With the majority of the world’s population now urban, cities are rising in prominence. Growing attention is being paid to cities’ potential to increase incomes and create jobs – whether through financial services and electronics manufacturing in Chennai, regionally integrated manufacturing around Guangzhou, or social and physical transformation in Medellin. Less prominent cities are asking how they can attain better economic performance. Hence economic competitiveness has become a preoccupation for city leaders – by which we mean a city’s ability to spawn, expand and attract businesses that create jobs for its residents, and to enlarge the overall economic pie.

So, how do cities make themselves more competitive? This year, the World Bank is investing in a Competitive Cities Knowledge Base (CCKB) initiative – a joint project between the World Bank Group’s departments working on Private Sector Development and Urban Development. The project includes in-depth case studies of economically successful cities across all continents. According to our current analysis, six of the most interesting cities for this work will be Bucaramanga (Colombia), Patna (India), Bandung (Indonesia), Agadir (Morocco), Kigali (Rwanda) and Izmir (Turkey). We are in the process of confirming these conclusions before beginning each of the case studies.

What makes these particular cities so interesting?

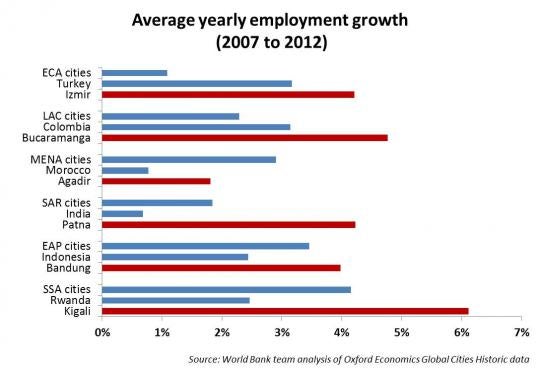

First, they serve as examples of economic success. In fact, according to city-level data from Oxford Economics and our team’s analysis, all six have outperformed their national economies as well as regional competitor cities on economic outcomes such as income and job growth. Indeed, they have recently done so faster than “household names” like Dubai, Rio de Janeiro or New York City. We anticipate these “rising star” cities may offer useful insights for other, comparable cities seeking to improve their economic outcomes.

Second, they demonstrate the use of pro-active strategies that resulted in improved competitiveness. In many cases, leading cities managed to attract an anchor investor, or leveraged a university to catalyze additional investment by firms. We will be investigating the trade-off between city competition strategies that focus on specific initiatives rather than general investment climate reforms.

Third, they are predominantly medium-sized and secondary cities, and thus more similar to the majority of our clients’ cities than the predominant “global cities” literature that focuses on large, primary cities. There already exists a wealth of information on cities in high-income economies that have successfully reinvented themselves (e.g. Barcelona or Boston), or global technological leaders (e.g. Silicon Valley or Austin), or hotspots whose growth is based on unique endowments that are difficult to replicate (e.g. Singapore). How have smaller cities pulled themselves up by their bootstraps?

Fourth, the cities present a diversity of contexts: They are in different regions of the world, including those with varying levels of income and industrial structures.

We’ll present insights along the way as we study our six selected cities. We hope to relate success stories that other cities in developing countries can look to for precedent, inspiration and ideas. Can you help guide our work? What types of insights and guidance would be helpful in achieving success in your cities?

The co-TTLs of the Competitive Cities Knowledge Base Project, Austin Kilroy and Megha Mukim, have contributed to this article.

Join the Conversation