In addition to its human toll, the COVID-19 outbreak is expected to result in an economic recession at least as pronounced as the 2009 Global Financial Crisis. Mitigating the health implications of the pandemic is the foremost priority, but ensuring that firms weather the crisis and regain their vitality will be key to maintaining families’ livelihoods today and resuming economic growth afterward.

The impact of COVID-19 on businesses is occurring through four distinct channels: (1) a decline in demand for goods and services due to travel restrictions and shutdown measures; (2) reduced supply as firms are hampered by worker absences, productivity declines, and the disruption of global supply chains; (3) tightening of credit conditions and a liquidity crunch, as a result of the increase in uncertainty and risk aversion; (4) and a fall in investment as uncertainty about the length of the outbreak and the depth of its impact affects firms’ plans. In response, governments around the world have launched an extensive array of measures to support firms and jobs, many of them targeted specifically to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Since the onset of the outbreak, the World Bank has been cataloguing policy actions that have been announced in support of SMEs. The list of actions is not exhaustive and continues to be updated as further responses are announced. It also does not contain systematic information on their monetary value or other metrics that would allow an assessment of their magnitude. Still, with some 895 actions taken in 120 countries around the world (Map 1), we can already identify important differences in how countries are reacting to the crisis—and make some suggestions for countries that are still crafting their policy response package.

Map 1: Firm-support measures adopted in recent weeks in response to COVID-19

- High-income countries have been quicker to announce actions. About 80% of high-income countries have announced responses to the crisis, whereas only 32% among the lowest-income countries have taken actions.

