How can we successfully design programs to promote financial literacy and financial capability – that is, not just financial knowledge in the abstract, but also the practical skills, attitudes and behaviors needed to take care of one’s everyday finances? Amid the wide-ranging scholarship on financial education, researchers have documented that there is often a strong relationship between exhibiting financial knowledge and achieving good financial outcomes (such as saving for retirement, paying bills on time or avoiding mortgage default). However, there is significantly less scholarship on whether active interventions, aiming to improve financial literacy and capability, actually work.

A paper by Miller, Reichelstein, Salas and Zia 2013, entitled “Can You Help Someone Become Financially Capable?” ( http://www.worldbank.org/financialdevelopment), undertakes a systematic review of the literature on financial education interventions of all types, which includes the use of “meta-analysis” to compare and evaluate the results. They identify 188 papers that present findings on a variety of interventions – the most rigorous and comprehensive evaluation of this literature to date.

Using a meta-analysis is useful in this case, because it is a methodology that facilitates a statistically rigorous comparison of data across independent studies. By pooling data across studies, research findings that may individually point to inconclusive or contradictory results may together yield a statistically significant finding.

In researching financial literacy and capability interventions, meta-analysis can help compare a variety of contradictory and sometimes inconclusive results. However, there are limits to the insights that can be drawn using meta-analysis with a highly diverse literature.objective of the program intervention, the intensity and duration of the intervention, the delivery channels used and the target population.

To make comparisons easier using meta-analysis, and to overcome (at least to some extent) the difficulties posed by the diverse nature of the results, studies were grouped according to the issue they addressed and according to similar outcome (dependent) variables. The most common single-issue topic for financial education interventions was savings and retirement, and the greatest number of comparable papers also address this issue.

The “forest plot” (below) provides observations from six research papers that address the impact of financial education interventions on savings, using a binary dependent variable for increases in savings. A forest plot graphically displays the treatment effects across multiple studies, with a solid line representing the null hypothesis of no effect from the intervention – in this case, from exposure to financial education outreach and training.

In this particular meta-analysis, three of the six papers reject the null hypothesis – that is, they indicate a positive impact on savings from financial education – while the three other papers cannot reject the null hypothesis. Taken together, however, the meta-analysis finds that these papers do provide evidence of impact for financial education. The confidence interval for the pooled data across the six papers is represented by the diamond at the bottom of the graph. It is clearly on the right-hand side of the null hypothesis, rejecting a finding that financial education has no impact on savings behavior. At the same time, the impact appears to be fairly small in magnitude. We lack, however, the data on means and standard deviations to determine the true effect size for this finding, because each study is based on a different level of initial savings, in both absolute terms and relative to income.

My co-authors and I also review the impact of financial education on retirement savings, loan defaults and financial recordkeeping. We cannot rule out the null hypothesis of no impact from the financial-education intervention, either in the case of retirement savings or loan defaults – but they do find an impact on recordkeeping behaviors.

What are some of the reasons for the apparently limited impact from financial-education interventions to date? The World Bank’s 2014 Global Financial Development Report (GFDR) cites several factors that can determine the effectiveness of financial education and outreach – but those factors are in short supply in the studies in the database. These include an attention not only to the information being provided, but also to the way content is delivered. They take into account insights from psychology that may be important for knowledge gains and behavior change.

For example: The delivery channel matters. More entertaining, interactive approaches to teaching financial education are more likely to “stick” than passive outreach, such as brochures or lectures that don’t capture participants’ attention. In fact, there is a growing body of evidence of the importance of storytelling – through books, video or other media – for effective education and outreach ( http://jonathangottschall.com/about-the-book/). One such paper, Berg and Zia 2013 ( http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/1813-9450-6407), discusses the impact that occurred from the inclusion of financial messages in a South African soap opera: “Scandal.” Using a rigorous evaluation, the study shows that viewers of “Scandal” improved their financial knowledge and were less likely, after viewing the show, to engage in risky activities (such as gambling and using costly hire-purchase agreements) than were non-viewers.

However, among the 188 studies in more than half of the cases, the interventions are taught by an instructor in a classroom setting. Other channels used to deliver the content – such as mass media, online tools, individual counseling, phone or print – are all below 10 percent in the sample. A relatively small share of the studies (18 percent) reports using more than one delivery mechanism, although this is considered a good practice by communication and education professionals.

