The trade war between China and the United States is hurting consumers and producers in both countries. As two recent papers show, US consumers are facing significantly higher prices as a result of the tariffs. In addition, producers are losing foreign sales as demand for the targeted goods declines.

Their loss has turned out to be a boon – for now – for exporters of competing products from other nations. Exporters from Brazil, the European Union, Malaysia, Mexico, and India, have substituted lost sales from US and China in each other’s markets. A number of small exporters have also benefitted from large percentage increases in exports.

Among economists, the effects of new tariffs between the US and China were expected – it is basic supply and demand. The tariffs imposed on Chinese and American goods made them more expensive, increasing prices for consumers in both countries. Faced with higher prices, importers of goods look for substitutes, which benefits exporters from the rest of the world.

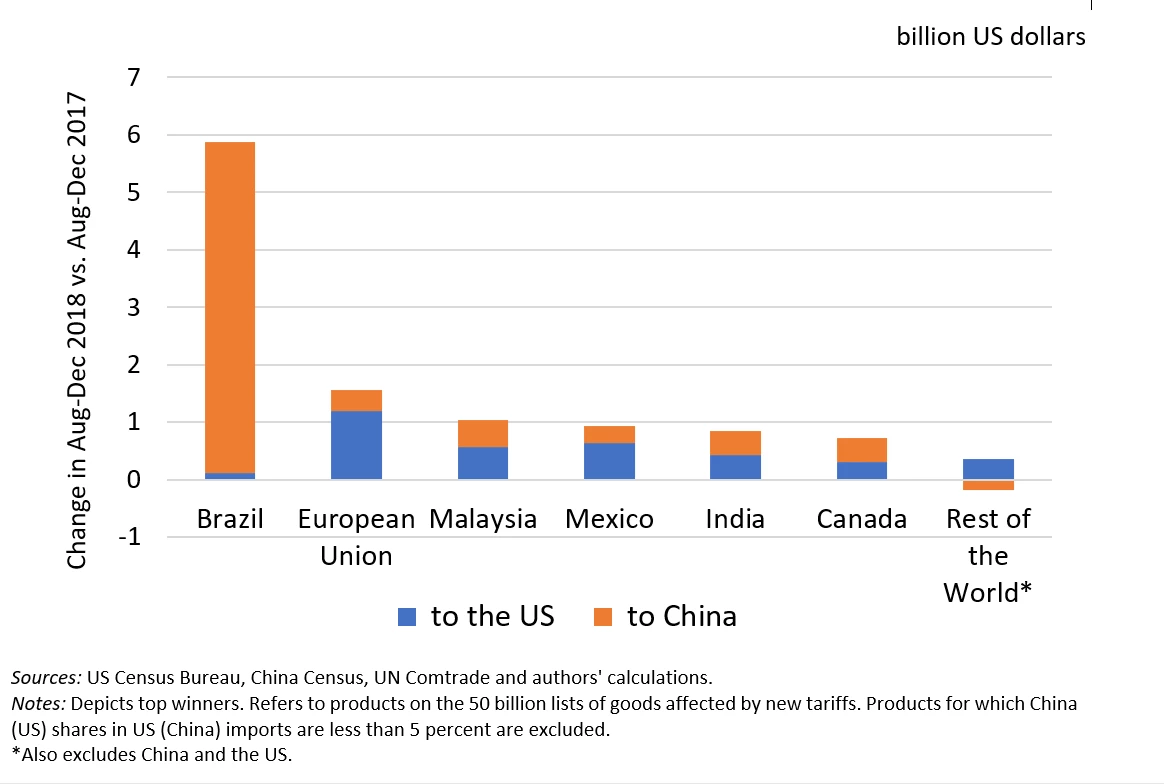

Large exporters, such as Brazil, the European Union, Malaysia, and Mexico have been the big aggregate beneficiaries, with Brazil exporting almost $6 billion in additional goods relative to the previous year in product categories where US goods face tariffs. The EU, with its large and diversified export basket, has benefited from both sides’ tariffs – increasing exports to the US and China as a result. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1. Changes in exports to the US and China of tariff-affected products on the $50 bn lists

