Understanding and addressing social norms is critical for more equitable gender outcomes for World Bank projects. Copyright: Dasan Bobo/World Bank

Understanding and addressing social norms is critical for more equitable gender outcomes for World Bank projects. Copyright: Dasan Bobo/World Bank

The draft World Bank Group Gender Strategy 2024-2030 identifies understanding and addressing social norms as critical for more equitable gender outcomes for Bank projects. A new Thematic Note on Addressing Social and Gender Norms to Promote Gender Equality builds on work from the World Bank and beyond to provide guidance for policy practitioners worldwide on how to better understand, measure, and – where possible – change social norms for more gender equitable development outcomes, ensuring societies and economies reach their full potential.

So, what is a social norm?

Social norms are part of the social cues that guide our behavior and expectations about what should or should not be done in a given social setting. We follow these rules because we see others around us following them (and if we don’t see them, we expect others are following them) and believe other people expect us to follow them. Social norms are distinct from other drivers of behaviors – laws, morals, customs, or individual attitudes – because they are held in place by these interdependent expectations, and we expect social sanctions (gossip, isolation, physical harm, and others) if we don’t conform to expected behaviors. As such, some social norms support the perpetuation of unequal gender outcomes such as differences in economic participation, gender-based violence (GBV), sexual and reproductive health, and representation in political bodies.

How can we measure social norms, and why does it matter?

Up until recently, social norms have been most commonly observed in three ways: by looking at the outcomes that are assumed to be strongly dependent on social norms (e.g., child marriage or women’s employment); by looking at the individual attitudes or opinions that express commonly held views (e.g. who should have priority for a job); or by looking at the presence or absence of specific legal norms or policies (e.g., parental leave policies). However, all these measures are only partial reflections of a social norm. A law can be in place but not be enforced, a personal attitude may be private and not translate into a behavior, and so forth.

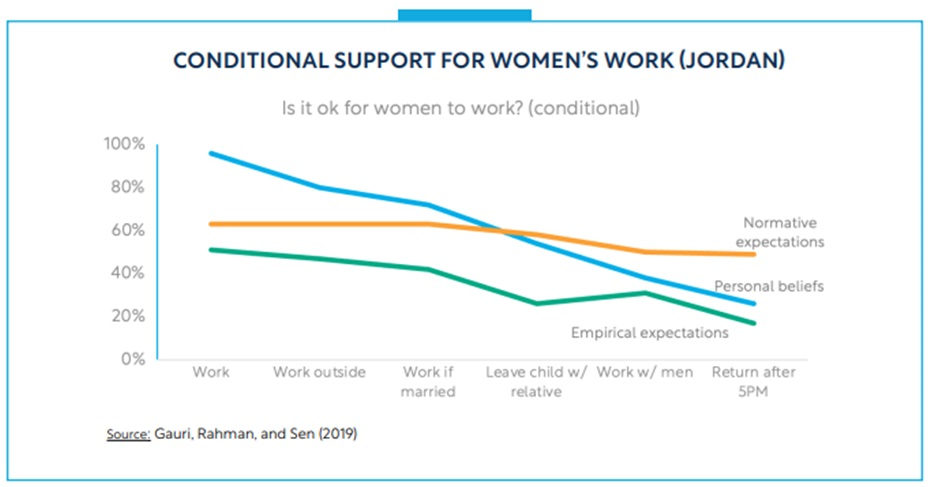

Direct measures of social norms ask people about all aspects that make a norm: what they do and believe (personal beliefs), how common it is for others in their social group to exhibit a behavior (empirical expectations), whether the behavior is socially acceptable (normative expectations), and the consequences of engaging in the behavior. People are more likely to adhere to a norm if they perceive that others do as well, and they are more likely to adhere to a norm if not doing so triggers some sort of punishment. For instance, a survey on social norms shows that there is high support for women working in Jordan, but support declines depending on the specific conditions of such work, such as women coming home late or working with men (see figure below).

Measurement of these social expectations and personal beliefs can help to better determine what type of policy interventions are appropriate.

Policy design to shape social norms

An intervention to address a social norm should be developed based on how deeply engrained the norm is within a given society as well as the mechanisms that allow the norm to persist. The relationship between the two interdependent elements—what others do and what I believe others believe—can help identify the barriers to social norms transmission. This relationship can take the form of an S-curve.

When a norm is widely prevalent and deeply internalized, strong barriers such as internalized personal identities can sustain them; for example, masculinity norms that are strongly linked to men’s identities. Programs such as Equimundo’s Program H works with men to redefine aspects of what is seen as part of ‘being a man’ and by doing so, changing traditional masculinity norms through a combination of school curricula and community campaigns.

Once a new norm starts being adopted, the process can accelerate and reach a tipping point where social incentives can propel rapid change. For example, personal beliefs can change, but people may not change their behavior due to incorrect assumptions about others’ actions and approval. This is referred to as pluralistic ignorance, and it can be addressed by simple interventions that provide information about other people’s “invisible” beliefs, as in Saudi Arabia, where disclosing private information to married men about views supportive of women’s employment held by other married men increased the former group’s willingness to encourage their wives to work.

Even when there is widespread acceptance, last mile challenges can remain, especially with groups that are most resistant to change. Legal changes or increased enforcement of legal frameworks can help at this stage, as was the case with same sex marriage in the United States.

Social norms interventions are not standalone solutions; they require both direct and indirect policy tools and interventions (as seen in the figure below). While the former tend to address structural and environmental factors that reinforce unequal norms and create the conditions for norm change to happen, the latter can change fundamentally the underlying beliefs and values that support unequal social norms.

How can development practitioners approach gender norms change?

The mechanisms through which social norms impact gender equality outcomes may be complex, involve multiple actors at various levels (households, communities, societies), and operate differently depending on women’s opportunities, agency, and constraints. In many cases a complete norm change might take time that goes beyond the lifetime of a program or project.

In the note, we make the case for a shift towards greater norms awareness in all projects. Norms-blind policies ignore the presence and role of social norms, which can cause them either to fail in achieving their objectives or to reinforce existing norms and gender inequality. Increasing norms awareness means for all to ask themselves whether social norms might play a role in their project, and for projects where norms appear to be an important barrier to achieving their desired outcomes, to design ‘norms-sensitive’ interventions, and to seize opportunities to design and implement ‘norms transformative’ interventions. In practice, this means paying attention to the existing norms and how they might impact how activities are implemented, their effectiveness, and who will benefit from them. When feasible, development practitioners should design interventions to address the factors that reinforce these norms, and support the creation of new positive norms for greater equality gains.

To receive weekly articles, sign-up here

Join the Conversation