As we celebrate Women’s History Month this March, we must continue to push the envelope on operationalizing gender parity for our clients. In developing contexts, women are often concentrated in informal work, micro and small enterprises, or employed in the lower ends of the value chain in primary agriculture, light manufacturing, and tourism industries. A prime country example illustrating this trend is Bangladesh, where female labor force participation hovers around 57% and the

ILO reports that 80-85% of labor in the booming ready-made garments industry is provided by women.

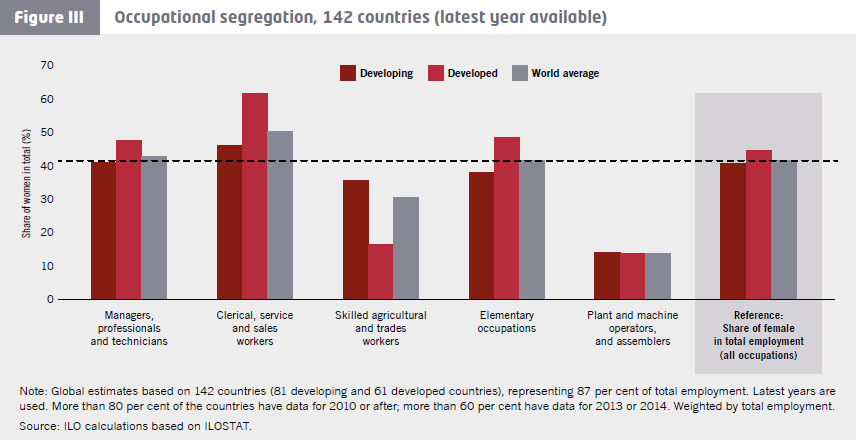

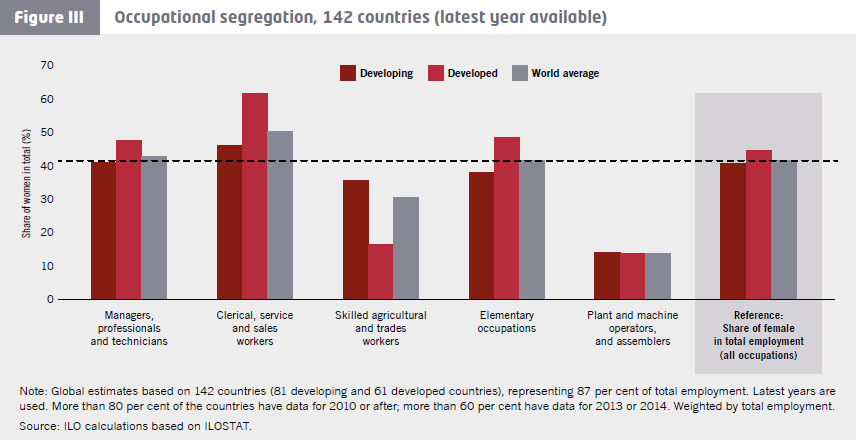

Differences in Average Shares of Major Occupational Groups by Sex in Selected Economies

Source: ILO, Women at Work: Trends, 2016

Source: ILO, Women at Work: Trends, 2016

As economies seek to become more and more competitive, the question remains: how do we make sure that these benefits accrue equally to both sexes and that women are not left behind? And, once foreign direct investment-led diversification is cultivated, how do we absorb women who were traditionally excluded into new, high-growth careers and sectors?

One way to ramp up the benefits to women as economies diversify is to examine how behavioral investment incentives can promote female leadership, entrepreneurship and labor market participation in client countries. Trade and Competitiveness’ ongoing research on investment incentives targeting women at work explores these solutions with practical insight.

Incentives such as in-kind grants, wage subsidies, direct payments to firms for hiring women workers, and credit subsidies for women-owned firms can encourage women who might otherwise not enter the workforce, new sectors, or start their own businesses. Tax credits and subsidies incentivizing the provision of childcare, parental leave and training by firms, can also be used to indirectly target gender equality goals.

Source: Kronfol, Nichols, and Tran. “Women at Work: Investment Incentives Targeting Gender Equality in the Workforce, [Working Title], World Bank Group, Forthcoming 2017.

Source: Kronfol, Nichols, and Tran. “Women at Work: Investment Incentives Targeting Gender Equality in the Workforce, [Working Title], World Bank Group, Forthcoming 2017.

In Jordan, where only 17% of women ages 20-45 work (compared to 77% of men), a pilot program used short-term wage subsidies to increase female employment. Although 93% of female graduates report wanting to work after graduation, they lack professional networks and employers have little exposure to women employees. To address this challenge, the Jordan New Opportunities for Women (Jordan NOW) program gave women job vouchers which paid employers a subsidy of up to six months of the minimum wage if the women were hired. The vouchers were intended to boost the confidence of graduates to approach employers. At the same time, the scheme allowed employers to observe the women’s capabilities prior to formally hiring them and offset any perceived or real costs of doing so.

