The global economy is stagnating, and uncertainty about its future is rising. These trends weigh heavily on countries that depend on the production and export of a small range of products, or that sell products in only a few overseas markets. Prices of the minerals and other basic commodities that dominate the exports of many poor countries have also declined sharply. All of this points up the need for diversification strategies that can deliver sustained, job intensive and inclusive growth.

The World Bank Group’s Trade & Competitiveness Global Practice (T&C), a joint practice of the World Bank and International Finance Corporation (IFC), is working with a growing roster of client countries eager to achieve greater economic diversification. This is a worthy goal regardless of economic conditions, but especially so now, as developing countries with sector-dependent economies face mounting pressures.

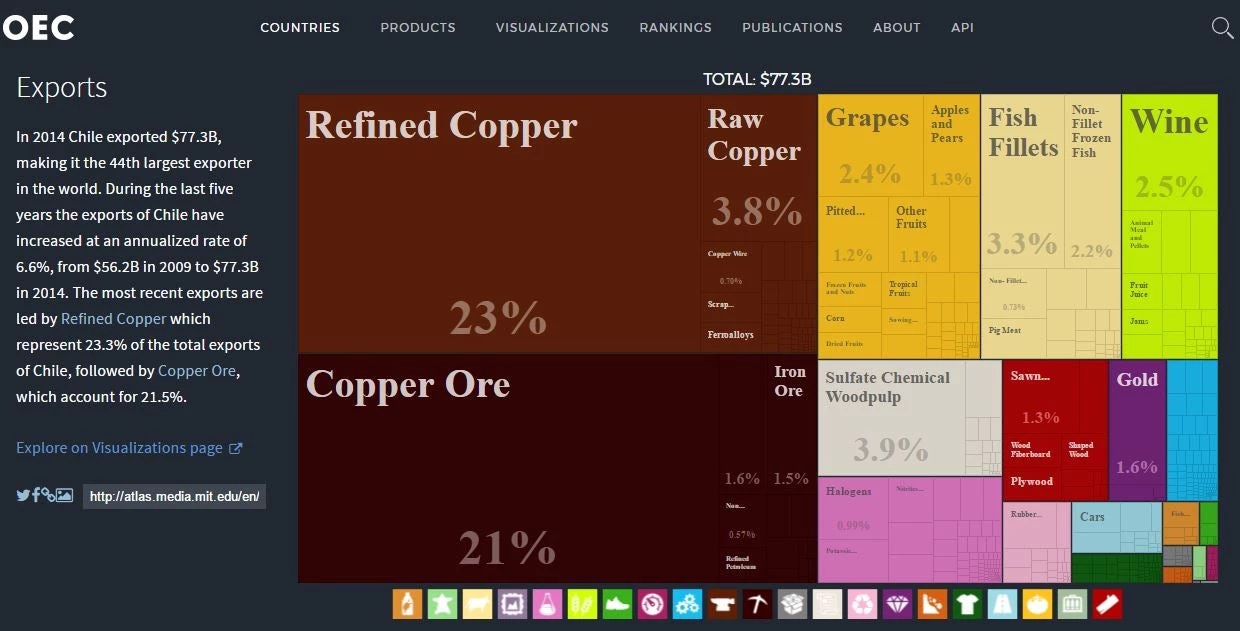

Chile is an example of a diversified economy, exporting more than 2,800 distinct products to more than 120 different countries. Zambia, a country similarly endowed with copper resources, exports just over 700 products — one-fourth of Chile’s export basket — and these go to just 80 countries. Other low-income countries have similarly limited diversified economies. The Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Malawi, for example, export around 550 and 310 products, respectively. Larger countries that export oil, such as Nigeria (780 products) and Kazakhstan (540 products), have failed to substantially expand the range of products they produce and export.

