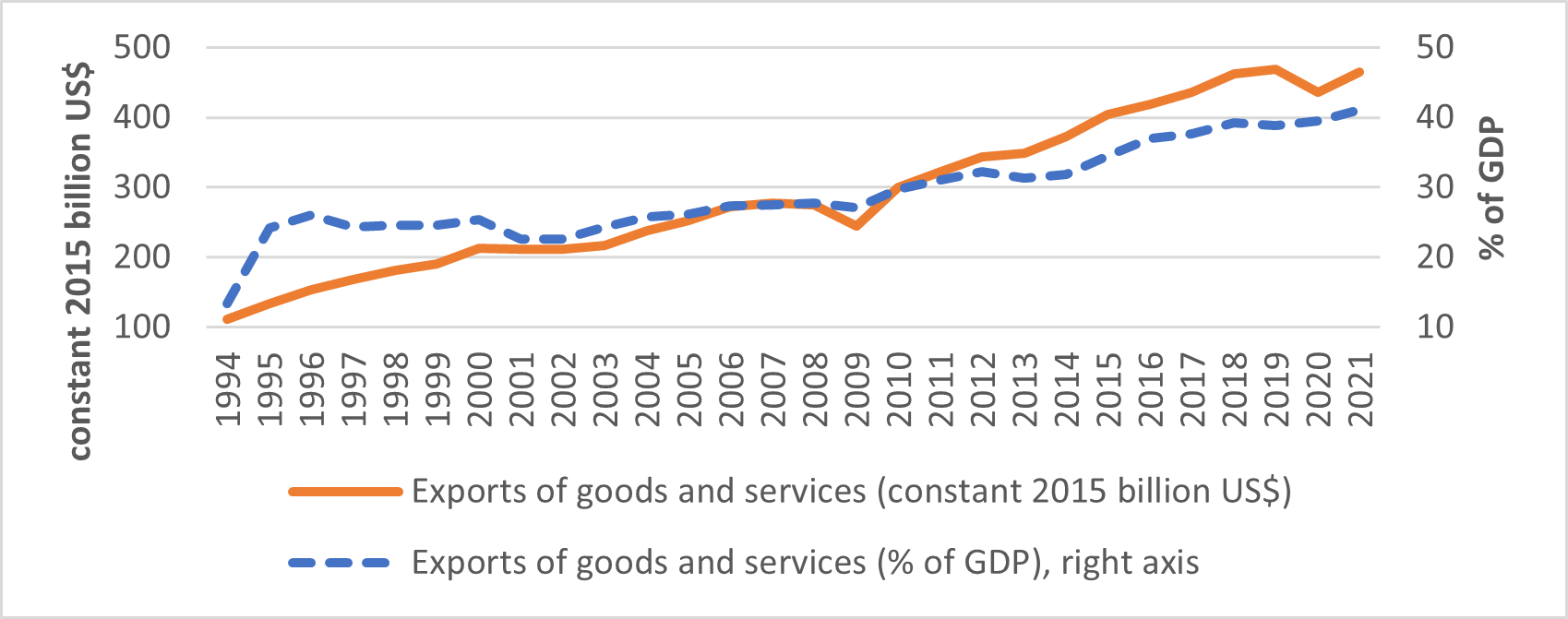

Trade liberalization has helped Mexico become an export superstar. Exports of goods and services as a share of GDP more than doubled to 41 percent from 1994 to 2021. In the same period, the value of Mexico’s exports in constant dollars rose more than fourfold to US$465 billion (Figure 1) – a pace that compares favorably with countries such as Thailand and Malaysia.

Figure 1: Mexico’s exports take off

Mexico’s exports took off after it joined the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, which resulted in significant trade liberalization and diversification away from oil. NAFTA removed most tariffs on goods traded between Canada, Mexico, and the United States and eliminated barriers to cross-border investment. The 2018 United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) is in large part similar to the NAFTA and is likely to preserve Mexico’s strong trade ties with its neighbors to the North.

A new World Bank study looks at how trade has affected local labor markets in the country of almost 130 million people. Among its findings: Booming exports of goods including transport equipment, machinery, and electrical equipment have helped draw more Mexican workers into formal employment, providing them with pensions and job security that they previously lacked. Accessing better jobs required workers to migrate to regions in Mexico’s North where export production is concentrated.

Exports help workers move out of informality

Our study uses a unique dataset matching information on trade with labor market indicators for around 2,000 Mexican municipalities over the period 2004-2014. Specifically, we tested whether trade expansion increased the share of employed, salaries and incomes of both formal and informal workers, immigration, and formality. One key takeaway is that labor market outcomes from trade are nuanced. Trade expansion in Mexico tends to affect local labor markets more strongly through reductions in informality and an influx of domestic migrants , rather than through increases in the share of employed workers or average salaries and incomes.

