Would you apply to a job if you knew your gender was not welcome?

Discriminatory hiring practices are damaging. They discourage employment, reduce productivity, and otherwise prevent people from reaching their full potential. In our recent paper, we studied the extent of gender discrimination using an experiment that randomly assigned fictitious resumes to job advertisements in Uzbekistan. The qualifications, experience, and other details for each resume were identical – except for a single detail. Half of the applications used a woman’s name, and half a man’s name.

This seemingly tiny discrepancy makes all the difference.

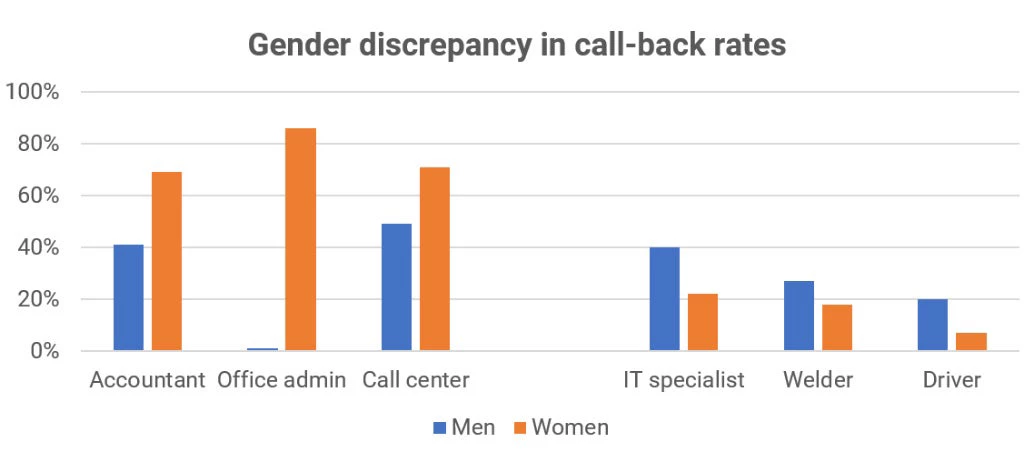

The fictious applicant’s gender dramatically swings the odds that an application receives a response. After tallying the results, we found that for a woman to get a call back for a job as a driver she would have to submit 180% more applications than a man with identical qualifications. For a man to get an interview as an accountant, he would have to send 79% more applications than a woman candidate, and for an office manager job as many as 685% more applications.

But despite these large effects, by the time the results came in they were no surprise. As we prepared the study, we found many instances of overt discriminatory selection criteria. Prospective employers often included age, gender, and appearance requirements in the job announcements we randomly applied to. For example:

- For secretarial positions announcements we reviewed, about 68% contained gender requirements, 72% included age requirements, and 22% appearance requirements.

- For accountant positions, 42% included gender requirements and 46% included age requirements.

- About 27% of call center operator announcements contained gender requirements and 28% included age requirements.

- Though there were usually no explicit gender requirements in vacancy announcements for more male-dominated occupations (including IT specialists, welders, and drivers), the wording in Uzbek and Russian commonly referred to applicants as “he,” “him” or “guys.”

As in many countries, Uzbekistan’s laws guarantee equal rights and opportunities for men and women. Nonetheless, women in Uzbekistan are underrepresented or have secondary roles in many high-paying fields including science, technology, engineering, and mathematics . Men are also strongly underrepresented in certain roles, especially in health and education services where women held more than three-quarters of jobs in 2021. Occupational segregation is one of the core drivers of Uzbekistan’s gender wage gap, where pay among working women is about 39% less than men’s pay on average, according to government statistics. Our findings suggest this is due at least in part to prejudice and discriminatory norms. Even if there were no other forms of gender discrimination in the labor market, these biases alone are enough to strongly segment the labor market into “men’s jobs” and “women’s jobs” in Uzbekistan.

The patterns we find may contribute to other gender disparities in the labor market as well. The female labor force participation rate has remained consistently much lower than among men in Uzbekistan, by as much as 28 percentage points according to the World Bank’s Listening to Citizens of Uzbekistan survey. Women are also more likely to be unemployed, suggesting that when looking for work, women have more difficulty finding a job than men do. In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, the official unemployment rate stood at 13% for women compared to just 6% for men.

But the good news is that these challenges are amenable to reform. Many countries have made swift progress through such legal reforms punishing discriminatory practices and developing mentoring, scholarship, and training programs to close gender gaps. Uzbekistan’s government has been highly proactive in this regard. Discrimination in hiring practices is expressly prohibited in Uzbekistan’s new labor code that is expected to come into force soon, and a range of programs to address gender imbalances were announced in the new national development strategy in 2022.

These are auspicious changes for Uzbekistan that have significant economic and social implications. A large literature attests to the benefits of occupational integration for both sexes and the large contributions addressing discrimination can have for human capital accumulation and firm productivity. Providing equal opportunities for both men and women in nontraditional occupations can lead to better job matching, a more productive labor force, and higher incomes.

For Uzbekistan and beyond, addressing unfair treatment in the labor market is essential part of generating more rapid and inclusive economic growth.

Join the Conversation