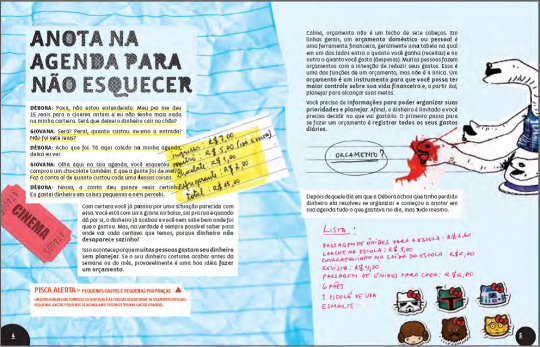

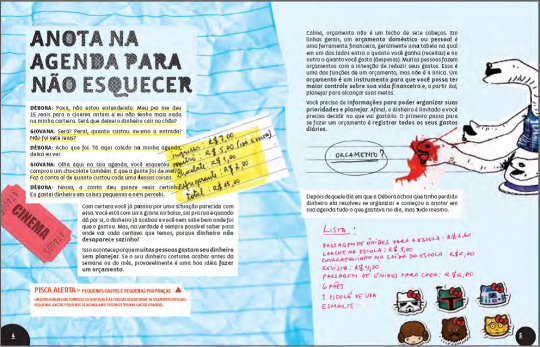

With a good instructor, and with attention to the psychological determinants of financial behavior, however, a classroom approach can be effective. This is the lesson from Bruhn and others (Powerpoint available on http://www.finlitedu.org ) from a forthcoming study of a three-semester financial-education program developed for Brazilian high schools. Program designers included professionals in psychology, and they sought input from students as they developed the materials. The workbooks they produced are colorful, engaging and focused on issues relevant to adolescents, such as applying for a job for the first time or saving money for the traditional end-of-year trip with classmates. A page out of one of the books, focused on budgeting is shown below. In addition to an investment in materials, the program included teacher training and outreach to parents. This program was rigorously evaluated with help from the World Bank, and it was found to increase the financial autonomy of students as well as savings rates.

While these results are promising, they are not necessarily easily replicable. Classroom instruction is also the highest-cost way to deliver financial education, and it is thus the most difficult approach to scale up. By incorporating financial issues in other curricula such as math or history (as was done in Brazil), the costs may be lowered, at least for schools.

One final issue from the dataset of financial-education interventions – a finding that is likely to affect results – is the short timeframe for most interventions. Only 8 percent of the studies were of interventions lasting more than 20 hours. Twice as many of the interventions that were studied (16 percent) lasted no more than two hours, and 38 percent of the sample consisted of interventions lasting 10 hours or less. This may simply be too little time for sustained knowledge gains and behavior change to occur in most circumstances. (Almost half of the papers did not clearly indicate the number of hours of instruction and thus were coded as “varied.”)

So when it comes to designing and implementing programs to promote financial literacy and financial capability, there’s a great deal that we still don’t know. Given the importance of financial education in helping expand financial inclusion – a key priority, as this year’s GFDR points out, in the quest to build shared prosperity – there is clearly a need for additional research. The cause of financial inclusion is too important, and the cost of financial illiteracy is too great, to use hit-or-miss experiments rather than methods that are proven by rigorous analysis to deliver effective results.

A paper by Miller, Reichelstein, Salas and Zia 2013, entitled “Can You Help Someone Become Financially Capable?” ( http://www.worldbank.org/financialdevelopment), undertakes a systematic review of the literature on financial education interventions of all types, which includes the use of “meta-analysis” to compare and evaluate the results. They identify 188 papers that present findings on a variety of interventions – the most rigorous and comprehensive evaluation of this literature to date.

Using a meta-analysis is useful in this case, because it is a methodology that facilitates a statistically rigorous comparison of data across independent studies. By pooling data across studies, research findings that may individually point to inconclusive or contradictory results may together yield a statistically significant finding.

In researching financial literacy and capability interventions, meta-analysis can help compare a variety of contradictory and sometimes inconclusive results. However, there are limits to the insights that can be drawn using meta-analysis with a highly diverse literature.objective of the program intervention, the intensity and duration of the intervention, the delivery channels used and the target population.

To make comparisons easier using meta-analysis, and to overcome (at least to some extent) the difficulties posed by the diverse nature of the results, studies were grouped according to the issue they addressed and according to similar outcome (dependent) variables. The most common single-issue topic for financial education interventions was savings and retirement, and the greatest number of comparable papers also address this issue.