AJG Simoes, CA Hidalgo. The Economic Complexity Observatory: An Analytical Tool for Understanding the Dynamics of Economic Development. Workshops at the Twenty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. (2011)

http://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/profile/country/chl/#Exports

While the sluggish global economy is creating economic problems for traditional exports, other economic trends offer new routes and opportunities for poor countries to diversify. The trend toward the spatial splitting up of production across wide geographic areas, and the emergence and growth of regional and global value chains, offer new ways for developing countries to export tasks, services and other activities. Value chains offer developing countries a path out of the trap of having to specialize in whole industries, with all of the cost and risk that such a strategy entails.

New technologies that have led to steep declines in transport and communications costs have created enormous opportunities for developing countries to export services such as back-office processing. Expansion into these fields not only broadens the base of production, it also diversifies the structure of employment and, especially for women, increases opportunities to find productive work. This is growth that can transform households and countries and boost participation in education — which, in turn, enhances long-term productivity and poverty reduction. E-trade is widening the range of mechanisms by which small producers in developing countries can grow through exporting. Finally, growth in developing countries over the last decade has created the means to reduce dependence on the North American and European markets.

During commodity booms, many resource-dependent countries find it difficult to design and implement public investments and policy reforms that provide a framework for diversification. High commodity prices often lead to overly appreciated exchange rates that undermine the competitiveness of potential new export activities.

Such problems are exacerbated when government fails to attend to distortions in markets for products, services or the factors of production (labor, capital, raw materials and the market for management or entrepreneurial resources). Rent-seeking — for example, by firms seeking government subsidies or other favorable treatment — and a lack of transparency can lead to instability and internal conflict as public and private stakeholders vie for a share of the revenue generated by resource extraction. Governments need to change their regulatory emphasis away from rigid tools governing investment in extractives toward a more flexible approach that encourages investment in a wider range of activities. (For more on this, see the recent blog post by our colleague Akhtar Mahmood: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2017/01/25/unlearning-to-learn-the-path-to-diversification/).

While economic diversification is of particular importance for mineral- and commodity-dependent countries (and even more so in the face of declining commodity prices), it is a challenge for most developing countries as they seek to deliver higher-productivity jobs for growing workforces.

The challenge of economic diversification was discussed extensively during the recent T&C Learning Week, where Bank Group staff, academics, and public- and private-sector representatives shared their experiences pursuing diversification strategies. The discussions made clear that there is no magic recipe for diversification. But they identified a number of elements that provide the foundation for private-sector-driven diversification. These include:

- An appropriate incentive framework based upon a clear, transparent and predictable business and investment climate. Key steps include reviewing trade policies to remove bias against exporting, and ensuring effective competition in product markets and in key services such as transportation, energy and communications.

- Investments in infrastructure and coordinated policy reforms to reduce trade costs. Declining trade costs and increasingly efficient trade logistics were at the heart of the success of East Asian countries in integrating into the regional and global economy and achieving more diversified economies.

- Effective policies to support the reallocation of economic resources to new activities. Of particular importance are labor-market policies and access to finance. These determine the match between workers and jobs, and they help move economies away from declining sectors and from informal economic activity. Success comes by overcoming constraints to mobility, including barriers that limit the entry of women into the workplace.

- Government interventions that target specific market, policy and institutional failures that address shortcomings in the marketplace. For example, information deficiencies and asymmetries, such as lack of knowledge of overseas market standards, are likely to be a key factor behind the comparatively low survival rate of new export flows in developing countries.

T&C assists governments by combining its analytical and advisory capabilities with available lending instruments to identify and support the implementation of investments and policy reforms that provide the essential framework for broad-based and export-driven private-sector growth. T&C’s interventions cover a wide range of activity, from support to cherry farmers in Lesotho to sell their products in new markets, to competition-policy assessments in Tunisia and Peru, to projects to reduce trade costs along key trade corridors linking Côte d'Ivoire and Burkina Faso and communities in the Great Lakes region of Africa, to investment in the development of industrial zones in Pakistan.

Economic diversification is inextricably linked with economic development and poverty reduction, and success will be crucial for many developing countries as they seek to increase the number and quality of jobs in the face of a rapidly rising and youthful working population.

Join the Conversation