Governments around the world face a lot of pressure to do something to help jobseekers. In a new paper forthcoming in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, we examine new evidence and innovations in how job training and job search programs are being designed and implemented. Today’s post focuses on what we have learned about job training, while a second post will look at job search and intermediation programs.

The big concerns with government-run programs

Previous reviews and studies of vocational training programs run by governments offer plenty of reasons to be skeptical about such programs. Many public sector training agencies appear to be not very nimble, reward inputs (numbers trained) rather than outcomes (jobs achieved), and have limited linkages to the private sector. The result is often training programs that may be of low quality and teach skills that are not necessarily in high demand. Many of the first generation of impact evaluations of these programs found limited impacts, with David concluding in a 2017 review that typically only 2 or 3 people out of every 100 trained would find work as a result, while Blattman and Ralston (2015) argued that “it is hard to find a skills training program that passes a simple cost-benefit test”.

The renewed rationale for government involvement

Nevertheless, we see several reasons why there is continued or renewed interest in government support in providing skill training to workers.

1. Structural transformation and the Green Transition: Changes in the structure of the economy with globalization, automation, and desire for a green transition may require workers to have different skills from those they currently have. Liquidity constraints and inefficiencies in the private training market may make it difficult for workers to learn these on their own, and perhaps governments may be able to speed up the reallocation of labor by helping workers re- and upskill.

2. Increasing empirical evidence that firms may underinvest in training workers because of fears they may leave for other jobs. For example, recent studies have found evidence for this in Colombia and Ghana.

3. Renewed interest in industrial policy also may lead to arguments that coordinated investment in some specific technological or sectorial-specific skills is needed as part of a strategy to attract large multinational companies that create many jobs and have spillover benefits for the broader economy.

4. Finally, increased attention to equity and inclusion may be used to justify a focus on training particularly disadvantaged groups, even if this does not increase the total number of jobs.

What do impact evaluations now tell us about the effectiveness of such programs?

The last few years have seen more impact evaluations of vocational training programs run by both governments and NGOs. In a forthcoming handbook chapter, Agarwal and Mani include an additional 14 recent studies from the 9 David surveyed in his review, and do a formal meta-analysis. They find an average impact on employment of 4 percentage points (with a 95 percent confidence interval between 2 to 6 percentage points) and on earnings of 8.2 percent (with a 95 confidence interval between 2 to 14 percent). These impacts on employment are similar in magnitude to the average impact of training in high-income countries in Card et al. (2018).

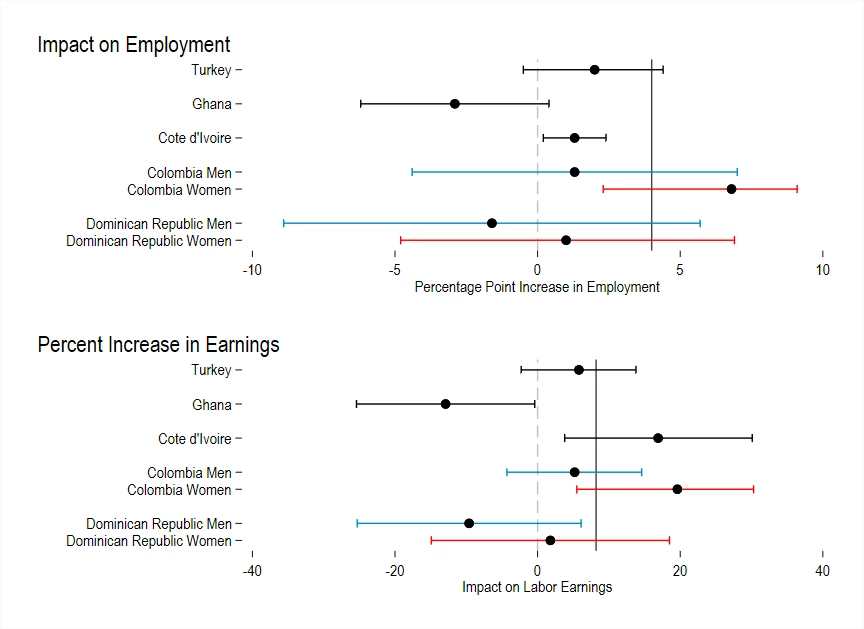

However, some of the largest effect sizes have been found in small-scale studies, often of programs run by NGOs. Figure 1 below, taken from our paper, compares these meta-analysis methods (the vertical lines) with the individual estimates from the five experimental evaluations that we could find of government vocational training programs that trained at least 5,000 people in a year. The estimates tend to be lower than the meta-analysis averages, reflecting the greater difficulty in achieving value for money when such programs are implemented at scale. There is even the possibility of negative effects, if jobseekers are trained in areas that are not that highly demand, lose time out of the labor force, and then have unrealistic expectations about how much they should earn afterwards and only search for jobs in the areas in which they are trained.

Figure 1: Limited Effects of Large-Scale Government Job Training Programs on Employment and Earnings

We continually hear about the need to improve the effectiveness of such programs by making the content more demand-driven, and delivered by private sector providers instead of bureaucratic government training institutes; as well as by innovations such as results-based contracting in which some of the payments to providers are conditioned on outcomes. These are promising in theory, but many governments lack the capacity to measure results and manage such processes well, and there can be many implementation challenges, as discussed here.

Some of the more promising results come from programs implemented by NGOs such as BRAC. As Orianna Bandiera mentioned in her recent Development Impact interview, BRAC sees impact evaluation as a core part of program implementation, something that is rare for governments. In work in Uganda with BRAC, Alfonsi et al. find six months of vocational training resulted in 9 percentage points higher employment and 25 percent higher incomes 3 years later, considerably higher than the average impacts in Figure 1 above.

These efforts definitely provide hope that job training can be done better. But as John List’s The Voltage Effect notes, there is a tendency of program impacts to fall with scale. It is difficult to maintain training quality and ensure topics meet the needs of employers when delivering training to tens or hundreds of thousands, and then general equilibrium effects may arise – where lots of new jobseekers all trained in the same skills compete with one another for a fixed supply of jobs. Secondly, we caution that what sound like impressive changes in earnings in percentage terms are often relative to very low bases, so that impacts need to last for very many months to pass cost-benefit tests. For example, the 25% increase in income in Alfonsi et al only equates to an extra $6.10 per month in earnings, for a program that costs $470 per person.

So where is the role for government?

Overall, the recent evidence offers some reasons to be a little more optimistic about some training programs than perhaps was the case 5-8 years ago. But also plenty of reasons for caution. First and foremost, the main jobs issue is typically one of too few employers with good job opportunities, and policies which only work on labor supply without supporting labor demand are likely to fail. Second, the related point is the need to ensure what is being taught is something that will be demanded in the market. Third, a key area for both policy improvement and for new research involves the appropriate targeting and selection of participants into these programs. Modest average impacts may mask large effects for certain subsets of jobseekers (and even negative effects for some others). Working to identify how to best match jobseekers to opportunities to build skills that best suit them is an area where much is still to be learned.

Join the Conversation