Beirut under blue sky

Beirut under blue sky

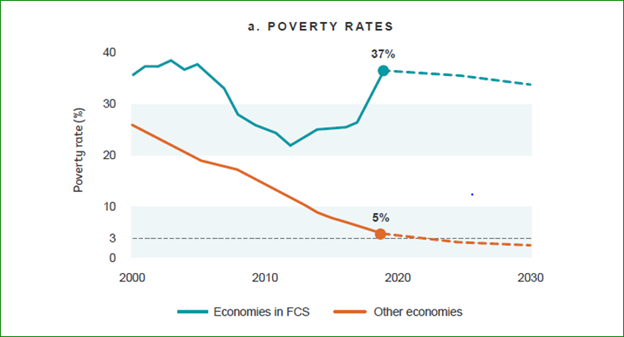

Be it in Burundi, Lebanon, Ukraine or other, fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCS) economies are inhabited by almost one billion people, 335 million of whom live in extreme poverty. As the number of fragile states continue to rise, it is estimated that they will be home to two-thirds of the global poor, by 2030 (figure 1). This alarming trend, along with the eruption of new conflict situations such as the ongoing Ukraine-Russia war, has prompted a stocktaking of ways to promote one of the countering forces of fragility: the private sector and its development.

Figure 1: Poverty Rates in FCS are on an increase

While security – especially for economies engulfed in conflict or post-conflict scenarios – is the sine qua non required for any new investment (public or private) private sector-led development can act as a complimentary force supporting long-term, sustainable economic growth. Private sector development (PSD) can not only help reverse the economic impact of fragility, conflict and violence but also serve as a counteracting force through job creation and re-building public trust and social capital.

The success of PSD is contingent upon creating an enabling business environment, one that is characterized by good governance, predictable and transparent regulations, accountability, inclusion and low levels of corruption, all of which can support business-led growth and help to break free from the “fragility trap”. FCS economies present a challenging milieu for business environment reforms (BER). They are often characterized by weak institutions, political instability and lower levels of private sector development, factors which not only deter business-led growth, but at times also serve to reinforce ensuing fragility and conflict. Governments across majority FCS economies also lack the capacity (and in many instances, the legitimacy) to deliver jobs, effective public services, and opportunities that firms and individuals need –which points toward a strong correlation between countries considered low on government effectiveness and countries considered fragile, per the Fragile State Index (figure 2).

Figure 2: Fragility and Government Effectiveness

Closely linked to weak institutions are corrupt practices and rent-seeking behavior by government officials, which not only impacts service delivery but also erodes public trust. This makes it challenging to effectively implement business environment reforms in ways similar to those that are implemented in non-FCS economies. The challenges to reform implementation are also compounded by higher security costs and limited availability of subject matter specialists on the ground.

In light of the underlying conditions that tend to exist in FCS economies, the report “Business Environment Reforms in Fragile and Conflict Situations: What Works and Why” deliberates upon the design and implementation of business environment reforms specific to such economies. It seeks to answer how such reforms can contribute to the building of stable and resilient societies by helping to develop a vibrant private sector. Some of the findings are observed below:

Understanding the precise nature and severity of fragility and conflict

The nature of fragility and conflict varies across countries (or subnational regions) and is driven by distinct factors such as ethnic fractions, long periods of economic turmoil, and modes of governance (such as authoritarianism or military rule), among others. Policies and reforms focused on creating and improving the business enabling environment — should incorporate tools such as conflict sensitivity and political economy analysis to understand and identify the context of fragility. By doing so, development practitioners and agencies can suggest reforms that take into account sociocultural constraints, while addressing private sector development challenges. Such processes can garner support from public and private stakeholders (such as government and business entities) and encourage acceptance and compliance with new business regulations.

Diagnosing, sequencing and prioritizing business environment reforms

Diagnosing business environment constraints in fragile and conflict affected states may require a different approach (as compared to non-FCS settings). For instance, deploying non traditional means to collect data mobile phone surveys and geospatial imaging.

Any ensuing business environment reform strategy requires proper sequencing, considering the country’s conflict dynamics, economic opportunity, institutional capacity, and willingness to reform. The World Bank Group’s experience in implementing business environment reform in FCS in Sub-Saharan Africa reveals that effective sequencing typically begins with foundational enabling-environment projects targeting the entire economy (such as improving government to business services by putting in place more efficient and transparent company registries, land registries, etc.). Such policy interventions which serve as low-hanging fruit, lend a momentum to the reform dialogue and have led to successful implementation across different regions and settings.

The deployment approach of BER projects also plays an important role in outcomes. Successful projects have always been ones to have ‘greater government buy-in’, which may be either shared monetary or in-kind commitments. A greater government buy-in has led to a higher degree of commitment to ensure successful reform outcome. Additionally, success primarily accrued in projects that were ‘implemented in a cluster and in close succession’. Concentrating resources (i.e., staff on the ground and funding) for use on multiple projects, over a limited time period, within a given FCS area, is more likely to optimize economies of scale and lead to better outcomes.

While priorities differ depending on country context, level of development, and type of fragility, research shows reform priorities to be themes that can serve to counteract elite capture and improve the level playing field for businesses, including the promotion of greater inclusion and social cohesion in FCS contexts.

Adopting an inclusive approach to reforms

Business environment reforms are most successful when they are inclusive and cover all business segments of a population, including ethnic minorities, women, and youth. Inclusiveness is even more important in FCS and post-conflict environments, where divisions within the society are prevalent, and where marginalization of communities is amplified. Consideration should be given to businesses within these groups, including women-owned ones and firms operating in the informal sector. In a context marred with fragility and conflict, encouraging formalization and supporting businesses with high-growth potential to transition out of the shadows should be a key component of a private sector development strategy.

Both conflict-related violence and legal constraints on minorities such as women tend to be amplified in FCS – affecting women much more disproportionately and necessitating increased attention from policymakers. Research has established that inclusive employment and job creation, including one targeting marginalized groups, is one of the most effective means of breaking the cycle of violence.

…and a participatory one

Public-Private Dialogue (PPD) goes a long way in building trust among different stakeholders and ensuring support for sustainable reforms, a trust that is typically eroded in fragile contexts. PPD platforms not only support horizontal reforms in FCS but can also provide a useful starting point to involve the private sector in key sectors, such as agribusiness and extractives, where PPD can help build linkages between large-scale investments and the local economy.

Also, a participatory public-private sector approach prior to and post reforms can help reduce any implementation gaps between de jure and de facto, a common deficiency in fragile contexts due to corruption, favoritism and capture.

Similarly, it is important to develop institutional frameworks to improve cross-institutional coordination, remove bureaucratic redundancies, and ensure greater accountability and transparency while focusing on improving governance and government-to-business service delivery.

Finally, it is imperative to consider that there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution for designing and implementing BER in FCS. Clustering countries by fragility profile reveals significant heterogeneity, which calls for differentiated policy and programming approaches to achieve effective reform solutions. In addition to the type or theme of reform, factors such as how reforms are implemented, and considerations raised by conflict-sensitivity assessments are equally crucial for ensuring the success of business environment reforms in FCS.

Enabling appropriate private sector activities is a means for countries to break free of the “fragility trap” that impedes their progress on economic development. Business environment reforms present a solid opportunity for reaching this goal.

Join the Conversation