wind turbines in Bulgaria

wind turbines in Bulgaria

With more than $40 trillion of funds under sustainable management, Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investing is no longer niche investing, having finally struck a chord with mainstream finance. Without doubt, most investors in this realm have an authentic interest in promoting a more sustainable and equitable future. But getting sustainability right is a complicated business.

A thorough debate about sustainable growth can quickly lead into a discussion about development finance, long-term economic growth, natural resources, institutions, and politics among other issues. It is not too far-fetched to compare the multitude of factors and level of coordination that go into building a sustainable ESG investment framework to conducting an orchestra of classical musicians to perform a full symphony.

Financial markets embracing a more sustainable future is music to the ears of those working in international development. With a history in the sustainable finance sphere spanning some 70 years, the World Bank Group has been a key protagonist in helping the financial sector embrace a more sustainable future. The current pandemic is seeing a renewed global push to build back better, more equitable and sustainable economies. At the dawn of this hopeful recovery, it also makes sense to assess how ESG investing can further this trend. Reading a printed music score enables a better understanding of a musical performance. In that spirit, we asked seven leading sovereign ESG data and score providers—FTSE Russell/Beyond Ratings, IIS, MSCI, RepRisk, Robeco, Sustainalytics, and V.E—for methodology and background documents to better understand their sovereign ESG scoring systems.

Two recent papers, Demystifying Sovereign ESG and A New Dawn—Rethinking Sovereign ESG, are the results of this effort. They describe the current state of sovereign ESG investing and provide clarity on what “ESG as input” means versus “ESG as output”, and how it relates to “values” versus “value” investing or purpose versus purpose-neutral investing. Most importantly, they reveal that the current sovereign ESG framework faces structural challenges that must be addressed.

Sovereign ESG providers, who have laid the foundation for the operationalization of ESG investing in sovereign fixed income markets, generally agree on what constitutes a good sovereign performance for Governance and Social issues. But there is considerably less agreement on what constitutes a good score on the Environment pillar. This is due to disagreements on what “good” performance is on a conceptual level, but also due to data gaps, out-of-date statistics, and heterogeneous reporting standards, which often force providers to fill in and estimate missing values. Fortunately, recent advances in geospatial technologies, as well as pressure for more standardized national reporting and the newest version of the Changing Wealth of Nations data show promise for mending these gaps.

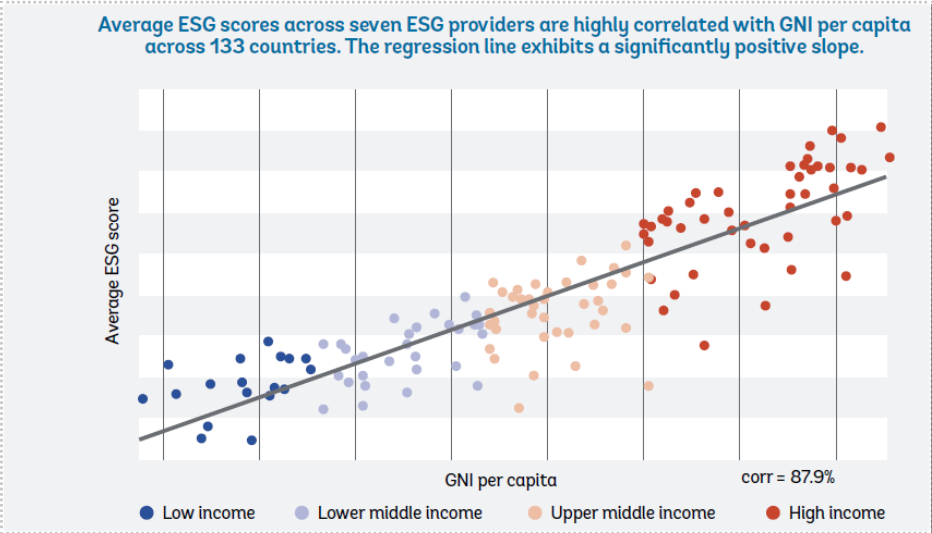

While agreement among ESG providers on Governance and Social scores may appear desirable at first glance, further investigation reveals that this may not be desirable after all. This is because of an ingrained income bias (IIB). About 90 percent of sovereign ESG scores can be explained by a country’s national income.

