COVID-19 has accelerated demand for digital financial services (DFS) and fintech technology—and in doing so it has concentrated the minds of policymakers and financial regulators everywhere. Technological innovation, after all, tends to outpace regulatory change. That can prompt market participants to shop around for jurisdictions with weaker rules.

Not surprisingly, regulators are racing to plug the gaps. A variety of legislative initiatives loom over the fintech landscape. They cover everything from data privacy and consumer protection to digital-only banks. Knowing exactly how these initiatives are being designed can enable policymakers, researchers, and development organizations to identify, compare, and contrast the merits of each.

That’s why the World Bank Group assembled its Global Database of Fintech Regulations. This new database constitutes a curated library of enabling laws, regulations, and guidelines from nearly 200 countries—all in a searchable and easy-to-use format.

This database sheds important light on some of the causes of the global digital divide. Some countries have strong enabling regulations for fintech and digital financial services. Others simply lack the necessary regulatory infrastructure. The database provides useful insights into the basic legal and regulatory requirements for creating a vibrant fintech ecosystem.

Foundational requirements for Fintech

First, a definition is in order. The World Bank and the IMF use the term “fintech” to describe “advances in technology that have the potential to transform the provision of financial services spurring the development of new business models, applications, processes, and products.” Smart phones, for example, have been transformative in this regard: they have enabled millions of people across the world to carry out financial transactions instantaneously—without ever having to step into a bank branch. But fintech today also leverages newer innovations such as distributed ledger technology and artificial intelligence.

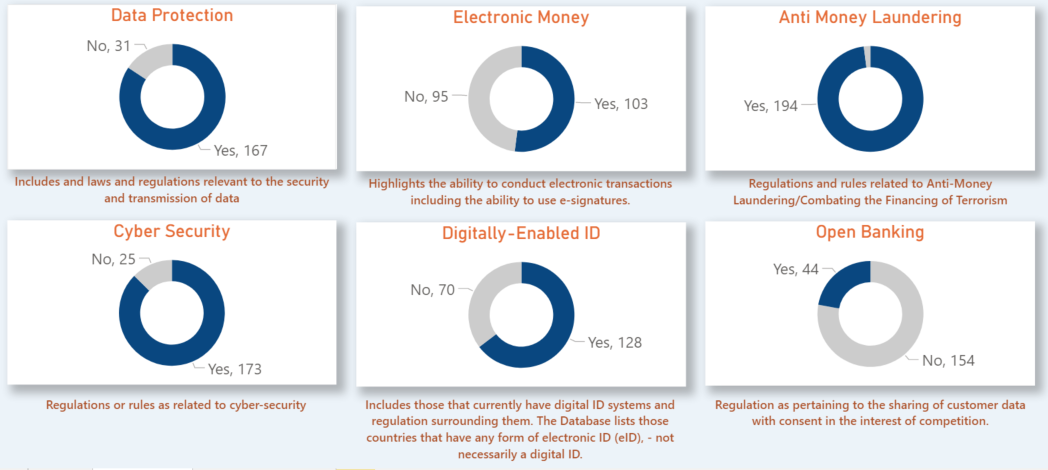

To effectively support innovation in the industry, a first step should be to put in place the foundational legislation—along with guiding principles on how they should apply to emerging areas such as distributed-ledger technologies or cloud computing. Such legislation should cover data protection and cybersecurity, the ability to conduct electronic transactions, and Electronic Know Your Customer (eKYC) processes, among other things.

Our data show that foundational legislation exists in most countries. Yet there are important gaps. For example, some countries in East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean have yet to implement the basic data-protection regulations necessary for fintech to take root. Moreover, the definition and interpretation of personal information is often inconsistent in data regulations across jurisdictions.

Figure 1: Coverage of Foundational Legislation around the World

Measures related to digital signatures are also necessary regulations. Such signatures involve an electronic, encrypted stamp of authentication on digital information. When backed by appropriate regulations, they can offer a high level of security in payments—along with speed and increased efficiency.

Digital ID regulations are equally important. Digital IDs—when implemented appropriately—can streamline Customer Due Diligence (CDD) requirements, lowering the cost for fintech providers without compromising safety and integrity. One key benefit of digital IDs is their ability to contain static information such as age, name, and gender while also maintaining a digital trail of dynamic information about the individual. Our database lists countries that have any form of electronic ID (eID)—not necessarily a ‘digital ID’.

Treatment of Fintech products

Many fintech products today are covered by existing regulation under the principle of ‘same activity, same treatment.’ Nevertheless, fintech-specific regulation has been developed in some cases.

