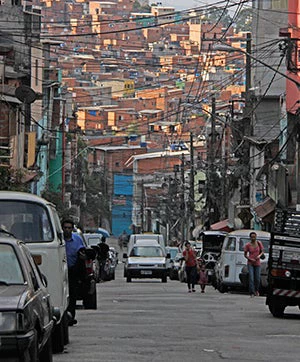

As we continue our efforts to increase awareness around on-foot mobility (see previous blog), today, I would like to highlight a project we developed for Paraisópolis.

While most of the community has access to basic services and there are opportunities for professional enhancement and cultural activities, mobility and access to jobs remains a challenge. The current inequitable distribution of public space in the community prioritizes private cars versus transit and non-motorized transport. This contributes to severe congestion and reduced transit travel speed; buses had to be reallocated to neighboring streets because they were always stuck in traffic. Pedestrians are always at danger of being hit by a vehicle or falling on the barely-existent sidewalks, and emergency vehicles have no chance of getting into the community if needed. For example, in the last year there were three fire events—a common hazard in such communities—affecting hundreds of homes, yet the emergency trucks could not come in to respond on time because of cars blocking the passage. To address some of these issues, our team partnered with LabGEO (Geoprocessing Lab of the University of São Paulo) to carry out an in-depth mobility diagnosis, with funds from ESMAP through the Brazil Energy Efficient Cities Program - Transport Component. The study was conducted in close cooperation with the community and drew on data from a wide range of sources, including:

- Traditional paper and pen Origin-Destination Survey (OD);

- GPS data on bus locations;

- Farecard data provided by the local bus company;

- Call data records from telephone companies;

- Georeferenced road collisions data from Sao Paulo’s traffic engineering company (CET);

- A detailed travel diary based on smartphone data application, an effort also financed by this project.

From these analyses, several important issues emerged. For instance, with the bus GPS and Farecard Data, we identified the number of people from the community using public transportation, their travel times, and their destinations. From these data sources, we also found that, although the average travel time by transit is shorter than in other low-income communities in São Paulo, the unpredictability of travel time is much higher. Unreliable transport forces commuters to add a safety margin, meaning they have to leave home early to make sure they can get to work on time, which takes away from the time they would spend with family, or engaging in leisure and educational activities.

Thanks to modern data collection and analysis, we now have further evidence showing that this type of urban development does not align with the mobility needs of low-income communities such as Paraisópolis. Let’s hope these findings can be an eye-opener for car-centric São Paulo, and can encourage planners and decision-makers to prioritize pedestrian-friendly and sustainable public transport designs.

The team is now dissecting the data, comparing the data sets, and striving to answer some key questions. For example, given the financial cost of acquiring these datasets, which ones should we prioritize to continue our work? When is the GPS and Farecard Data (normally available in more modern bus systems) a good representation of mobility constraints, and what can it tell us exactly? Is CDR data detecting walk trips as well as other sources? What is the potential of Smartphone Data collection and how to take advantage of this new technology?

As this work moves forward, we intend to take full advantage of technology and big data to gain better insights into the reality of urban mobility, and, more importantly, use that new evidence to propose concrete action. The information we generated also informs other operations, such as the SP Metro Lines, and we expect that this work can help improve the methodology of slum upgrading plans as well by including more mobility data.

Oh, did I mention that Paraisópolis was the theme of a soap opera in Brazil (I ♥ Paraisópolis)? But that is another story…

Join the Conversation