The World Economic Forum describes this transformation as the “Fourth Industrial Revolution,” because the speed and extent of disruption is unprecedented.

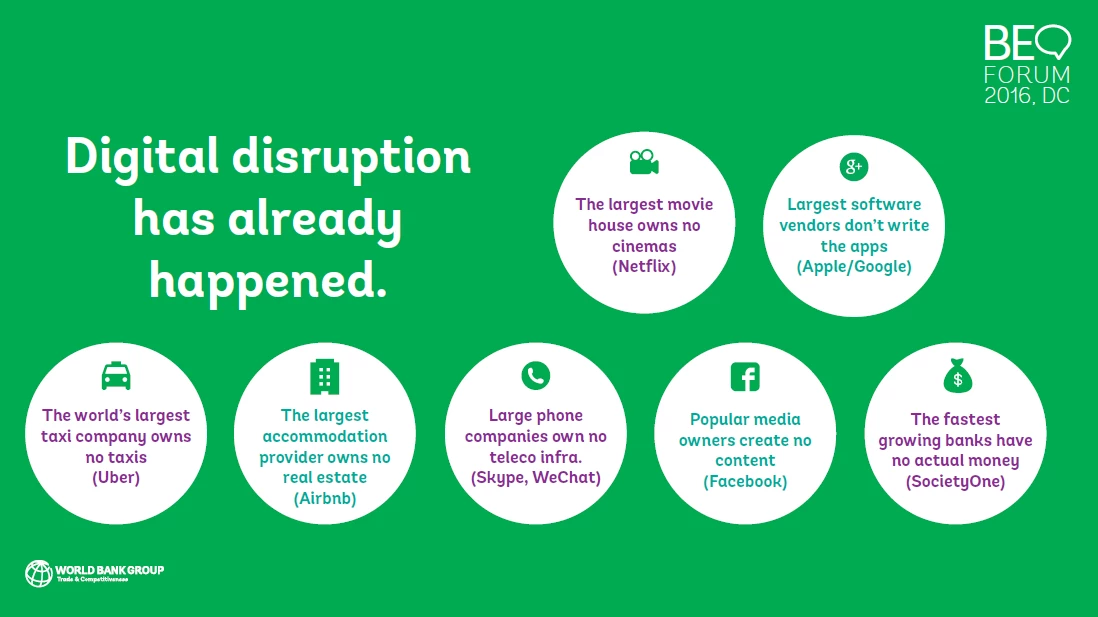

A key trend of this revolution is the emergence of technology-enabled, peer-to-peer and business-to-peer platforms that facilitate commerce. These platforms – most commonly referred to as the “sharing economy” or the “collaborative consumption economy” – have grown exponentially in recent years, disrupting existing industry structures and value chains in developed and emerging markets.

Notably, growing internet and mobile penetration catalyzed the growth of disruptive firms and innovations, such as Uber and Airbnb, in a number of middle- and low-income countries. However, as highlighted by the 2016 World Development Report, for this digital revolution to be inclusive, and for it produce dividends for the poor, its “analog complements” – such as the institutions that are accountable to citizens and the regulations that enable workers to access and leverage this new economy – should also be in place.

The global proliferation of these collaborative platforms poses new challenges for regulators trying to keep pace with rapidly evolving business models. This issue was at the heart of discussions between former Head of Public Policy at Facebook, Uber and DJI, Corey Owens, and Professor of Law at Howard University and former regulator at the Federal Trade Commission, Andy Gavil, at the 2016 Business Environment Forum that took place in Washington from May 17 to 19.

The sharing economy presents opportunities for regulators.

New collaborative platforms can perform some of the functions carried out by traditional regulatory frameworks. This can occur in several ways.

First, many technologies embed effective feedback mechanisms through producer and consumer ratings. These feedback mechanisms generate trust amongusers and reduce information asymmetries in a more transparent, reliable and efficient manner than traditional regulation. That contributes to consumer protection and safety.

