As I mentioned in a previous post, the pandemic had an unprecedented impact on public-private partnerships (PPPs) all over the world. Last year, we saw private participation in infrastructure (PPI) investment plummet by 52% compared to 2019 levels, falling to its lowest levels since 2004.

In its first 18 months, the pandemic caused disruptions to the operation of PPP projects and their planning, preparation, and procurement. Reasons for delay or cancellation are not always easy to pinpoint, and COVID-19 could have merely triggered the inevitable for already-troubled projects.

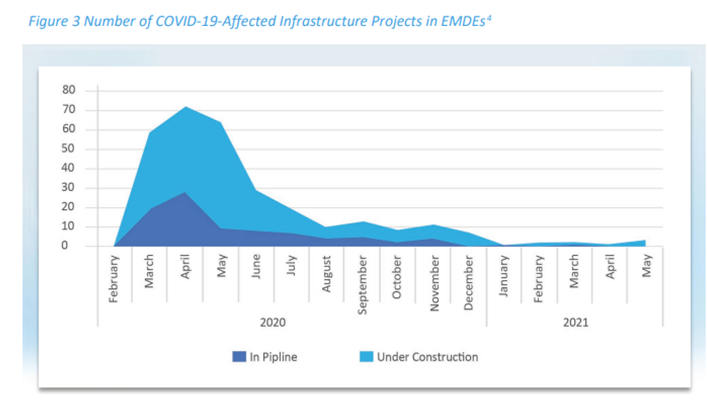

Projects in the planning, procurement, and construction stages, however, were affected by everything ranging from office closures, unavailability of workers, travel restrictions, disrupted supply chains, changed government priorities, and government budget reallocations. At the peak of the disruptions in April 2020, the global PPI database tracked more than 70 projects in emerging markets that were interrupted that month alone.

These disruptions waylaid work that was decades in the making. For example, the Navi Mumbai Airport in India, which already struggled from the start due to delays of environmental permissions and issues in acquiring land from local farmers, was further delayed due to the pandemic. And in Barbados, procurement for a 30-year concession PPP to expand, operate, and maintain Grantley Adams International Airport was delayed due to the "new realities" of the aviation industry.

The impact of COVID on PPPs hit all regions and all income levels. For example, in the United Kingdom, the Western Rail Link to Heathrow, one of the UK's largest rail projects, was put on hold by Network Rail. And in Long Beach, California, a construction firm requested an extension for the development of the Long Beach Civic Center PPP due to the economic uncertainty caused by COVID-19.

Despite these interruptions, there were a few bright spots in 2020 with some PPPs reaching financial close. In the Czech Republic, the €250 million D4 motorway PPP reached financial close ‘in the teeth’ of the second wave of COVID-19, despite a lengthy procurement period. Saudi Arabia announced that the Saudi Water Partnership Company and the Engie-led consortium closed on the Yanbu-5 independent water plant PPP on the Red Sea coast near Madinah, which is the first of its kind, including an $826 million water desalination plant with transmission pipeline.

These examples, and others, highlight that well-planned and well-structured projects, which are flexible in approach, can still attract investment and proceed despite difficult circumstances. Success increases when parties are willing to adapt to changing deadlines, remote negotiations, and where there is a pragmatic approach to risk allocation and availability of government support.

There are signs of recovery that continued to emerge in 2021, when private sector investment commitments to infrastructure increased by 49 percent. However, commitments remained 12 percent lower than the previous five-year average (2016–2020). The rebound in PPI may suggest that recovery is underway, though tight fiscal and financing conditions will require selectivity and attention to quality investments that support multiple economic and social goals such as green, resilient, and inclusive investments. As economic stimulus slows, credit conditions tighten, and uncertainty from overlapping crises intensifies, there will be even greater need for reforms and for scaling private investment in infrastructure. This will require working collectively to enable private sector solutions and putting in place stronger foundations for a post-crises recovery.

For PPPs in particular, the Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF) recently released a series of practice notes that look at how they’ve fared during COVID-19.

What have we learned? Here are some key lessons for the future:

• True partnership is key. Parties must be willing to come together quickly and adapt as needed to changing circumstances to achieve the best outcome for all: project continuance. This is absolutely within the spirit of healthy PPPs.

• Contingency and force majeure events do materialize. It’s important to consider “what if” scenarios for the more uncertain world that could be ahead. This reinforces the importance of good contract drafting and risk management systems.

• Perhaps this is timeless, but it bears remembering: necessity can drive innovation. There are many ways in which the pandemic has made infrastructure and its contracting authorities stronger and more forward thinking. Let’s make sure we’re memorializing them (thanks, PPIAF!) and taking them into the future.

Readers of this blog know that the World Bank is committed to a green, resilient, and inclusive post-pandemic recovery and helping our client countries adapt to changing conditions. They also know that—to finance this recovery—a step change is needed to mobilize more private capital for quality and sustainable infrastructure investment. That is why these lessons from the pandemic are so important: they inform how PPPs can continue to provide better services, more resilient infrastructure, and sustained financing.

Related Posts

New data shows private investment lends a hand as public debt looms large

Time to Step Up: Promoting Regional Infrastructure Integration through PPPs

Private sector financing can accelerate a green recovery for cities

Who finances infrastructure, really? Disentangling public and private contributions

Join the Conversation