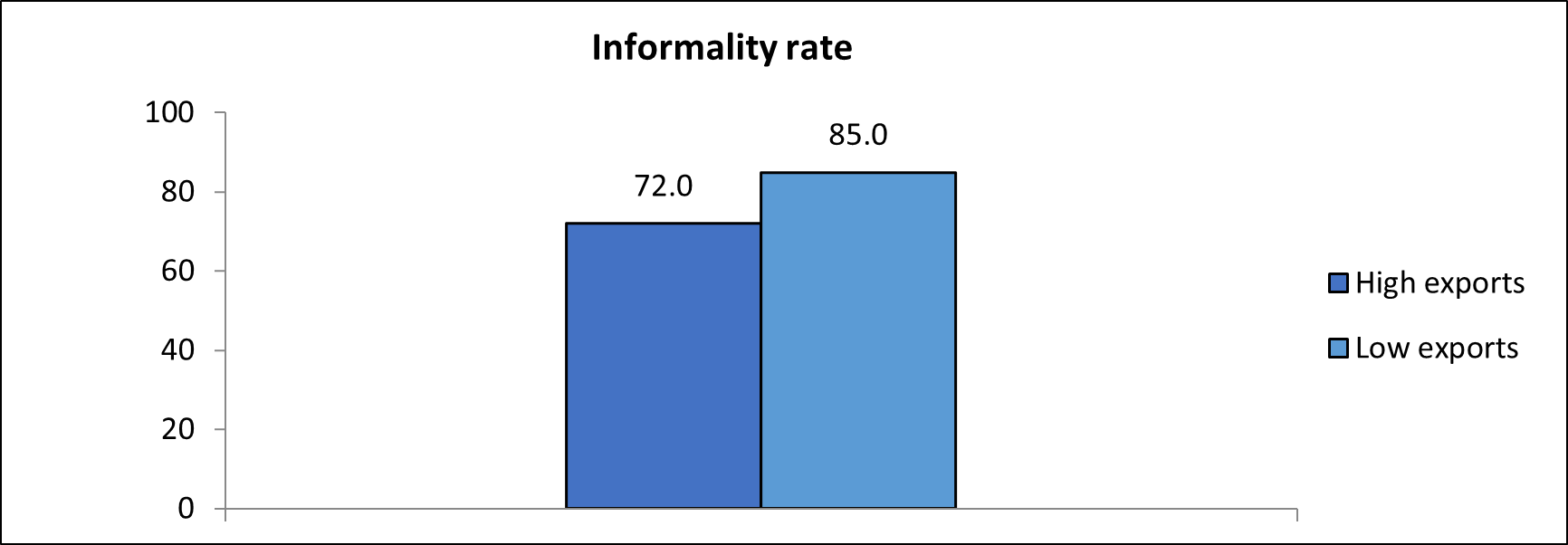

We find that the percentage of employees without pension or retirement benefits is lower in municipalities with high exports per worker relative to municipalities with low exports (Figure 2). Results suggest that the expansion in exports per worker significantly lowered the informality rate, even when isolating the impact of trade from a region’s proportion of rural population, literacy rate, population size, and the share of employment in the primary, secondary and tertiary sectors. Similar evidence has been found for Bangladesh, India, and Sri Lanka.

Figure 2: Exports can bring job security and benefits

(Informality rate across Mexican municipalities, by export level)

Notes: (1) The sample is restricted to the urban and semi-urban municipalities with complete data in the whole period. (2) A municipality has relatively high exports if the ratio of 2015 exports per worker in 2000 is above the median across municipalities and low exports if its ratio lies below the median. (3) Labor informality rate is measured as the percentage of employees without pension or retirement benefits at work.

This is good news for development because lower informality rates mean reduced vulnerability of workers. Informal workers usually include the self-employed (think for example of street vendors) and unpaid family workers. They often face poor working conditions, have no access to health or retirement benefits, and are more likely to be exposed to occupational safety and health hazards as well as extortion, bribery, repression, and harassment. They are also less likely to be organized, further undermining their vulnerable position. In contrast, workers in formal employer-employee relationships typically have higher incomes, more legal and social protection, security, and a voice.

Policy makes a difference

Let’s look at how some local policies shape the impact of export growth on local labor market outcomes in Mexico. In our analysis, we focus on the role of labor market flexibility, spending on education, and connectivity.

- Labor market flexibility: In places with more labor-market flexibility, an increase in trade brings more workers into the formal labor market and attracts more migrants (adjustment through worker movement). By contrast, in places with low labor-market flexibility, total wages are more likely to rise (adjustment through prices).

- Spending on education: Regions where spending per enrolled student is higher (at the federal, state and municipal levels) see gains in total labor incomes, implying a higher skill level of the workforce. Regions with lower spending on education, on the other hand, benefit from higher employment and reduced informality rates, as well as domestic migration of workers from other regions (which is dominated by unskilled workers).

- Connectivity: Faster access to local markets has a direct positive impact on local employment. Our findings suggest that higher imports per worker raise total labor incomes and the number of immigrants more strongly in regions with more extensive initial road networks. This can be linked to trade in global value chains dictating timely and reliable delivery of imported inputs to be used in export production.

What are some key takeaways of our study? First, the effects of trade on local labor markets are nuanced and depend on the labor market channels, the nature of trade, geography, the sector of employment, and local policies. Any attempt by policy makers to address market failures should therefore consider the specific context. Second, our findings suggest that in Mexico, workers adjusted to growing exports through movement from the informal to the formal labor market rather than increases in average salaries or incomes.

Join the Conversation