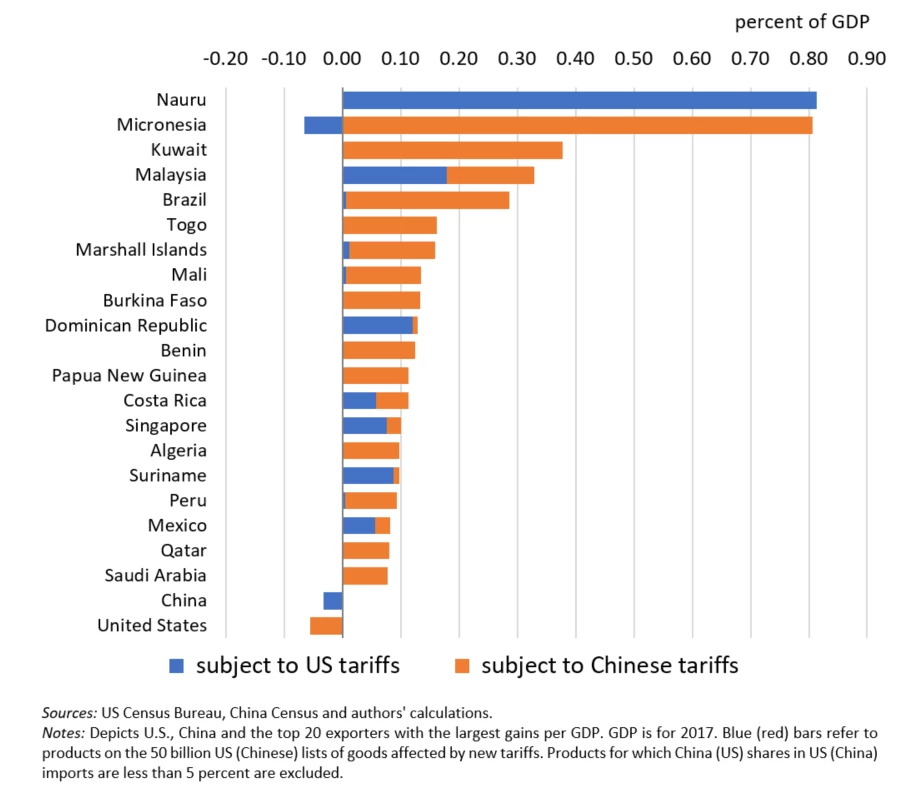

Relative to country size, many poorer countries have also benefitted. As a share of GDP, the tiny Pacific islands of Micronesia and Nauru have increased exports by 0.8 percentage points, due to a relative surge in exports of electrical switches from Nauru to the US, and of skipjack tuna from Micronesia to China. Kuwait (due to Chinese tariffs on American propane), Malaysia (due to exports of electronic integrated circuits to the US and copper waste and scrap to China), and Brazil (due to Chinese tariffs on US agriculture products) have also seen substantial increases in exports relative to GDP (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Changes in exports to the US and China, as a share of countries’ GDP, Aug-Dec 2018 vs. Aug-Dec. 2017

Substitutability matters

Data from the initial round of $50 billion in tariffs – which have been in place since the summer 2018 - show that for developing countries looking to take advantage of the current price difference created by the tariffs, substitutability matters. That is why Brazil has been able to increase its exports so drastically over the past few months. For Chinese importers, Brazilian soybeans are pretty similar to American soybeans. But flipped the other way, American importers have a harder time finding substitutes for products from China, which often include highly customized electronics that are less easily obtained from non-Chinese markets.

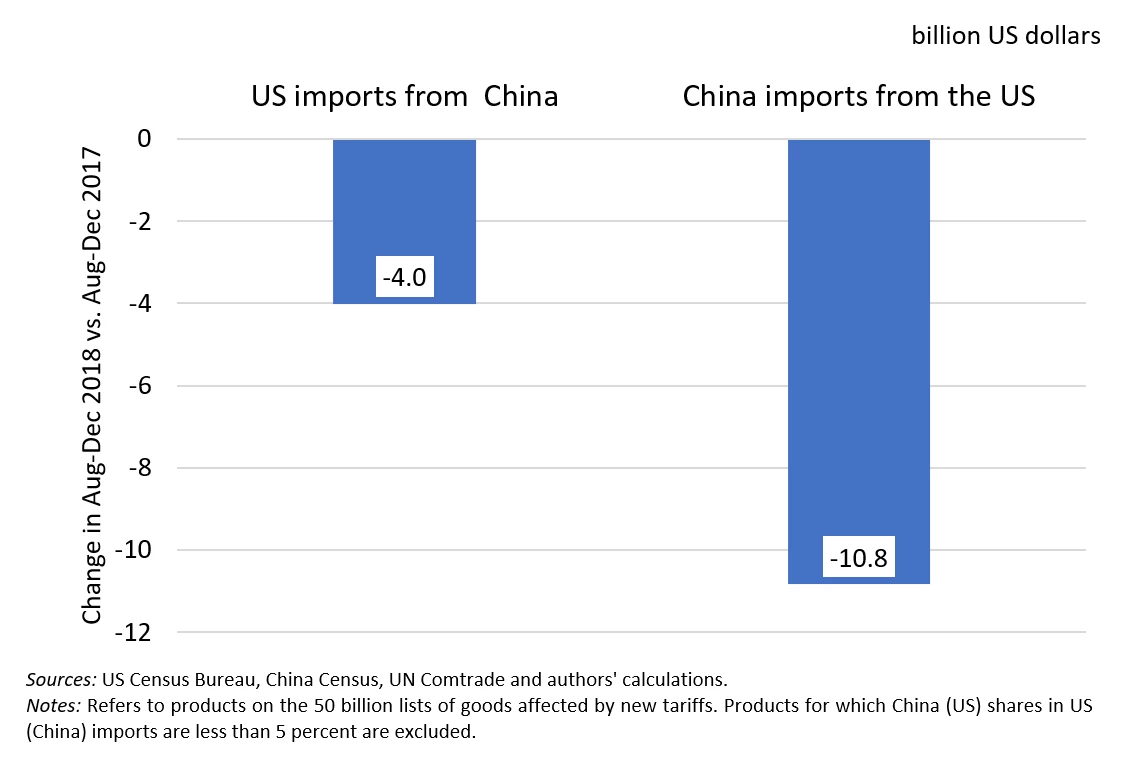

The diversion means that US exporters of the targeted goods have been hurt relatively more in the initial round of tariffs. Following the announcement of the tariffs, both China and American exports have declined. But US exports have declined by close to $11 billion compared to just $4 billion from China (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Changes in the US and China bilateral trade of tariff-affected products on the $50 bn lists

