All over the world, there is growing evidence showing that women and men travel differently. While there are many reasons behind this, one key factor is the persistence of traditional gender norms and roles that translate into different household responsibilities, different work schedules, and, ultimately, different mobility needs. Greater overall risk aversion and sensitivity to safety issues also play an important role in how women get around. Yet gender often remains an afterthought in the transport sector, meaning most policies or infrastructure investment plans are not designed to take into account the specific mobility needs of women.

The good news is that big data can help change that. In a recent study, the World Bank Transport team combined several data sources to analyze how women travel around the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area (AMBA), including mobile phone signal data, congestion data from Waze, public transport smart card data, and data from a survey implemented by the team in early 2022 with over 20,300 car and motorcycle users.

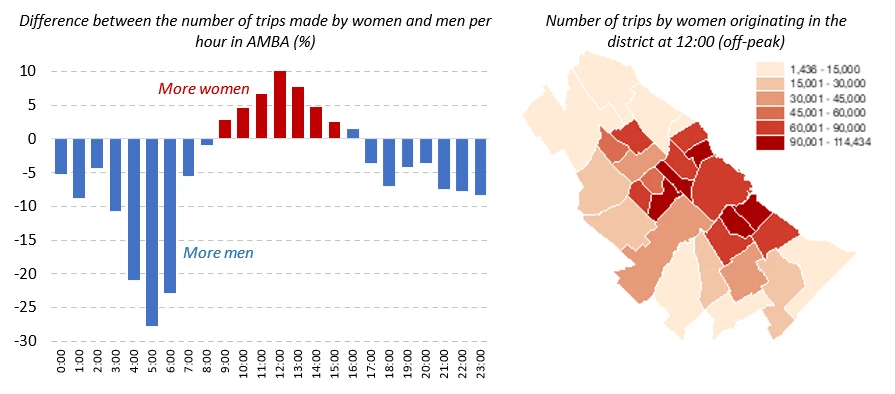

Our research revealed that, on average, women in AMBA travel less often than men, travel shorter distances, and tend to engage in more complex trips with multiple stops and purposes. On average, 65 percent of the trips made by women are shorter than 5 kilometers, compared to 60 percent among men. Also, women’s hourly travel patterns are different, with 10 percent more trips than men during the mid-day off-peak hour, mostly originating in central AMBA. This reflects the larger burden of household responsibilities faced by women – such as picking children up from school – and the fact that women tend to work more irregular hours.

Cycling and walking

Women in AMBA tend to make 7 percent more non-motorized (NMT) trips than men, and non-motorized transport account for 19.7 percent of their total trips compared to 18.0 percent for men. Generally, women’s decision to cycle is heavily influenced by the existence (or the absence) of proper cycling infrastructure. In AMBA, women’s non-motorized travel is highly concentrated in the City of Buenos Aires, where a growing network of dedicated cycle-lanes and the development of the Ecobici bikeshare system have made cycling a lot more appealing and accessible. The responses to the survey implemented by the study team with current car and motorcycle users suggest that the share of women who would consider using a safe cycleway for their typical trips instead of a motor vehicle is much higher (43 percent) than the share of men (26 percent). Data collected by the Secretariat of Transport and Public Works, confirm that women are eager to embrace cycling when the right infrastructure is there: with the exponential development of the cycleway network, the share of women among cyclists in the City of Buenos Aires reached 21.3 percent in 2019 compared to just 7.2 percent a decade earlier.

Public transport

Women in AMBA make 13 percent more trips by public transport than men, and public transport accounts for 21.7 percent of women’s total trip count compared to 18.6 percent of men’s. Women tend to use public transport more in districts with frequent service. Previous research also suggests that, in parts of the city, concerns over personal safety can deter many women from using public transport.

The impact of COVID-19

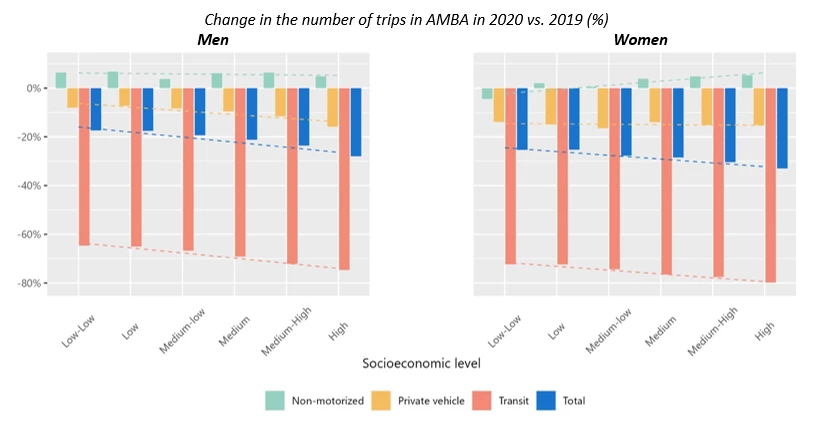

With the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, women reduced their travel more than men. This was partly due to greater reliance on public transport, which operated with reduced service for several months. Also, according to the findings of the survey implemented by the study team, the risk of COVID-19 infection – associated with public spaces, including public transport – was much more important in driving women’s travel choices, with over 40 percent of women naming it the single most important factor, compared to 32 percent of men.

The decline in public transport use was particularly steep among higher-income women, who typically enjoyed greater job flexibility and were better positioned to reduce their travel. Compared to lower-income women and to men, more high-income women were able to shift to walking and cycling. That is because high-income women tend to live in areas with better non-motorized transport infrastructure, and because their travel distances decreased more significantly than other groups during the pandemic.

Working toward inclusive transport

Based on these findings, an increased focus on micro-mobility and safe cycling infrastructure in AMBA would bring substantial mobility benefits for women, whose trips are generally shorter. Public transport schedules should also be adapted to accommodate women’s greater travel demand at off-peak hours. As we strive to build more inclusive cities, big data can go a long way in helping planners look at transport through a gender lens—and ensuring they design mobility solutions that reflect the needs of all users.

Join the Conversation