Booking travel online concept

Booking travel online concept

For over a century, manufacturing-led growth—powered by efficiency gains from operating at greater scale, from innovation based on combining labor with capital, and from positive spillovers to other sectors—has been the focus of efforts to foster economic development and poverty reduction. Conventional wisdom has been pessimistic about the prospects for services-led development because such opportunities were few and far between in the services sector. This thinking needs to change. In our book, At Your Service?: The Promise of Services-Led Development, we show that the acceleration of digitization has created new opportunities for scale, innovation, and spillovers. This is spurring the “industrialization” of services and increasingly driving economic growth in developing countries.

Scale economies

Scale in the manufacturing sector typically derived from access to large international markets. In contrast, the need for physical proximity between producers and consumers constrained trade in most services. Restaurant meals, banking transactions, and surgeries tended to happen in person. Since the 1990s, the information technology revolution has enabled the offshoring of modern services, such as software programming, call centers and business process outsourcing (BPO) to lower-cost destinations, much like global value chains did for manufactured goods. This enabled scale through access to larger markets. For example, professional, scientific, and technical services grew to around 20 percent of the Philippines’ total exports by 2017 and was the second-largest contributor to the country’s foreign-exchange earnings. The rapid expansion of bandwidth and new digital platforms have also given rise to a new form of online freelancing for professional services. Two-thirds of freelancers exporting their services on English-speaking online labor platforms, such as Upwork, Freelancer, Fiver, and Thumbtack, are based in developing economies.

Digitalization is creating new opportunities for scaling up among traditional services too. For example, streaming platforms such as Netflix and YouTube are fast enabling providers of arts, entertainment, and recreation services to export their creative content at low cost. Where in-person delivery remains important, such as in restaurants as well as retail stores, the standardization of production over many establishments—itself enabled by data analytics and digitally connected management systems—has enabled firms to scale up across multiple locations near consumers.

Innovation

The accumulation of physical capital in the form of production-related machinery and equipment played a much smaller role in the growth of services firms than in manufacturing. For example, giving hairdressers more pairs of scissors will not enable them to provide more haircuts, and the quality of the haircut depends overwhelmingly on the skill of the person cutting the hair. However, the accumulation of information and communications technology (ICT) capital—computer hardware and software—has enhanced labor-augmenting innovation in the services sector. The diffusion of digital technologies has gone hand-in-hand with a rise in forms of intangible capital, such as database assets, innovative properties such as R&D and design , as well as company competencies such as branding, organizational practices, and business process engineering. Across all sectors, the share of ICT-related tangible and intangible investments is the highest among modern ICT and professional services. At the same time, the intensity of such capital accumulation is also higher in several traditional services relative to the industrial sector (figure 1).

Figure 1: Share of tangible and intangible capital in investment, United States, 2015

This combination of labor with ICT-related capital is bringing innovation. Travel apps for hospitality services, such as Booking, Expedia, and MakeMyTrip, have reduced the need for physical proximity in matching demand and supply. Mobile apps that facilitate inventory management and accounting are enabling small retailers to make their internal business processes more efficient. Ridesharing apps such as Uber, Ola, and Grab are also substituting for missing skills. For example, Uber drivers do not need extensive geographical knowledge of the area where they drive (because the app can navigate them) or numeracy skills (because all payments are done through credit cards on the platform). Intangible capital accumulation owing to digitization will only intensify as the uptake of AI-enabled image recognition, voice recognition, and machine translation are applied to non-routine (manual and cognitive) tasks that are more prevalent in the services sector.

