Helen Mwangi and her solar-powered water pump in Kenya © infoDev/World Bank

Managers of initiatives that support innovative entrepreneurs have a choice to spread their resources (and luck) among many opportunities or focus them on the most promising few. In developing countries, public and donor programs can learn a lot from how private investors pick and back innovative ventures.

In the early days of infoDev’s Climate Technology Program, our thinking was very much about letting a hundred flowers bloom: supporting a large number of firms with the hope that a few would emerge as blockbusters. Firms were selected on the basis of objective metrics tied to the innovative nature of their ideas and their economic, social and climate-change impacts. For example, while infoDev’s partner the Kenya Climate Innovation Center has more than 130 companies in its portfolio, a $50 million venture-capital fund in California would have at most six. Inspired by private investors, we have since rethought our program objectives for these centers, as well as the way we select and support businesses. The Kenya center is going through a rationalization of the firms it supports.

Like many public programs, infoDev and its network of Climate Innovation Centers had good reasons to support large numbers of companies. The main reason is the need to spread the entrepreneurship risk through a diversified portfolio. A recent infoDev literature review found that up to a third of all new firms do not survive beyond two years, let alone grow. Out of those that survive, data from high-income countries suggest that fewer than 10 percent become high-growth firms. So casting a wide net increases the chances of hitting the jackpot. The opposite approach, picking winners, is seen as destined to fail and distort the market.

Another reason public and non-profit programs, particularly those with a development lens, tend to support more businesses is that this helps generate large output figures. Outputs are results that can be directly attributed to the program. Examples might include “X numbers of businesses supported” or “Y amount of funds invested.” Outcomes of innovation, on the other hand, are results that are further down the road and help to answer the fundamental question of why a program was created. Examples of outcomes might include “number of products sold” or “number of jobs created by the businesses supported.” Outcomes of innovation are only visible after many years, and sometimes difficult to account for, so innovation programs tend to be measured by their outputs.

As a result, public programs run into the risk of diluting limited resources across large numbers of entrepreneurs. The question is whether there might be a critical mass of support resources below which a program has no effect on the entrepreneur’s performance. The evidence suggests that for run-of-the-mill businesses, limited training and some cash can go a long way. For example, a World Bank working paper that evaluated a business-plan competition including 1,200 businesses in Nigeria found that four days of training and an average $50,000 award increased prospects for survival and likelihood of a firm growing to more than 10 workers.

Our hypothesis is that this does not translate to businesses with high growth aspirations. In the world of high-growth firms, angel investors and venture capitalists invest in very few businesses because they provide them with a lot of money and significant hand-holding and networking support. Moreover, they ensure that they can add value to the business by investing in sectors or product markets with which they are intimately familiar.

And it’s not only about stretching resources thin, it’s also about stretching competencies. In many developing countries where infoDev works, small and growing businesses with talented teams are few and far between, particularly in climate technology sectors. Talented individuals tend to work in traditional sectors and larger organizations. That means that backing a large portfolio of businesses requires admitting entrepreneurs with varying levels of skills, experience and growth aspirations. The problem is that each of these groups of entrepreneurs needs very different forms of support. Inexperienced entrepreneurs will need to learn how to write business plans, mature entrepreneurs will need to focus on management systems, and growing businesses will need investment readiness. It is difficult for a small public or donor program to develop skills and a competitive advantage in each of these market segments and become all things to all entrepreneurs.

In Ethiopia, infoDev is working with its network partner, the Ethiopia Climate Innovation Center (ECIC), to reduce its scope from all climate change-related sectors to a limited number of product markets, starting with off-grid household solar. The ECIC will focus on supporting firms that are ready to undergo expansion and reach scale. As a result, it will prioritize nine out of the 60 businesses it currently supports. Instead of light-touch mentoring and small grants, the prioritized businesses will receive deeper support tailored to their markets and to their growth stage, help accessing more important sources of finance, and help addressing challenges in their business environment. We expect this change to result into more success stories of high-impact businesses.

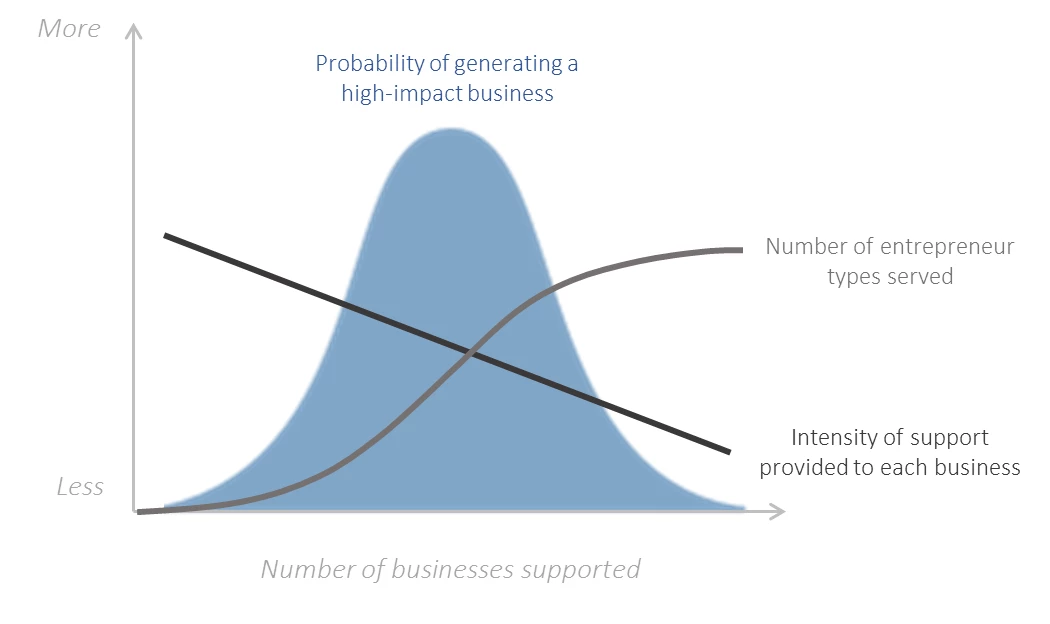

The above figure summarizes the trade-offs of supporting too many businesses. It increases the number of types of entrepreneurs, which leads to less specialized support, and it lowers the intensity of support, which reduces the ability to help high-impact entrepreneurs overcome market gaps. Letting a hundred flowers bloom can be an appropriate strategy where a program is aiming to create jobs or increase productivity in moderate-growth, profit-positive businesses. It can also play a role in raising awareness among entrepreneurs and consumers alike in a sector. Where a program objective is to help generate high-impact or transformational businesses, a more targeted approach is needed. This requires an authorizing environment for the risk-taking that is needed, and the acceptance of a failure as a possibility. But it should be failure with learning and iteration!

Join the Conversation