Sovereign ESG scores have a strong income bias

Higher income countries tend to have stronger institutions and less inequality. This drives ESG scores higher. The first-order effect of the income bias is that an ESG-tilted portfolio—which assigns higher weights to countries with higher ESG scores—will inevitably allocate funds toward richer countries. This means that ESG investing would drive capital away from low-income countries and thereby widen funding gaps to reach Sustainable Development Goals. The second-order effect is about the signal that these scores send to middle- and lower-income countries. If ESG scores are so closely linked to income, how can developing economies compete with industrialized nations in the ESG arena? In fact, what short-term policy efforts would affect a nation’s income enough to obtain better ESG scores?

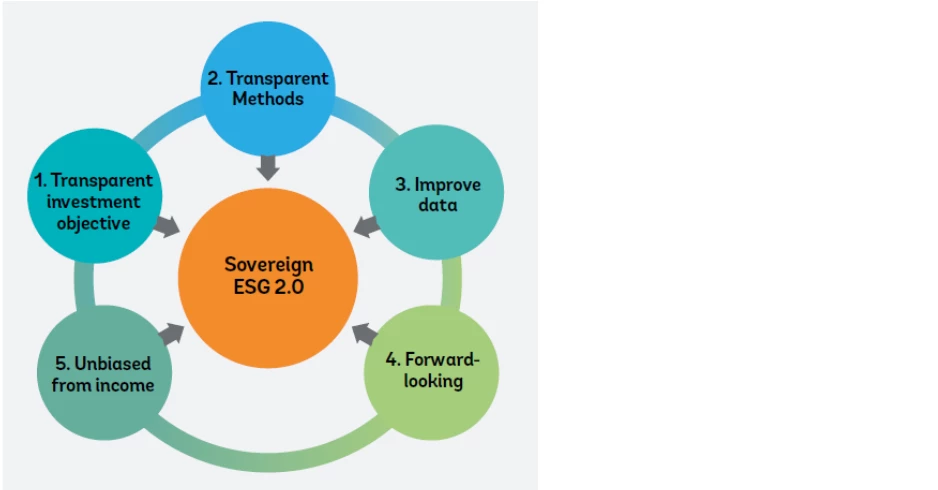

Sovereign ESG needs to correct course toward a more transparent “Sovereign ESG 2.0”. This framework builds upon existing sovereign ESG systems but differentiates itself through five guiding principles: clarity on investment objectives, transparency of scoring methodology, improved data, incorporation of forward-looking scenarios, and accounting for the ingrained income bias. The papers discuss why this framework supplies investors with additional, meaningful information about a country’s ESG performance.

Key requirement of Sovereign ESG 2.0

Sustainability is a complex topic and it is important that market practices embedded in the financial system are equitable and transparent for all. It’s important that policy makers are cognizant of the current shortcomings and that multilateral development banks and governments of advanced economies support middle- and low-income countries in their efforts to make their economies more sustainable. Depending on conditions in the country, this work may or may not be through the sovereign debt market. Although sovereign ESG investing is certainly one lever to attract ESG-orientated capital, other methods such as taxation and regulatory changes should not be disregarded.

The World Bank is a primary provider of input data used by sovereign ESG providers and is actively working to make this transition a reality. Our goal is not to stop the music, but to examine the popularity of sovereign ESG scores with a healthy amount of skepticism. By bringing in our expertise into the discussion, we want to help sovereign ESG scores strike the right chords and sing meaningful lyrics.

Join the Conversation