Short-run gains versus long-term risks

Does that mean the trade war can be beneficial for developing countries? In the short run, perhaps. But in the medium run, there are important risks. Just as trade models predicted that other countries will gain, as has occurred, trade models can predict what will happen if tensions escalate.

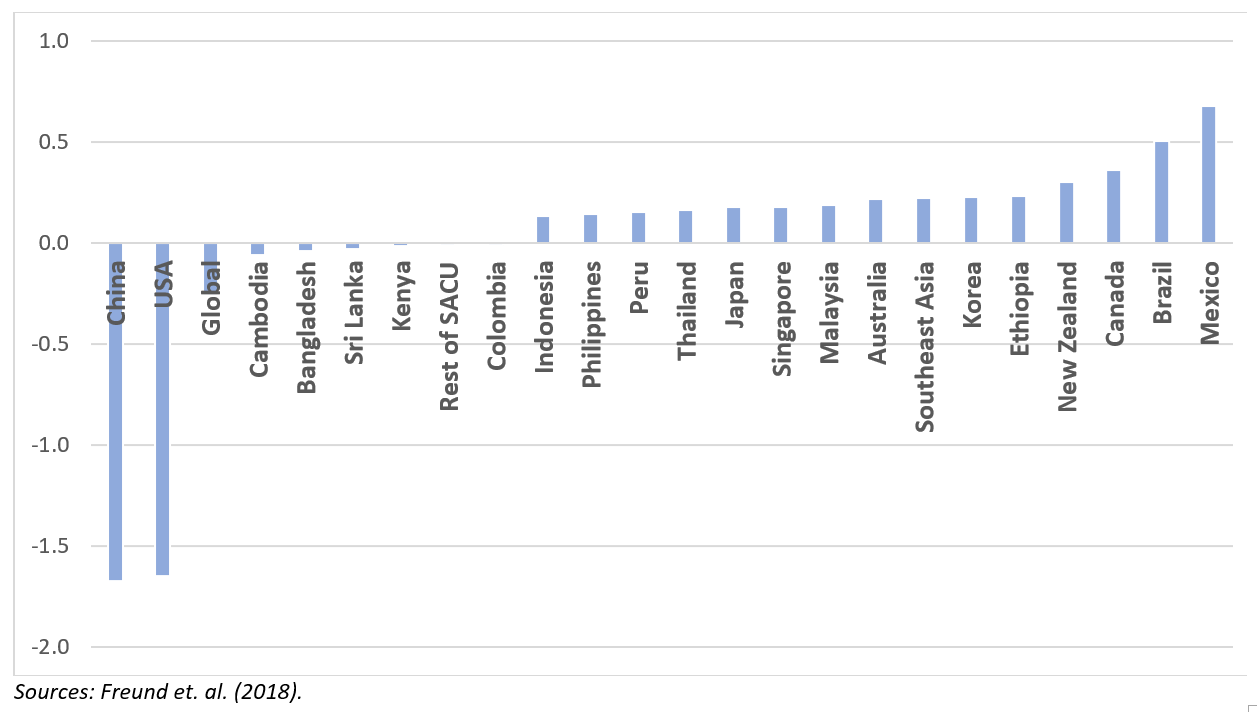

We estimate that several developing countries (Mexico, Malaysia, Vietnam) would be expected to achieve net gains in terms of total exports and income in line with the impacts observed to date (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Simulated impacts of trade tensions (Lists 1 and 2 implemented) on total exports in the medium run (% deviations from the baseline)

But, in a more severe trade war, our estimates suggest there are real costs, with losses occurring in all regions. By shaking investor confidence, the escalation to a full-blown trade war could:

- Reduce global exports by up to 3 percent (at a cost of US$674 billion);

- Reduce global income by up to 1.7 percent (or US$1.4 trillion);

Roughly half of the global income loss of 1.7 percent would be due to loss of income by developing countries (excluding China) and a third of the global exports decline of 2.7 percent would be due to the loss of exports of developing countries (excluding China). Trade tensions would depress trade, disrupt global supply chains, and divert trade away from developing countries.

The bottom line is that short-term benefits for developing countries notwithstanding, there are no real winners in a trade war. For the US, China, and developing countries alike, the news that negotiations between the two superpowers may be reaching a resolution soon is welcome. An open, rules-based trading system is the best way for all countries to use their comparative advantages to increase growth and reduce poverty.

Join the Conversation