Regional differences are significant not only in Russia and approaches like the one used by the colleagues behind the BEEPS are mushrooming. Here are three examples that piqued my interest because of their usefulness for policy making.

Global Integrity began collecting sub-national level data on corruption risk in 2010 for various countries and completed a project on assessing corruption risk in all fifty US states with the Center for Public Integrity and Public Radio International in 2012. An interesting and sobering reading for any of us interested in good governance and corruption. And a very powerful tool for citizens and policy makers to increase accountability and reduce corruption risks.

The Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) Initiative, launched in 2009, has recently completed its third round, collecting data from more than 13,000 citizens from 63 provinces. Such disaggregated data (on participation, transparency, accountability, control of corruption, public administration and service delivery) can be used as a tool to monitor reform progress and as an input for policy making.

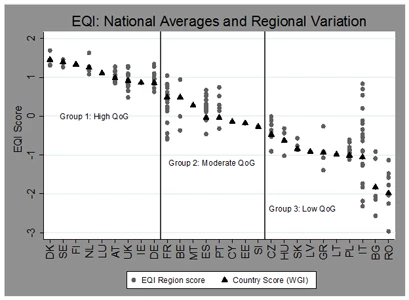

The Quality of Government Institute in Gothenburg has just released new data that documents the existence of significant regional differences in term of corruption in Europe. Using an approach similar to the BEEPS, the Gothenburg colleagues have collected data from citizens on quality of institutions and extent of corruption at the regional level. Figure 1 above shows the data on quality of government, unbundled by region.

When I first saw this data a few weeks ago I was struck by a simple realization: national plans to address poor governance and corruption suddenly appeared meaningless in countries like Italy, Belgium, and Romania where the data shows significant regional differences. And, a more profound understanding of the possible reasons behind such in-country variation became the key question to address for policy purpose.

The story, however, does not stop here and we can now document another important type of variation when it comes to corruption and quality of institutions -- one that manifests itself across different public agencies within the same country.

Consider for example the data collected through the Governance and Anti-corruption Surveys (interviewing citizens, business people and civil servants add website link) from countries in Africa and Latin America. The data, originally collected to support individual governments in their effort to design a national anti-corruption strategy, suddenly offered a new insight on the phenomenon of corruption thanks to the information we gathered from civil servants.

Looking at aggregate indices of corruption available for these countries, we observe that their values are quite similar at the time of the survey, making us think that the phenomenon of corruption (and the potential policy tools to address it) could be "comparable" across these countries.

Moreover, talking with business people, citizens and civil servants allow us to ask about different types of corruption and to study their distribution across regions, displaying interesting differences in terms of the types of corruption, as the BEEPS have shown for the Russian Federation.

While pulling together the data for a research project, however, I stumbled on something unexpected. The responses of civil servants could be aggregated along a novel dimension: the public agency where the civil servants worked.

This “agency-level” variation forces us to look at corruption in a new way and forces us to reevaluate the tools that can be used to address it. Initial work suggests that policy tools like internal audit mechanisms, the sharing of information with the public about the agency’s activities, and a merit based system for staff can reduce the risk of corruption at the agency level. But more work is needed and additional data from a larger and more diverse group of countries need to be collected.

For the ones, like myself working in this field, this growing body of evidence suggests that what had been long thought of as a homogenous phenomenon, now appears to be -- at the very least -- a three dimensional issue, varying in terms of type, across regions, and across public agencies.

More importantly, for practitioners like myself, the data tells us that a solution to address this problem may be found by understanding why some public agencies display lower levels of corruption and better institutions and why others do not, and identifying their agency-specific organizational incentives.

Join the Conversation