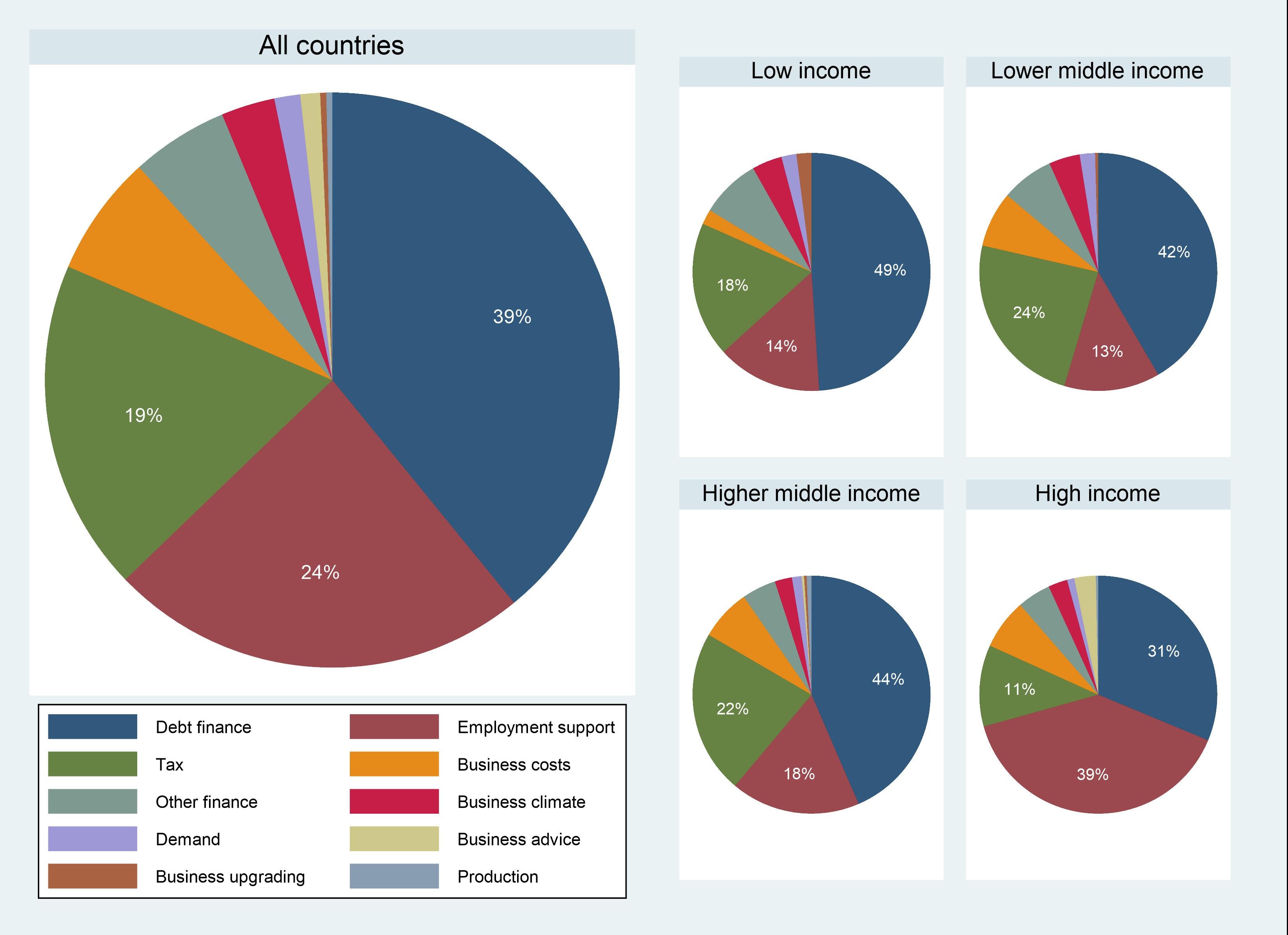

- Debt finance has been the most common instrument of choice. Across all countries (Figure 2a), debt finance support—new lending at concessional terms, payment deferrals, credit guarantees provided by governments, and central banks’ actions to induce commercial banks to increase lending to SMEs, such as lowering capital requirements—is the most common (39% of all support actions). Employment support (24%) is also prevalent—through wage subsidies and transfers to the self-employed—and tax support (19%).

- High-income countries have relied mostly on employment support measures, while lower-income economies have primarily utilized debt finance and tax support (figure 2b). The importance of employment support declines in line with a country’s per capita income: while these measures account for nearly 40% of the overall support in high-income economies, their importance declines to less than 15% in low and lower middle-income countries. Conversely, poorer economies rely much more on debt and tax instruments—as much as 49% and 18%, respectively—among low-income countries.

Figure 2: Type of SME Support

(All countries and by country income level)

Just what is the ideal policy response package for lower-income economies? It will depend on the landscape of firms and the country’s administrative capabilities, as well as the financial sector soundness and fiscal capacity. While it is difficult to generalize, it is probably safe to say that many of the responses adopted in high-income countries may not be well suited for developing economies. In countries with large informal sectors, social protection and cash transfer programs provide the most direct way to reach working families, but they could also be complemented by specific support to firms. Tax relief and support through the formal banking channel may not reach most firms in such countries, but it can keep otherwise viable firms from slipping into informality or bankruptcy, improving the prospects of a speedy recovery. This is particularly relevant if we consider that it is the middle segment where there is the greatest potential loss of human and organizational capital.

Where social protection systems are less developed, support to informal firms may be an alternative way to reach workers. This could include facilitating access to working capital through remittances and community-based financial institutions, providing rent and utility subsidies, and leveraging mobile and digital payments technology.

In designing and implementing effective and timely responses, the following are important:

- Focus on supporting firms and jobs. Adverse shocks usually affect specific firms, sectors or locations. In normal times, a simple reallocation of resources helps an economy absorb those shocks and diffuse the impact on productivity. In situations like those, policies should focus on protecting workers, not jobs. In the current crisis, however, the lockdown is affecting all businesses and threatening to break links between firms and workers. Policies should now aim to reduce the rupture of such links, both to help workers and to expedite the economic recovery.

- Critical value chains must function throughout lockdowns, including transport and logistics, food markets, pharmacies and other health-care services. Yet food value chains are being disrupted because workers cannot harvest crops, farmers cannot transport goods to market, or traditional markets are closed. To maintain these and other essential services, business models can be adapted to operate with social distancing and good health practices, and use technology (fintech, e-commerce) to limit face-to-face contact. Support to large private firms and state-owned enterprises may be necessary to maintain these value chains.

- In countries with limited fiscal capacity and significant financial sector vulnerabilities, the design and implementation of these programs need to consider these restrictions. With corporate and government debt at record levels, the tight interlinkages between sovereigns, banks, and the corporate sector in some countries may give rise to adverse feedback loops which could be exacerbated by the consequences of the pandemic.

- Follow a phased approach. At present there is an urgent need to adopt emergency measures that provide firms with much needed liquidity, reduce worker layoffs, and avoid permanent closures and bankruptcies. After helping viable businesses “keep the lights on” through the crisis, in the recovery phase, government policy should focus on boosting firm productivity and putting economies back on a growth path: promoting investment, reactivating supply chains, and even establishing temporary job creation programs.

- Ensure that emergency measures are transparent and time bound. Most interventions—especially those during the emergency response phase—should have simple rules and be phased out as the pandemic subsides. It is critical to avoid time-consistency problems and capture by specific interests by communicating in a cogent and transparent manner the rationale for supporting firms and the duration of policy interventions, with clear and credible sunsets.

- Increase targeting over time. To act quickly, initial responses should be broad-based and targeting should be kept as simple as possible, limited to the locations and sectors that are initially hit the hardest, and expand as the effect of the shock propagates. During the recovery phase, support policies could be targeted to more specific groups of beneficiaries, with the objective of steering resources toward more productive firms.

Editor’s note: In this blog, country income levels are defined by quartiles of the distribution of 2018 gross national income per capita. Data come from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.

Join the Conversation