Chile and Uruguay broke new ground this year by selling bonds whose costs will be linked to meeting climate sustainability goals. On its $2 billion borrowing in March, Chile will have to pay more interest if it misses targets for cutting carbon dioxide emissions and expanding renewable energy. In the case of Uruguay’s $1.5 billion October issue, the rates will rise or fall depending on whether the country meets emissions and forest targets.

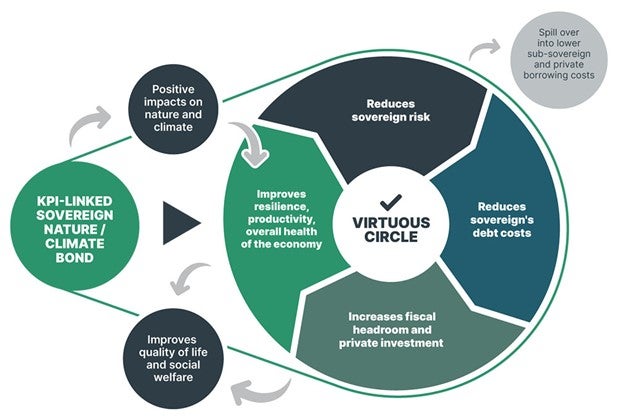

The two borrowings show how the normally staid sovereign debt world has begun rapidly evolving. The bonds are examples of sustainability-linked financing,. which we discussed in our previous posting. As our partners at the Sustainability-linked Sovereign Debt Hub point out, today’s sovereign debt markets are not fit for purpose, as they fail to take adequate account of the sustainability risks which increasingly are having a material impact on countries’ economic growth and resilience. Vulnerable nations are excluded from accessing the affordable capital and investment that is urgently needed to create a sustainable economy.

The two sovereign SLBs aim to break this cycle – setting the stage for further growth of an asset class which is rapidly taking off in the corporate sector. Chile’s $2 billion 20 year issuance in March comes with a 12.5 basis point a year ‘step up’ in interest if one of two what are known as key performance indicator (KPI) targets – environmental targets that the government commits to meet - are missed. In the case of Chile, the country has committed to emit no more than 95 million metric tons of carbon dioxide by 2030; and that 60% of its electricity production will be generated from renewable energy by 2032. Uruguay’s $1.5 billion issuance goes – literally- a step further with a two-way pricing structure: 30 basis point step up or down based on performance against two NDC targets related to the GHG intensity of the economy and native forest cover. Both bonds were reportedly more than double over-subscribed, and, importantly, attracted new investors to the countries’ sovereign debt markets.

So far sovereign SLB issuance has been carried by two countries with investment grade status. The question is how to build on this momentum and start to mobilize capital at a scale for the large set of countries struggling with the debt-nature-climate challenge? Lower-rated sovereigns would benefit from improved market access with the use of credit enhancements. The IMF’s recent Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR) includes the strong message that “scaling up private climate finance will require new finance instruments and the involvement of MDBs to attract private financing.”

One of the main challenges for the scalability of Sustainability-linked financing is market access as there is a mismatch in the risk-return appetite of borrowers and investors. Another is how to wisely use scarce ‘concessional’ capital of DFIs and MDBs. A third is to how design structures that would be as simple and standardized as possible. Ideally these would be close to or the same as plain vanilla investments - avoiding the creation of niche debt instruments that could reduce liquidity of sovereign debt markets.

One innovation that could help boost sustainability-linked finance would be to make the level of reward to governments dependent on hitting truly ambitious targets. Setting the bar too low has been a major criticisms of the issuance of SBLs by corporates to date – not least through excellent analysis from our IFC colleagues. We continue to work on the concept of model-based goals as a way to tackle this challenge by recognizing and rewarding the real achievements of sustainability policies. We also look forward to working with the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) on standard setting work for sovereign SLBs building on the framework for indicators we previously proposed. In addition, our IMF colleagues recently pointed out that KPI measuring climate outcomes could also have its place in improving design of debt for climate swaps.

On the financial structure side, credit enhancements could be used in different ways. One option would be a fund that would invest in conventional debt of countries following pre-agreed sustainability commitments. DFIs and donors could provide capital that would be most subject to ‘first-loss’ style risk as a way of mobilizing other investors to take credit enhanced, senior debt tranches. This would also help to scale up the market.

Similar types of funds and structures have already been successfully implemented, such as the $1.42 billion IFC-Amundi EGO fund set up in 2018. An innovative twist could be that, as a further incentive, DFIs would funnel some of their returns earned from investing in the fund back to countries that meet their goals This could improve market access for governments , use of below-market, concessional finance from DFIs to leverage private capital, and avoid the fragmentation of sovereign debt markets.

At the level of individual bonds, there could be similar incentive structures - linking the improved financing conditions brought by credit enhancements to the achievement of the commitment targets. Low-cost capital provided by DFIs could be used to credit enhance debt via first-loss, subordinated structures, or by financing collateral such as (highly-rated) zero coupon bonds.

Stepping up to the challenge and creating a virtuous circle of rewards will require us all – issuers, investors and the concessional finance community alike- to step out of our comfort zone.

Join the Conversation