India offers a number of credit subsidy programs to promote female entrepreneurship. The programs are financed through banks and subsidized by the government. For example, the Trade-Related Entrepreneurship Assistance and Development (TREAD) Scheme, is subsidized by the Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises and provides a subsidy of up to 30% of total project cost. Lending institutions then finance the remaining 70%. The program targets marginalized women who struggle with access to credit because they lack collateral, are low-income and illiterate or semi-literate. NGOs address the literacy challenges by helping women file their subsidy requests.

Without these incentives and left to market conditions, the women in both Jordan and India would be unfairly disadvantaged due to systemic barriers. However, incentives can, at best, only be a partial solution. In the case of the Jordan NOW program, results showed that the job vouchers led to a 40 percentage point increase in female employment in the short-run, but the effects waned and lost significance down the line.

Non-incentives policies and solutions, however, are still important tools needed in tandem. Governments should carefully consider the combination of incentives and other policy tools, including regulations, information and facilitation, and reform of tax codes, that will be most effective at overcoming barriers to gender equality and targeting policy goals.

The complex dance that women around the world engage in to balance home and work cannot be overstated. And no one tool can serve as a panacea to end the time poverty, social, legal and cultural barriers that women face. In addition, incentives schemes are not one-size fits all. The effectiveness of incentives depend on how well suited they are to the underlying barrier to gender equality and to targeted policy goals. In addition, the use of incentives to target gender equality is a new and evolving field. Lessons are still being learned on their effectiveness, particularly in the developing world.

Differences in Average Shares of Major Occupational Groups by Sex in Selected Economies

As economies seek to become more and more competitive, the question remains: how do we make sure that these benefits accrue equally to both sexes and that women are not left behind? And, once foreign direct investment-led diversification is cultivated, how do we absorb women who were traditionally excluded into new, high-growth careers and sectors?

One way to ramp up the benefits to women as economies diversify is to examine how behavioral investment incentives can promote female leadership, entrepreneurship and labor market participation in client countries. Trade and Competitiveness’ ongoing research on investment incentives targeting women at work explores these solutions with practical insight.

Incentives such as in-kind grants, wage subsidies, direct payments to firms for hiring women workers, and credit subsidies for women-owned firms can encourage women who might otherwise not enter the workforce, new sectors, or start their own businesses. Tax credits and subsidies incentivizing the provision of childcare, parental leave and training by firms, can also be used to indirectly target gender equality goals.

In Jordan, where only 17% of women ages 20-45 work (compared to 77% of men), a pilot program used short-term wage subsidies to increase female employment. Although 93% of female graduates report wanting to work after graduation, they lack professional networks and employers have little exposure to women employees. To address this challenge, the Jordan New Opportunities for Women (Jordan NOW) program gave women job vouchers which paid employers a subsidy of up to six months of the minimum wage if the women were hired. The vouchers were intended to boost the confidence of graduates to approach employers. At the same time, the scheme allowed employers to observe the women’s capabilities prior to formally hiring them and offset any perceived or real costs of doing so.

India offers a number of credit subsidy programs to promote female entrepreneurship. The programs are financed through banks and subsidized by the government. For example, the Trade-Related Entrepreneurship Assistance and Development (TREAD) Scheme, is subsidized by the Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises and provides a subsidy of up to 30% of total project cost. Lending institutions then finance the remaining 70%. The program targets marginalized women who struggle with access to credit because they lack collateral, are low-income and illiterate or semi-literate. NGOs address the literacy challenges by helping women file their subsidy requests.

Without these incentives and left to market conditions, the women in both Jordan and India would be unfairly disadvantaged due to systemic barriers. However, incentives can, at best, only be a partial solution. In the case of the Jordan NOW program, results showed that the job vouchers led to a 40 percentage point increase in female employment in the short-run, but the effects waned and lost significance down the line.

Non-incentives policies and solutions, however, are still important tools needed in tandem. Governments should carefully consider the combination of incentives and other policy tools, including regulations, information and facilitation, and reform of tax codes, that will be most effective at overcoming barriers to gender equality and targeting policy goals.

The complex dance that women around the world engage in to balance home and work cannot be overstated. And no one tool can serve as a panacea to end the time poverty, social, legal and cultural barriers that women face. In addition, incentives schemes are not one-size fits all. The effectiveness of incentives depend on how well suited they are to the underlying barrier to gender equality and to targeted policy goals. In addition, the use of incentives to target gender equality is a new and evolving field. Lessons are still being learned on their effectiveness, particularly in the developing world.

Join the Conversation