For instance, in the case of digital banking, our data shows that most jurisdictions apply existing banking laws and regulations to banks within their remit, regardless of the technology they adopt or the presence (or absence) of branches. However, certain jurisdictions—such as Hong Kong, Singapore, and the Philippines—have separate license arrangements for digital-only banks. Others, such as the UK and Australia, chose a middle ground—one that involves transitional arrangements and restricted licensing in the initial phase.

The treatment of cryptocurrencies warrants closer attention. Although legislation has been introduced by some countries, most have only released guidelines but not gone on to incorporate them into law. El Salvador is the first country that has chosen to make cryptocurrency a legal tender. More commonly however, countries have merely issued warnings to consumers on the volatility of cryptocurrencies. The potential risks of cryptocurrencies with respect to money-laundering and the financing of terrorism remain a key concern for policymakers—along with how cryptocurrencies should be treated for tax purposes.

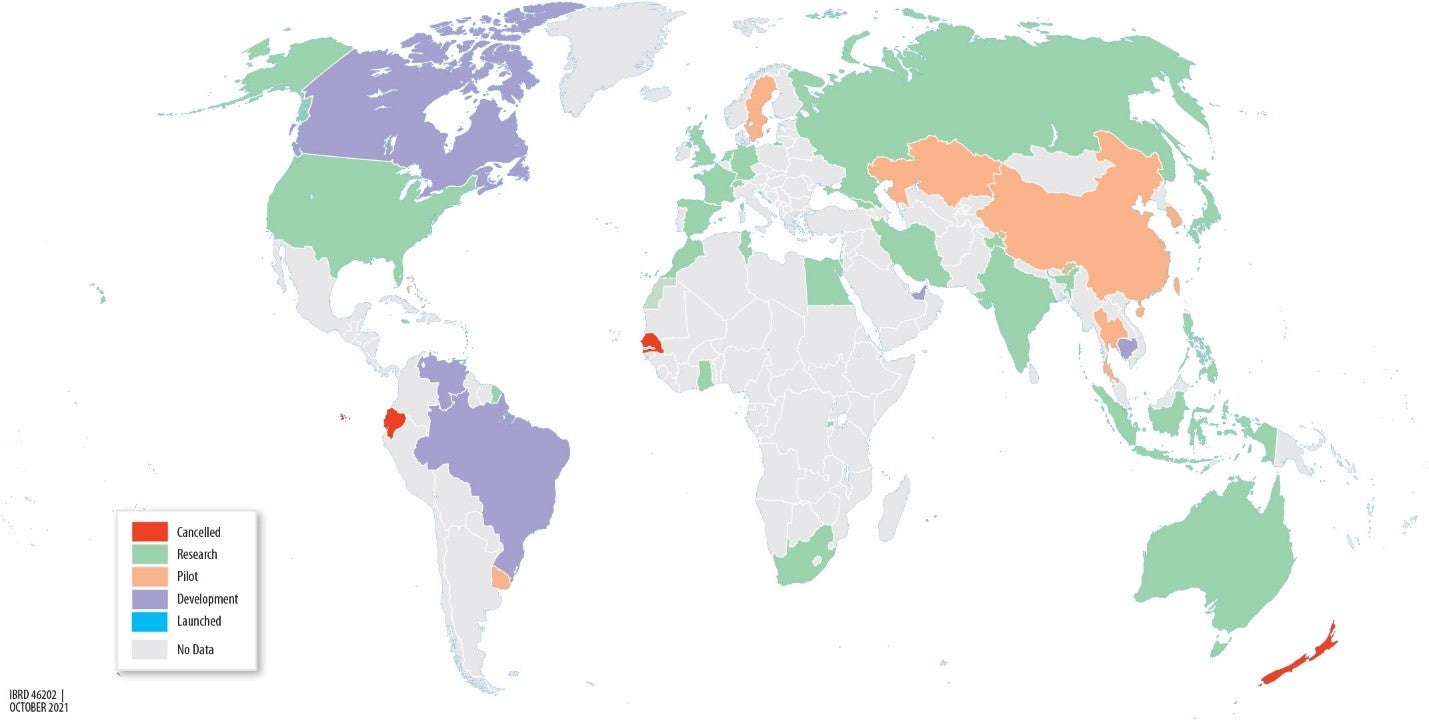

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) are also a subject of interest in many jurisdictions. Bahamas so far the only country that has formally launched such a currency, but others such as China are not far behind.

Figure 2: CBDC around the world

Responsible progress in the fintech sector will depend on appropriate regulation—which always requires careful calibration.

In assessing whether their regulatory framework is adequate or needs to be adjusted, financial authorities will need to weigh multiple elements. Some jurisdictions have adopted the use of innovation facilitators, such as “sandboxes,” to support the fintech sector and help them analyze market trends. But whatever path they take, authorities will need to balance the potential benefits for society—faster financial development and greater inclusion—against the potential risks to financial stability and market integrity and to the welfare of consumers and investors.

Join the Conversation