Second, the private owners of these platforms now collect an unprecedented amount of data in the markets in which they operate. Collected information includes data on tax receipts, consumer habits, traffic patterns and driver safety, to name a few. These newly available insights are particularly important because they are surfacing in markets where data was traditionally scarce and may even have been nonexistent. Regulators and tax authorities can leverage the data to design policies, improve implementation, boost tax collection and achieve better regulatory outcomes.

Third, collaborative platforms may also present an opportunity to improve formality in activities that are traditionally difficult to monitor, since all transactions facilitated by the platforms are recorded online and through bank accounts.

Despite their benefits, new "sharing economy" technologies pose challenges for regulators.

What commentators lump under the term “sharing economy” are at least four different for-profit and nonprofit activities that have radically different implications for competition and the business environment. For-profit activities span a variety of sectors and encompass a range of economic activities, from renting assets (Airbnb, Bikeshare) to providing a combination of asset rental with service provision (ridesharing applications such as Uber), or purely selling services (TaskRabbit). As a result, developing a uniform regulatory response is highly challenging.

Common denominators for technology-based platforms include lower barriers to entry for platform creators and service providers, as well as lower transaction costs and fewer information asymmetries for consumers. These qualities buttress the platforms’ success and often make traditional operators (e.g., hotels or taxis) hostile to sharing-economy actors. Incumbent firms find refuge behind prescriptive legacy regulations that reflect their industry standards in order to exclude new business models. A recent example of this is the ban imposed on Uber’s discount services, offered by non-professional drivers in France, Germany, Spain and Italy where local taxi drivers successfully argued that certain ridesharing offerings represented unfair competition for standard taxi services and did not comply with strict transportation regulations. Receptive jurisdictions have responded by moving away from prescriptive standards toward standards based on performance, which are more malleable. For example, under performance standards, a taxi is not strictly defined as a yellow car for hire with four passenger seats, a taxi meter and a sign on top, but rather any private car transporting passengers for hire. While more adaptable performance standards pose challenges for weak regulatory regimes, they also typically require more resources for auditing and leave more room for discretion in enforcement. As such, prescriptive, black-and-white regulations may be easier to implement and may be less prone to corruption, but may also act as barriers to entry and innovation.

Striking a balance between flexible regulation to accommodate new platforms in a level playing field and the regulation of legitimate public-interest issues puts pressure on local institutions. For example, occupational safety and consumer protection cannot be fully delegated to private companies. Even if private actors are better positioned to protect the public interest, their economic interests may disincentivize private efforts to protect the public good. Moreover, regulators should be mindful that disruptive firms may eventually gain disproportionate market share due to network effects, a situation in which the concentration of market power may pose significant pressures to local institutions. Developing countries may be more prone to such pressures as the number of platforms operating locally may be limited when compared to more developed markets. Moreover, personal data accumulation poses a host of privacy challenges. Regulators should develop robust frameworks to account for privacy and consumer-protection concerns and should oversee the ways through which private entities monetize the use of user information.

The ease with which individuals can now connect, cooperate, share information, share assets and obtain services is truly transformative. At the same time, since we are at the infancy of this new era, the extent of transformation in the way we do business is difficult to grasp. Although collaborative platforms disrupt local industries, companies and communities – and can even eliminate traditional jobs – their benefits may outweigh their costs. By empowering citizens, increasing productivity and efficiency, boosting overall employment, improving market access, reducing transaction costs or even diminishing carbon footprint, shared-economy facilitators – if properly regulated – can improve outcomes for the bottom quintile of the population by opening markets and unlocking opportunities for the poor, both as producers and consumers.

Footnote 1: In 2012, the combined value of trade in goods and services plus financial flows reached a nominal value of US $26 trillion, or 36 percent of global GDP – lower than the US $29.3 trillion or 52.4 percent of global GDP in 2007. At the same time, global online traffic has grown from 84 petabytes per month in 2000 to more than 40,000 petabytes per month in 2012 — a 500-fold increase. (Source: "Global flows in a digital age: How trade, finance, people and data connect the world economy," McKinsey Global Institute.)

Join the Conversation