At that time, we thought that the crisis would usher an era of durably low interest rates, pushing more pension and insurance investors to pursue a “quest for yields,” increasing mechanically their allocation to non-traditional asset classes such as:

- Private equity/venture capital,

- Real estate,

- Listed infrastructure assets, including infrastructure project bonds and municipal bonds, and

- Non-listed infrastructure – subdivided between debt and equity, each one of these two sub-asset classes being further split between the direct route (long the preserve of large Canadian pension funds) and the indirect way: through specialized infra funds run by U.S., Australian and European asset management companies.

Broad Policy Consensus in Favor of Infra Debt

Infrastructure bond markets (listed infrastructure/fixed income instruments) are more developed in the U.S. (municipal bonds), Canada, the UK, Australia and Brazil, with bond issuances subscribed mostly by domestic institutional investors (pensions, endowments, life insurers) who benefit from fiscal incentives and (partial) default insurance mechanisms. An early adopter among Southern Hemisphere nations, Brazil continues to pursue innovative policies in that market segment – as discussed last year by Joaquim V.F. Levy, then Brazil’s finance minister ( Revista dos Fundos de Pensão. Maio/Junho 2015).

This topic has actually been one of the rare instances of bipartisan consensus between President Obama and a Republican-controlled Congress, which will allow the development of a new kind of federally tax-exempt fixed income instrument called Qualified Public Infrastructure Bonds (QPIB), designed to promote public-private partnerships. And, in the past few weeks, we’ve even witnessed a sharp increase in European and Asian pension investment in plain vanilla US municipal bonds, triggering a rally in this traditional sub-asset class.

But, in potentially riskier jurisdictions, mis-sold bond issuances can have a lasting negative impact on long-term risk perceptions. In early 2016, for example, Mozambique hinted it could default on its $850 million “tuna fishing infrastructure bond” issued three years earlier, which illustrates the flaws around poorly structured deals in certain frontier markets (and deficient fiduciary oversight from the part of foreign investment bankers and asset managers).

An Ideal Asset Class for Long-Term Investors

Further along the risk/liquidity scale, pension and insurance investors are now flocking to non-listed infrastructure debt, either through direct loans extended by large asset owners acting as “quasi-banks” or, more commonly, through infra debt funds. Infrastructure debt could become an ideal sub-asset class, generating stable, recurring returns matching their long-term liabilities while avoiding the complexities and (sometimes hidden) costs occasionally associated with infrastructure equity holdings. Dedicated infrastructure debt funds are being launched in key emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) including Colombia, South Africa, and India – eventually adding fresh sources of capital to diverse sectors (including natural gas mains, renewable energy, and social infrastructure).

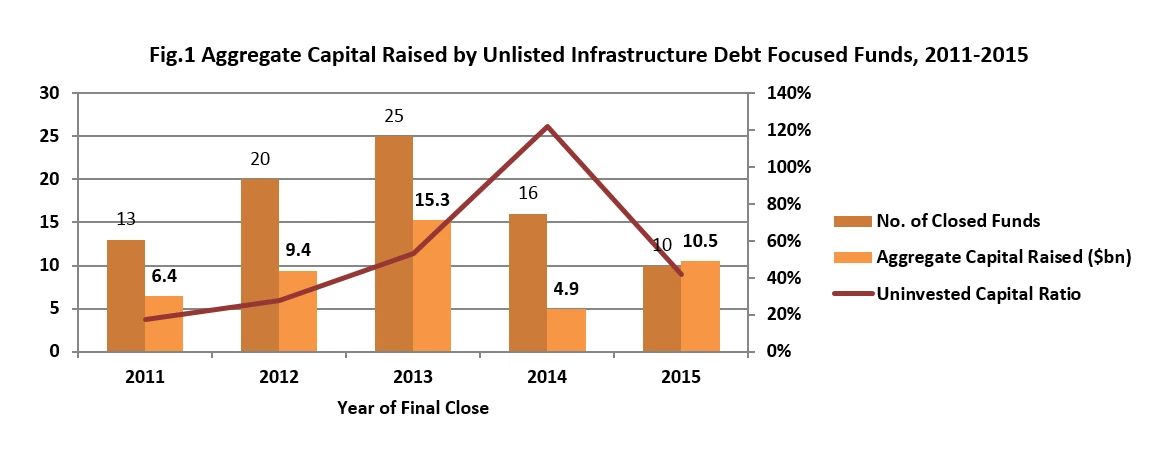

But with too much money chasing too few deals, we run the risk of creating another major supply/demand imbalance. If left unchecked, this could harm both institutional investors and central and regional governments wishing to attract and retain dependable sources of patient capital. By the end of 2014, the Uninvested Capital Ratio (UCR/ see chart), defined as the existing pool of available capital waiting to be invested by infrastructure funds relative to the aggregate capital raised by them for the year, reached 122 percent, a dangerously high level. (It stands at roughly 40 percent today, still a relatively high figure.)

Going forward, it will be important to quench the thirst of institutional investors and avoid such an imbalance within the asset class by helping governments at both the federal and state/municipal level in the Northern Hemisphere, Latin America, Africa, and Asia, where pent-up demand for long-term private capital is particularly strong, and step up the structuration of attractive infrastructure opportunities. Asia alone (excluding China) will need up to $900 billion in infrastructure investments annually in the next 10 years , mostly in debt instruments. This means there’s a 50 percent shortfall in infra spending on the continent.

We can intensify the supply of well-thought-out, investable projects with technical and financial contributions from multilateral lenders, development agencies, and persistent, sustainability-informed asset owners co-investing alongside infrastructure funds and other specialized asset managers. One example is the Global Infrastructure Facility (GIF), which the World Bank Group has launched to offer resources and build out pipelines for partnerships. We’re at the start of a truly long-term trend: the room for growth for the asset class remains high.

Part of this post will appear in the Spring 2016 issue of a European financial economics journal.

Join the Conversation