An initial boom for Kenya – which experienced 44% growth per year up to 2005 – was followed by stagnation, exposing dangerous weaknesses in the sector’s pattern of growth. Too much of it was based on the largesse of U.S. policymakers, as opposed to the competitiveness of Kenya’s economy and the firms within it.

Competitiveness challenges

Where do some of the ruptures in Kenya’s textile and apparel competitive framework occur? Our survey of the sector revealed some interesting data on the challenges faced in both the investment climate and at the firm level: the two dimensions – the public/macro and private/micro – that together form the building blocks of sector competitiveness.

Power is clearly an issue across Sub-Saharan Africa – where investors quip that investing in Africa is a “ bring your own infrastructure” invitation. Kenya is no exception to that pattern. The government is actively addressing this issue, and the cost of power is coming down from levels of about 22 cents per kilowatt hour. However, it will take a while to come down to the level that China new enjoys, of between 5 and 7 cents per kwh. This is a problem for both textile and apparel firms, but textile firms feel the impact most acutely: Power accounts for about 25 percent of their operating costs. Part of the issue is that some firms in the sector are running on machines that are as much as 38 years old, so they consume a great deal of electricity by comparison to more up-to-date equipment.

Wages are higher in Kenya than in many competing countries. The ratio of the minimum wage to value added per worker is .92 in Kenya, compared to .53 in Lesotho and .36 in Bangladesh. “A race to the bottom” on wages is not a competition that Kenya wants to enter, yet the issue of productivity remains a major issue In a world where “fast fashion” buyers like Inditex of Spain, which has an army of more than 300 designers in its headquarters, are capable of delivering a new design to its thousands of stores in under two weeks, supplier productivity is all-important. Kenyan firms sometimes grapple with changeover times of just two weeks.

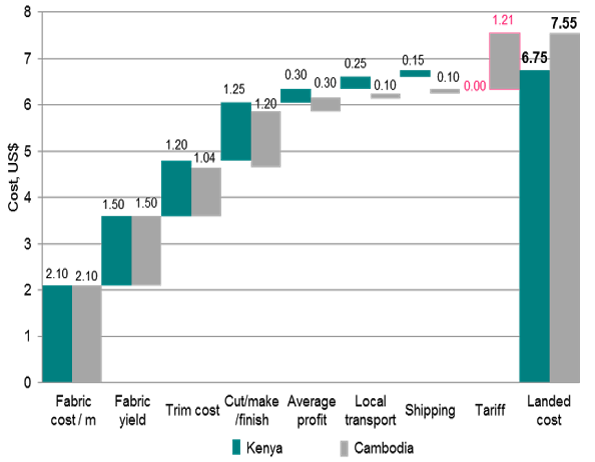

This all boils down to product-level cost competitiveness issues. Consider a pair of women’s jeans, comparing Kenya to Cambodia. The two countries have about the same cost for fabric – but, beyond that factor, Cambodia begins notching up cost advantages along each step of the production process: Its costs are 16 cents less on trim, 5 cents on cut and make, 15 cents on local transport, and so on. So by the time the two countries’ products arrive in the United States, the Kenyan pair of jeans is almost 50 cents more expensive than the Cambodian pair. It is only able to compete in the marketplace because of the $1.21 tariff on the Cambodian good.

Source: Kenya's National AGOA Strategy blog: http://agoastrategy.blogspot.com/

Seeking a competitive edge simply based on tariff advantages is a risky business model. So together with the government of Kenya and the private sector, our World Bank Group team is analyzing what must be done to help the textile and apparel sector shift its competitive profile.

If done right, a set of key initiatives will come together to create an ecosystem that forms the foundation of a dynamic, competitive industrial cluster that helps increase “stickiness,” giving firms reason to stay in the country. The factors that must come together transcend things like the cost of labour, which I personally hope will rise over time – and I say this as an ex-manufacturer who had a payroll to meet every month.

Building a pro-investment ecosystem

The electricity challenge faced by Kenyan firms is an issue – and it’s compounded by the outdated machinery that the sector often uses. So our team, together with other development partners and business associations, will be working with the sector to undertake energy audits, to see where they can make investments that will yield substantial cost-savings. An initial, high-level analysis points to potential energy savings between 4 percent to 25 percent, with cost savings from 10 percent to 50 percent per year.

With these investments and related cost-savings in mind, we’re working to link the sector to concessional financing that is tagged specifically to green investments. This will help address access to finance issues, which almost 70 percent of the sector say is a major bottleneck. (But, then again, who in the private sector would not say that is an issue?)

This type of investment makes sense in and off itself for the efficiencies and cost-savings that firms will generate. But it also opens up new market opportunities – something that almost 45 percent of the firms we surveyed said they needed. The global green market segment is expected to reach $3.5 trillion by 2017, and the Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability market in the United States alone is estimated to be about $290 billion annually, of which the Natural Lifestyle segment – including apparel – is $10.6 billion per year.

So while Kenyan firms will become more efficient producers for traditional niches – with the products that they are already exporting to the United States under AGOA, for example – they will also be able to explore new market opportunities. This will require specific market intelligence, so that producers will build the necessary confidence to take the plunge (or not, as some of them are likely to decide).

Taking on these new market opportunities will require rejiggering production bottlenecks – including tackling issues like the industry’s two-week changeover times. Moreover, there is also the issue of skills, at both the factory-floor level and the management level. Addressing this problem will require both government and private-sector effort, looking at where fundamental gaps are occurring. The solutions must focus on ensuring that the skills supply is more closely linked to demand by business – so that when a firm pays a training levy, they feel that it is going toward something from which they derive direct benefit.

In addition, building a complete pro-investment ecosystem requires looking at market channels and supporting access to buyers, particularly for new market segments. But Kenya also has local opportunities to build on. First, there is an obvious and, oddly, unfulfilled opportunity to build linkages between exporters in the export processing zone (EPZ) and the local textile industry. Back–of-the-envelope estimates by some EPZ apparel firms indicate that they would be willing to pay up to a 20-percent premium for locally sourced material, so long as they are ensured reliability of supply and compressed timeframes. So this gives Kenya’s textile manufacturers room in which to play.

Then there are opportunities in the public-procurement space, leveraging the country’s largest buyer to support local industry. Yet that should not occur unconditionally, because we are all aware that such support ultimately translates into a bill that must be picked up by the taxpayer. So price and quality criteria and sunset clauses will all be required.

Getting ready

At last year’s Origin Africa conference – the region’s main textile-and-apparel annual get-together – buyers and suppliers returned to a recurring message: that 2001 and the passage of AGOA brought short-term policy advantages that were not then converted to long-term, market-based competitive advantages. Now we have a second opportunity. The likelihood that AGOA will be renewed by the United States is looking increasingly positive, while buyers are more seriously looking at African countries as sourcing destinations.

Piecing together all of these interventions to develop a textile-and-apparel ecosystem that shifts Kenya’s competitive position will not be easy. But work on many of the critical areas has started. Kenya is positioning itself to play a bigger role in the global textile and apparel sector.

(Much of the Kenya textile-and-apparel sector data within this post comes from an upcoming Kenya sector analysis supported by the World Bank Group’s Trade and Competitiveness Global Practice.)

Join the Conversation