Man sorting recyclables into different baskets.

Man sorting recyclables into different baskets.

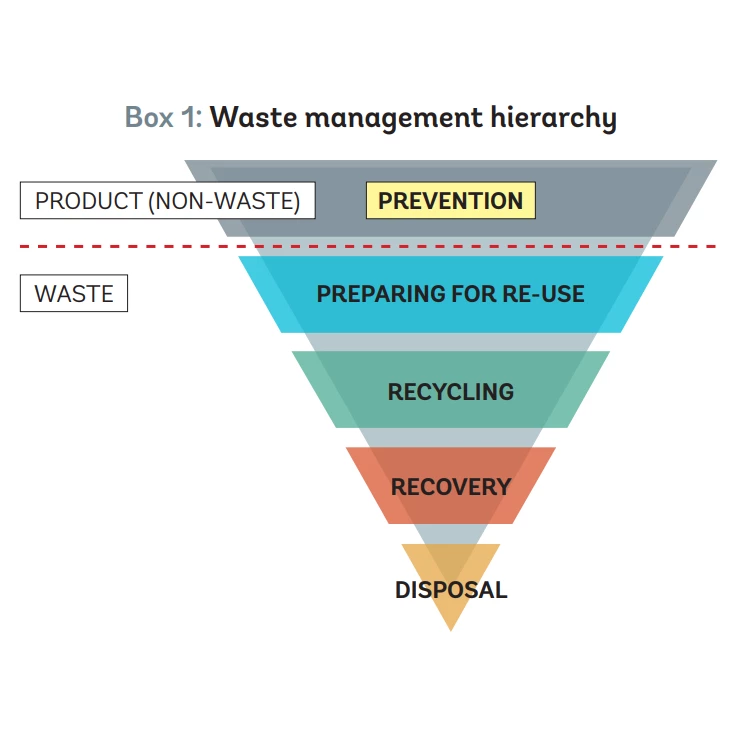

Solid waste management amounts to approximately 5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, with landfills being the primary source. As climate change continues to pose an ever-looming existential threat to the world and its inhabitants, managing waste more sustainably and efficiently is critical (See figure 1). The waste management process involves many stakeholders, including businesses, governments, households, community organizations, and waste pickers. These stakeholders influence where and how waste is generated, sorted, recycled, and disposed of, and how waste services are paid for. In a recently published report “Behavior change in solid waste management: A compendium of cases,” we assessed 30 case studies from different countries with a mix of income levels and geographies to explore how behavioral changes can vastly help improve waste management.

Figure 1. Waste Management Hierarchy

Source: TheGPSC.org

Successful waste management depends on stakeholder participation, social support, and a strong social contract with citizens. Many barriers hinder people from adopting sustainable waste-related practices, including ingrained habits, lack of knowledge, inconvenience, time burdens, and structural limitations such as inadequate infrastructure or prohibitive costs.

Behavioral scientists have investigated what influences people’s decision-making and the necessary tools to facilitate actionable change. These tools can complement traditional policies and make it easier for people to adopt sustainable waste management practices. For example, Korea introduced eco-labeling regimes to make it easier for consumers to purchase more recycled or refillable products. Tonga created a feedback mechanism to allow residents to comment on service delivery and offer suggestions for improvements.

Charging lower fees for households who participate in sorting their waste into different categories (e.g., recyclables) can improve participation rates and more sustainable outcomes. For instance, in Romania, the government decreased the size of residual waste containers to deter unnecessary binning and residents paid lower collection fees if they sorted their waste.

The case studies in our report tackle three distinct categories of behaviors, looking at how to get people to:

i) use waste services,

ii) be more sustainable with their waste disposal, and

iii) generate less waste.

