This blog is part of the series "Small changes, big impacts: applying #behavioralscience into development".

While Latin America is rich in water, people’s ability to access safe, reliable water supply remains elusive in most countries. Worse, most countries and major cities in the region will face economic water scarcity in less than a decade. Strategies to manage water scarcity vary, from investing in water recycling facilities to changing consumer behavior.

The most common ways to change consumer behavior are to increase the price or conduct communication campaigns to encourage conservation. Neither solution, however, is guaranteed to succeed. In some cases, they even backfire. Increasing price, for example, can upset citizens who currently pay little for poor quality water. Likewise, if done poorly, communication campaigns can cause panic and increase consumption and water stockpiling, something Bogota faced in 1997 when a tunnel providing water to the city collapsed and caused water shortages.

The World Bank’s World Development Report 2015: Mind, Behavior and Society detailed the creative actions city officials took in Bogota to address the negative unintended consequence of its initial communication campaign. To improve its communication, the city:

- provided stickers featuring a picture of the statue of San Rafael (which was the name of the emergency reservoir the city was relying on)

- published daily reports of the city’s water consumption in the country’s prominent newspapers

- engaged in entertaining campaigns illustrating the most effective ways to conserve water such as a TV ad with the mayor showering with his wife

- published names of households that were not cooperating, and rewarding those who were

- imposed minor sanctions against businesses with the highest level of consumption

Today, the interventions used by the city of Bogota would be known as ‘nudges’: small interventions to promote behavior change through the application of insights from behavioral economics. Unlike more traditional economic theory, behavioral economics does not start with the assumption that people are perfectly informed, own-payoff maximizers. Instead, it views people as imperfectly informed decision-makers whose rationality has bounds and who are motivated by both private and other preferences.

With this perspective, behavioral economics points to alternative approaches to environmental protection that can complement, or substitute for, more traditional approaches. Behavioral approaches to environmental protection aim to change the framing and thus the perceived context of choices in a way that highlights the implications of choices, which would otherwise be obscured by automatic thinking. In other words, they help make it easier for people to make better choices — better for themselves and for society.

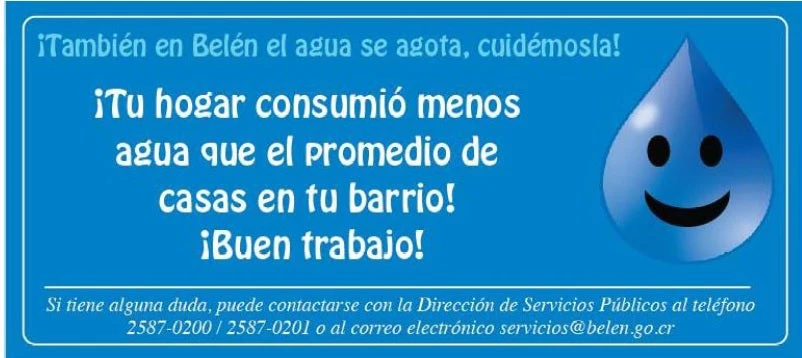

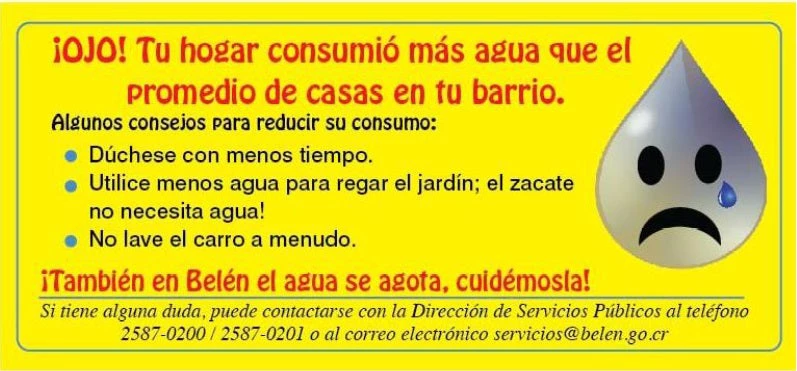

In developed countries, there is strong evidence that persuasive messages have reduced water consumption and energy use in an economically meaningful way. Although these studies differ in terms of location and the content of the messages, they have found that pro-social messages with social comparisons (where your usage is compared to others) reduce consumption substantially both in the short and long-term.

In the water context, for example, a norm-based message was tested in a randomized controlled trial during a drought in a southern US state. Residential households that were exposed to a one-time message aimed at nudging them to use less water used less water than a control group that received no such message — by almost 5 percent in the first year after the message was sent, and by almost 2 percent in the third year. Interestingly, the estimated 5 percent reduction is equivalent to that which would be expected if average prices were to increase approximately 12 to 15 percent. Given that public utilities are often strongly regulated, it is difficult to increase price beyond cost recovery (in other words, to cover both delivery costs and scarcity costs). Therefore, behavioral approaches provide a (new) set of complementary and effective policies for conservation.

Can such a nudge solve water scarcity problems in drought-prone areas? Possibly no, but it’s a contribution to the solution — and a relatively inexpensive one. For the water system in the study, the intervention cost was only $0.37 per 1000 gallons saved in the first three years after the messages were sent.

Although more investigation is needed on the power of norm-based messages in developing countries, other randomized controlled trials found similar impacts. A pro-social message with social comparison in Colombia found a reduction of nearly 7 percent, while in Costa Rica the reduction was between 4-6 percent.

Furthermore, the experimental results highlighted something about the equity implications of the behavioral impact: the burden of water reduction was largely shouldered by high-income households rather than poorer ones. Previous research has found that high-income households in urban areas are less price-sensitive to changes in residential water prices, so the norm-based messages may be complementary to price-based policies. The power of norm-based messaging has also been observed in other environmental contexts, such as recycling and compliance with national park laws.

Several heads of state have called for a fundamental shift in the way the world looks at water to ensure a water-secure future for everyone. This opens the door for high level political support for new types of approaches, including those that help change perceptions, behavior, and norms related to water.

And while behavioral nudges alone are not going to solve the global problems of ecosystem conservation, pollution reduction, climate change mitigation and poverty alleviation, they can help contribute cost-effectively to the solutions. Importantly, they typically require no new laws to be implemented. Environmental scientists and practitioners should take a closer look at them — and make more attempts to integrate experimental tests of their effects into the implementation of conservation programs.

As the World Bank, governments, and partners continue experimenting and applying behavioral science in government programs and policies, we will share with you through this series ‘Small changes, big impacts: applying #behavioralscience into development’, the latest development and thinking in the region. Join us and share your thoughts, your work and thinking.

Previous post in the series: Public policy with a true human face

Interested on Behavioral Economics? Sign in and we will keep you posted of all latest news in the topic.

Join the Conversation