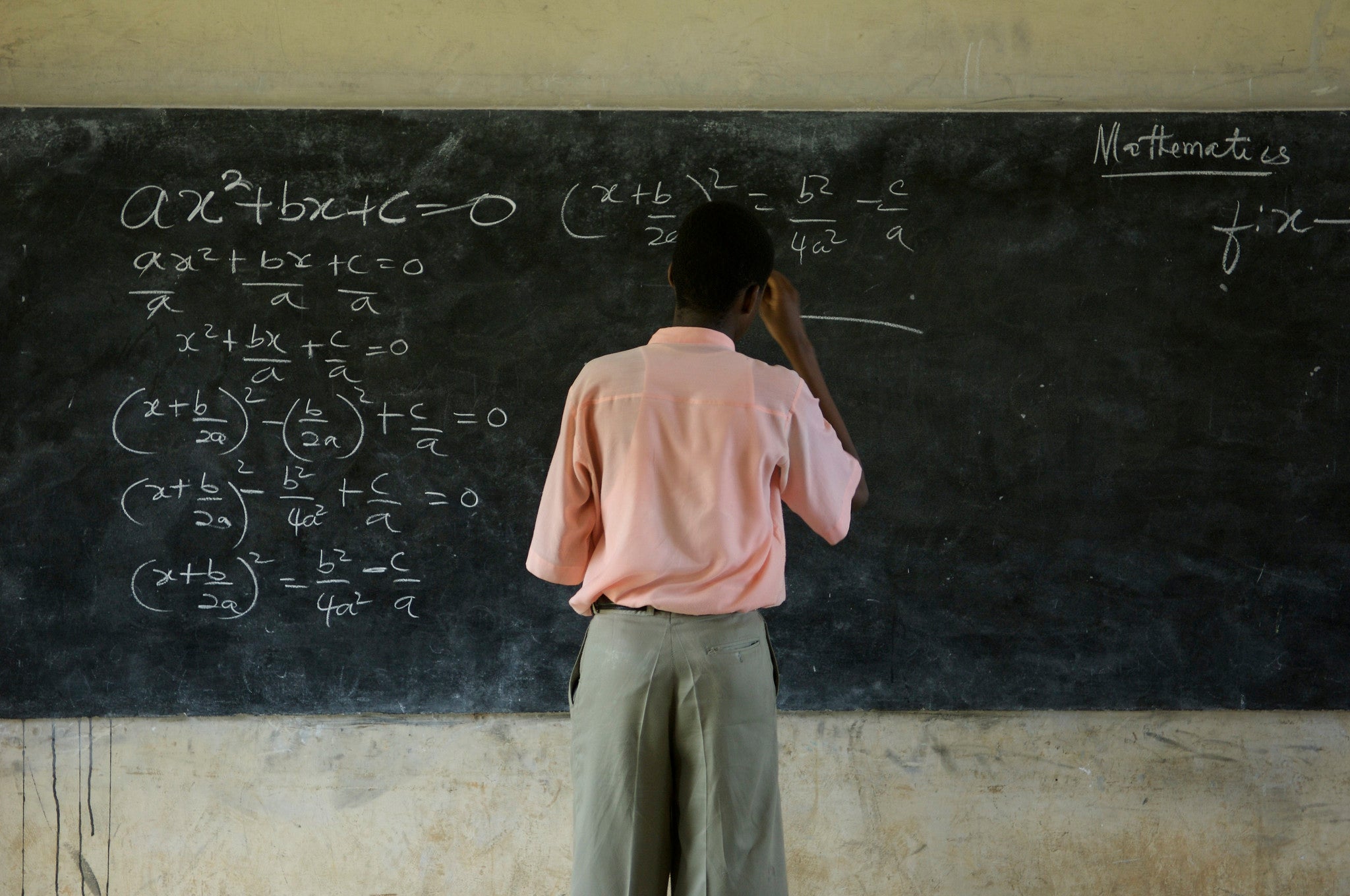

A student solves a mathematics equation

A student solves a mathematics equation

Migrants often use the phrase ‘giving back’ to describe their motivations for making money and in-kind transfers back to their countries of origin. They send ‘individual remittances’ to support the daily life of family members, and ‘collective remittances’ to improve conditions for others in their homeland communities. Their collective contributions are usually sent for the provision of education, healthcare, and social welfare services, and to develop community infrastructure facilities.

A recent study at SOAS, University of London, examining money transfers along the UK-Nigerian corridor, points to the need for further research on the impact of remittances on the education landscape. This is particularly important as the government’s funding of education is inadequate. The effects of the funding gap can be seen in schools with insufficient educational materials, equipment and facilities.There is also a high-level of staff dissatisfaction, resulting in regular strike actions especially among university staff.

Nigerian diaspora communities are making tangible impact on the soft and hard infrastructure of the education system in Nigeria . In the five-year period prior to the research survey, participants had contributed an average of £210 yearly in support of their alma maters. The money they send are to provide scholarships and grants to indigent, and outstanding students; and to hire teachers where there are shortages.Their in-kind contributions include books, computers, medicines, sports equipment and facilities, and the provision of training opportunities. They also complement the government’s provision of classrooms, libraries, laboratories, hostels, kitchens,health centres, water and electricity supply, and access roads. All of these interventions help to create a more conducive learning environment in beneficiary schools, and to boost the morale of staff and students.

However, in spite of the widespread nature of their involvement in schools, the diaspora’s support is rarely addressed in the migration-education literature on Nigeria. Also, there is no specific acknowledgement of their benefaction in migration policy documents. This is puzzling as inspectors from the education ministries, and the management teams in schools are aware that diaspora members participate in alumni relations. The ambivalence raises the question whether the diaspora’s efforts are not considered to be important, or they have simply been overlooked for the following reasons.

First, collective remittances are raised from member fees and donations in hometown and alumni associations where the diaspora live. Often, these groups have limited capacity for fundraising and project delivery; therefore, they are regarded as trivial institutions whose contributions are not notable. However, there is rich qualitative evidence showing that the impact of the diaspora is far greater than their material outputs suggest.

Second, the diaspora’s contributions pose a challenge to existing definitions of development. This is because projects in which they are involved would not normally be regarded as mainstream development projects in western development discourses. Furthermore, policy makers believe more in attracting the academic diaspora to knowledge and skills exchange programmes, than in mobilising general diaspora resources to develop the education sector. These hint at why collective remittances may not have been fully explored in the literature, and why little is known about their impact on education in Nigeria.

Third, diaspora groups often channel education remittances directly through parent alumni associations based in Nigeria. The most common associations are from secondary schools, but there are also old students associations from primary schools, colleges, polytechnics and universities. Often, the parent body combines the diaspora’s donations with those made by alumni living in Nigeria. Also, projects are labelled in the name of the school year or ‘set’ that implemented them. Therefore, the diaspora’s contributions may have gone unnoticed as they are not differentiated from the combined support received.

These specific issues of limited capacity, non-recognition of collective remittances,and the difficulty of ascertaining who is actually involved in donations, contribute to ways in which the impact of education remittances may have been overlooked. They highlight the need to broaden the focus of migration-education research as is the case in Nigeria.

Join the Conversation