One of the most destructive effects of the global financial crisis on many countries has been a rise in unemployment. To address this, policy makers everywhere are putting a great deal of energy into devising policies that will increase the proportion of their adult population in jobs. With the publication of Women, Business and Law data, which was updated in 2011, we have fresh insight into one particular issue of employment: encouraging female labour force participation.

Ensuring that women can take part in the workforce on equal terms with men is important for gender equality and poverty reduction. When women can work they are able to provide for themselves and their families. What’s more, the female labour force participation rate in a country is linked to its GDP and international competitiveness (WEF 2010). Yet in all but one country (Rwanda), women significantly lag behind men in the work force.

The numbers paint a dismal picture of the global employment gap between men and women. On average, for every 100 men who participate in the labour force, only 72 women do. The bottom quarter of countries all have only 62 or fewer women to every 100 men in the labour force. This is bad across the economic spectrum: even in countries ranked as high income by the World Bank, the figure is 76.

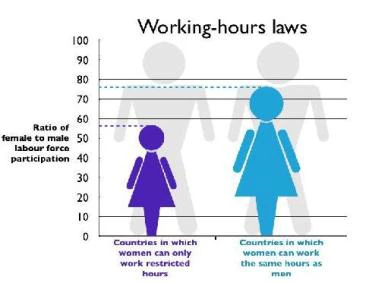

So what can countries do to increase women’s labour force participation? My analysis reveals some answers that are intuitive: In countries where women are allowed to work in all the same industries as men, women’s labour force participation is higher on average1. Meanwhile, in countries where there are restrictions on the hours women can work, women’s labour force participation is lower. Many of these measures are intended to be protective: some countries ban women from working at night because it is considered dangerous for women to commute to jobs at night-time (WBL 2010). But these laws may be damaging to women’s ability to participate in the labour force and provide for themselves or their families.

One of the most interesting stories the data tells is around maternity leave. Both common sense and many studies attest to the fact that it is easier for women to balance family and work commitments when they can take some time off after having a baby. So maternity leave increases women’s ability to participate in the labour force. But there is a trade-off: overly-generous maternity leave makes employers think twice before hiring women in the first place.

This was very clear when I looked at the impact of longer and shorter maternity leave policies. WBL shows that 102 of the 128 countries surveyed mandate at least the 14 weeks of maternity leave advised by the International Labour Organisation. The mean ratio of female to male labour force participation for countries that mandate at least 14 weeks of maternity leave is 77.3% compared to 65.3% for countries that don’t (significant at the 0.01 level). It looks like the longer the maternity leave, the smaller the gap between men and women. But this trend reverses at the 140 day mark: very lengthy leave actually hinders women’s labour force participation. Such policies may discourage employers from hiring women in the first place. On top of this, extended absence from the workforce for maternity leave may hinder women’s labour market skills, and damage future career paths and earnings.

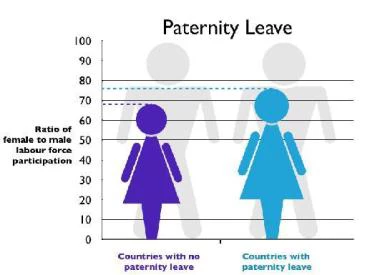

If maternity leave makes women less attractive to employers, this can at least be partially balanced by the provision of paternity leave. Once both women and men have the right to take time off after the birth of their child, women are less of a risk in the eyes of employers. WBL shows a significant and substantial difference in the average gender ratio of labour force participation between economies that mandate paternity leave and those that don’t.

A multitude of non-policy factors undoubtedly influence female labour force participation, such as cultural expectations and the type of industry in which a country specializes. Nonetheless, analysis of the Women, Business and Law database reveals broad trends that can be useful for policy makers in understanding how to encourage women in the workforce.

Here – as everywhere – this means the ratio of female labour force participation to male labour force participation. I have chosen to use the ratio, rather than straight figures of female labour force participation, because the important point is how legislation affects women relative to men in the workforce. This metric minimizes irrelevant differences between countries due to biases from different ways of collecting the data, as well as different unemployment rates or sizes of the informal as opposed to formal economy.

All views expressed here are the author's own, and this paper was written while she was still a student at Harvard University.

1 Here – as everywhere – this means the ratio of female labour force participation to male labour force participation. I have chosen to use the ratio, rather than straight figures of female labour force participation, because the important point is how legislation affects women relative to men in the workforce. This metric minimizes irrelevant differences between countries due to biases from different ways of collecting the data, as well as different unemployment rates or sizes of the informal as opposed to formal economy.

Join the Conversation