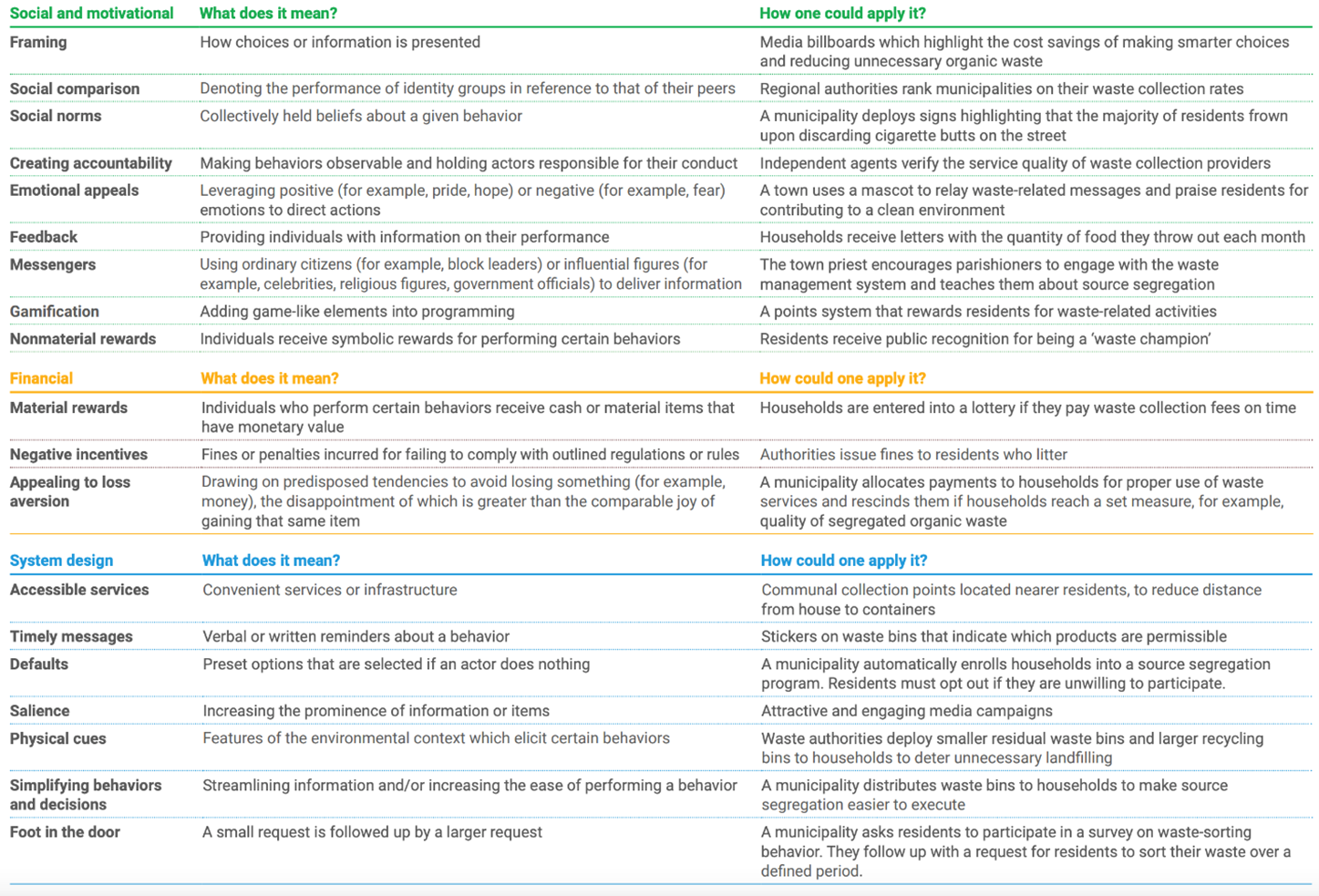

The case studies look at what motivates stakeholders and the mechanisms that can help change waste management behaviors:

- Financial mechanisms: Positive, negative, or randomly assigned incentives influence behaviors differently. We include both traditional tools and variations recommended by behavioral science, such as material rewards and negative incentives. For example, in Sălacea, Romania, the government used negative incentives to deter littering. Government officials mailed letters to the residents’ address, along with a fine (e.g., EUR 100) making a clear association between the undesired behavior and its consequences.

- Social and motivational mechanisms: Social networks, personal motivations, and peer expectations can encourage behavior change. For instance, highlighting that most people in a community recycle can motivate others to do the same. In Oldham, near Manchester in the United Kingdom, recognizing above and below average recycling performance with smiley and frown face emojis encouraged food waste recycling.

- System design mechanisms: Changing the physical environment can facilitate desired behaviors or discourage undesired behaviors. For example, placing recycling bins in convenient locations or making them more visually prominent can encourage people to recycle. In Colombia, the government introduced the Green Containers Program and distributed bins and Bokashi (a composting material made of rice or wheat bran) to households, making it easier for households to compost. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2. Green Containers Program in Colombia

Source: Empresa de Servicios Públicos de Cajicá

These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. The choice of mechanism is situationally dependent. Since there are often multiple barriers to making environmentally friendly decisions, these mechanisms can work together to guide behavioral change. See some of the tools in the figure below.

Figure 3. Mechanisms to promote behavior change

By understanding the factors that influence decision-making and incorporating behavioral tools, policymakers can promote sustainable waste management behaviors. To learn more, read our report, and visit our website. What tools would be the most helpful for your city or community?

Join the Conversation