Spillovers

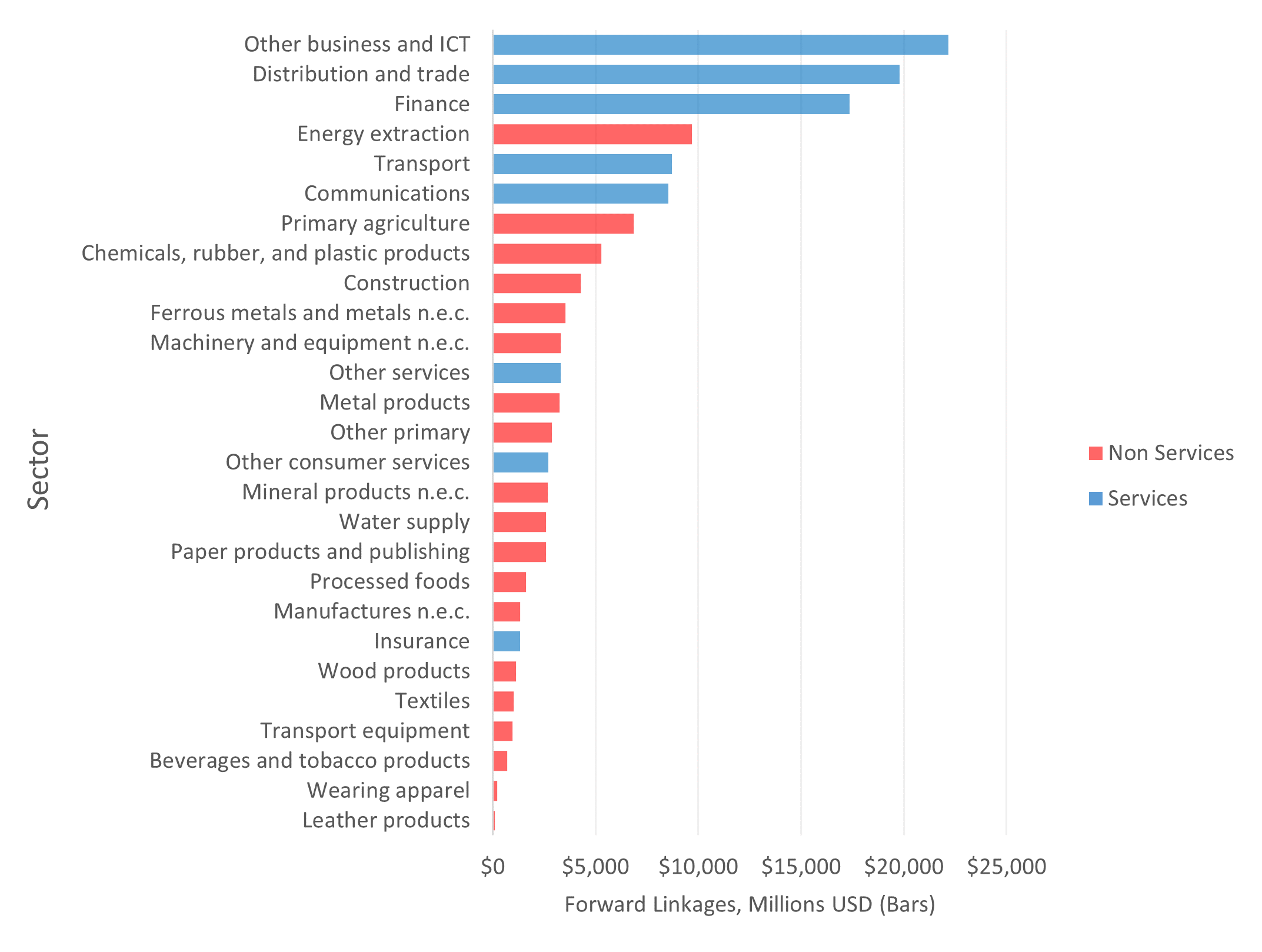

Services are important inputs in economywide production. The value of these forward linkages is highest for ICT and professional services, followed by distribution, finance, communication, and transportation services—which are ahead of all manufacturing subsectors (figure 2). The role of services as upstream enablers to producing manufactured goods is particularly noteworthy; about one-third of the value of gross manufactures’ exports from developing economies is attributable to the value-added of “embodied” services inputs—with distribution (wholesale and retail) and business services making the largest contributions. These spillovers from services to manufacturing will only get stronger with the advent of “smart” production processes. For example, big data analytics that track shipments in real time and improved navigation systems that help route trucks based on current road conditions can make the transportation of goods more efficient.

Figure 2: Domestic value added embodied as inputs in economywide production, by industry, average across 118 countries, 2015

All in all, the changing nature of services deserves greater attention from policymakers. Modern ICT and professional services already resemble the manufacturing sector in terms of offering opportunities for scale, innovation, and spillovers. And while there is considerable room for catch-up among traditional services, the advent of digitization promises new growth opportunities. Treated as a residual economy for decades, the services sector stands poised to deliver the benefits associated with industrialization in the past.

Join the Conversation