The “forest plot” (below) provides observations from six research papers that address the impact of financial education interventions on savings, using a binary dependent variable for increases in savings. A forest plot graphically displays the treatment effects across multiple studies, with a solid line representing the null hypothesis of no effect from the intervention – in this case, from exposure to financial education outreach and training.

In this particular meta-analysis, three of the six papers reject the null hypothesis – that is, they indicate a positive impact on savings from financial education – while the three other papers cannot reject the null hypothesis. Taken together, however, the meta-analysis finds that these papers do provide evidence of impact for financial education. The confidence interval for the pooled data across the six papers is represented by the diamond at the bottom of the graph. It is clearly on the right-hand side of the null hypothesis, rejecting a finding that financial education has no impact on savings behavior. At the same time, the impact appears to be fairly small in magnitude. We lack, however, the data on means and standard deviations to determine the true effect size for this finding, because each study is based on a different level of initial savings, in both absolute terms and relative to income.

My co-authors and I also review the impact of financial education on retirement savings, loan defaults and financial recordkeeping. We cannot rule out the null hypothesis of no impact from the financial-education intervention, either in the case of retirement savings or loan defaults – but they do find an impact on recordkeeping behaviors.

What are some of the reasons for the apparently limited impact from financial-education interventions to date? The World Bank’s 2014 Global Financial Development Report (GFDR) cites several factors that can determine the effectiveness of financial education and outreach – but those factors are in short supply in the studies in the database. These include an attention not only to the information being provided, but also to the way content is delivered. They take into account insights from psychology that may be important for knowledge gains and behavior change.

For example: The delivery channel matters. More entertaining, interactive approaches to teaching financial education are more likely to “stick” than passive outreach, such as brochures or lectures that don’t capture participants’ attention. In fact, there is a growing body of evidence of the importance of storytelling – through books, video or other media – for effective education and outreach ( http://jonathangottschall.com/about-the-book/). One such paper, Berg and Zia 2013 ( http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/1813-9450-6407), discusses the impact that occurred from the inclusion of financial messages in a South African soap opera: “Scandal.” Using a rigorous evaluation, the study shows that viewers of “Scandal” improved their financial knowledge and were less likely, after viewing the show, to engage in risky activities (such as gambling and using costly hire-purchase agreements) than were non-viewers.

However, among the 188 studies in more than half of the cases, the interventions are taught by an instructor in a classroom setting. Other channels used to deliver the content – such as mass media, online tools, individual counseling, phone or print – are all below 10 percent in the sample. A relatively small share of the studies (18 percent) reports using more than one delivery mechanism, although this is considered a good practice by communication and education professionals.

With a good instructor, and with attention to the psychological determinants of financial behavior, however, a classroom approach can be effective. This is the lesson from Bruhn and others (Powerpoint available on http://www.finlitedu.org ) from a forthcoming study of a three-semester financial-education program developed for Brazilian high schools. Program designers included professionals in psychology, and they sought input from students as they developed the materials. The workbooks they produced are colorful, engaging and focused on issues relevant to adolescents, such as applying for a job for the first time or saving money for the traditional end-of-year trip with classmates. A page out of one of the books, focused on budgeting is shown below. In addition to an investment in materials, the program included teacher training and outreach to parents. This program was rigorously evaluated with help from the World Bank, and it was found to increase the financial autonomy of students as well as savings rates.

While these results are promising, they are not necessarily easily replicable. Classroom instruction is also the highest-cost way to deliver financial education, and it is thus the most difficult approach to scale up. By incorporating financial issues in other curricula such as math or history (as was done in Brazil), the costs may be lowered, at least for schools.

One final issue from the dataset of financial-education interventions – a finding that is likely to affect results – is the short timeframe for most interventions. Only 8 percent of the studies were of interventions lasting more than 20 hours. Twice as many of the interventions that were studied (16 percent) lasted no more than two hours, and 38 percent of the sample consisted of interventions lasting 10 hours or less. This may simply be too little time for sustained knowledge gains and behavior change to occur in most circumstances. (Almost half of the papers did not clearly indicate the number of hours of instruction and thus were coded as “varied.”)

So when it comes to designing and implementing programs to promote financial literacy and financial capability, there’s a great deal that we still don’t know. Given the importance of financial education in helping expand financial inclusion – a key priority, as this year’s GFDR points out, in the quest to build shared prosperity – there is clearly a need for additional research. The cause of financial inclusion is too important, and the cost of financial illiteracy is too great, to use hit-or-miss experiments rather than methods that are proven by rigorous analysis to deliver effective results.

Join the Conversation