Nyani Quarmyne (Panos)/ IFC

Nyani Quarmyne (Panos)/ IFC

Global Value Chains (GVCs) have boosted productivity growth and structural transformation in many developing countries, by allowing them to specialize in certain activities and stages of production rather than waiting for entire industries to develop. GVCs encompass a myriad of firm-to-firm relationships through investment, trade, people, technology, and information flows.

GVCs benefit from policy makers’ capacity to create a conducive environment for attracting foreign direct investment (FDI), help domestic firms internationalize, and facilitate the interactions between multinational corporations (MNCs) and domestic firms. Our new report An investment perspective on GVCs provides insights on the topic, with a focus on three key players that shape GVCs: MNCs, domestic firms, and policy makers. It analyzes GVCs from a FDI perspective and investigates the role of FDI in countries’ GVC integration and upgrading. The report also touches on how COVID-19 has affected GVCs, building on a previous series of blogs.

Multinational corporations drive GVC expansion

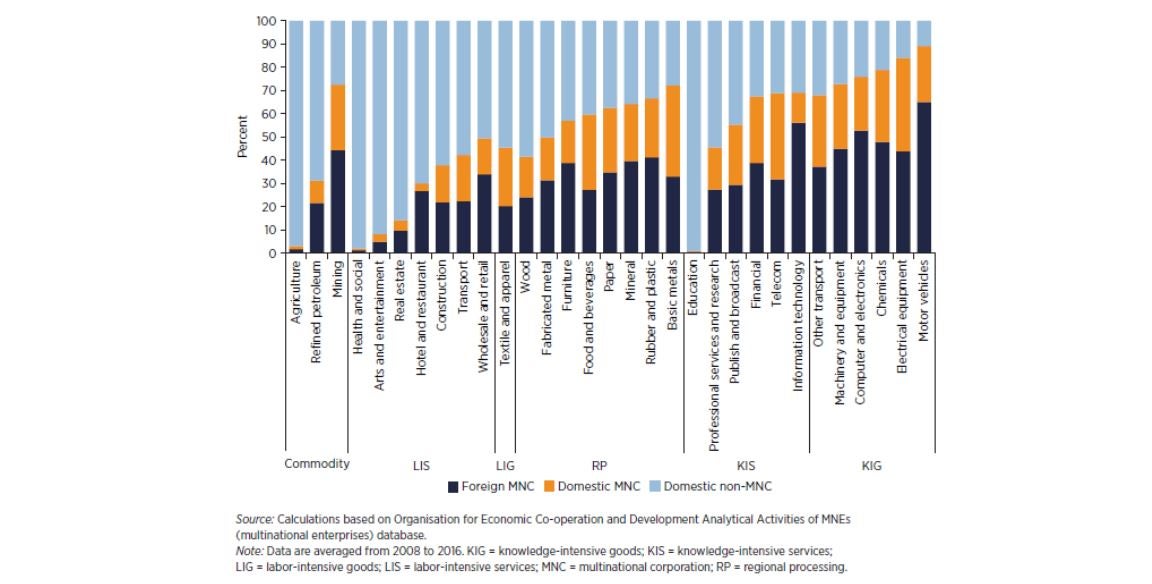

MNCs account for a significant share of global output and trade in most sectors. Multinational corporations and their affiliates accounted for 36 percent of global output in 2016, making up about two-thirds of global exports and more than half of imports , according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s AMNE Database—Activity of Multinational Enterprises. Their contribution is especially pronounced in knowledge-intensive goods sectors, where MNCs make up as much as 90 percent of exports (Figure 1).

Benefits for domestic companies

But despite the importance of MNCs, domestic firms play an indispensable role in international production networks. For example, in the United States, a typical MNC buy 25 percent of inputs from more than 6,000 small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Similarly, Japanese MNCs based in Southeast Asia source more than half of their inputs from local firms. Domestic firms participate in GVCs through four main pathways: supplier linkages in a GVC network, strategic alliances with MNCs, direct exporting, and outward FDI. These pathways are not mutually exclusive and can build on each other.

Domestic firms can be more integrated to GVCs by increasing their interactions with MNCs and by continuing to learn from them. This way, domestic firms can obtain the necessary production capabilities and foreign market knowledge to directly compete in international markets.

Increased interactions with multinational corporations raise a company’s probability of becoming an exporter. (Figure 2) It also strengthens firms’ ability to produce more, higher-quality, or more complex products, and in turn improve overall firm performance. An event study of MNC suppliers in Costa Rica found that four years after becoming a supplier to an MNC, local firms saw a 20 percent increase in sales, a 26 percent expansion in employees, and a 9 percent growth in productivity. An empirical case study in India, which is also part of this report, shows that local companies in joint ventures with MNCs are 30 percent more likely to export directly than local companies with no interaction.

Different approaches for leveraging FDI

Governments have often played key roles in promoting GVC participation in the past decades. They improve their countries’ overall competitiveness through macroeconomic policies, infrastructure building, enabling regulatory environment, and human capital development. These constitute a set of necessary minimum conditions for any country to be considered attractive investment destinations. In addition, some governments have applied “light-handed” industrial policies to solve specific sectors’ market failures caused by externalities, imperfect information, and coordination problems.

This report features five case studies that showcase the various approaches developing countries have taken to use FDI to stimulate GVC participation and upgrading (Figure 3).

- In Kenya, MNCs contracted local farmers to supply them with fruits, vegetables, and flowers, and trained local farmers to meet global standards. Half of such farmers became direct exporters after becoming suppliers to MNCs.

- In Honduras, the government set up special economic zones and signed international trade and investment agreements. This attracted foreign investors in apparel industry, which now accounts for 40 percent of the country’s exports.

- In Malaysia, the government proactively targeted “superstar” firms and offered them investment incentives. These superstar firms jointly jump-started Malaysia’s electronics industry, now making up half of the country’s exports.

- In Mauritius, the government stimulated local tourism companies to partner with MNCs. This helped double the number of new tourists in Mauritius and triple tourism revenue.

- In the Republic of Korea, India, and China, the government stimulated leading domestic ICT firms to invest overseas, which helped them acquire new technology, explore new markets, and compete internationally. Currently, 15 out of the top 100 ICT multinationals are from these countries.

It is our hope that the theories, latest evidence, and practical examples brought together in this new report will inspire policy makers around the world to accelerate economic recovery, create productive jobs, and achieve GVC upgrading by attracting FDI and helping domestic firms internationalize.

Join the Conversation