Dos mujeres en un laboratorio de la comunidad San Juan Cuauhtémoc, México.

Dos mujeres en un laboratorio de la comunidad San Juan Cuauhtémoc, México.

Women in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have different economic opportunities than men. This may not be surprising news for most readers. In this blog post we discuss two less explored facets of this issue.

Poverty is not gender neutral

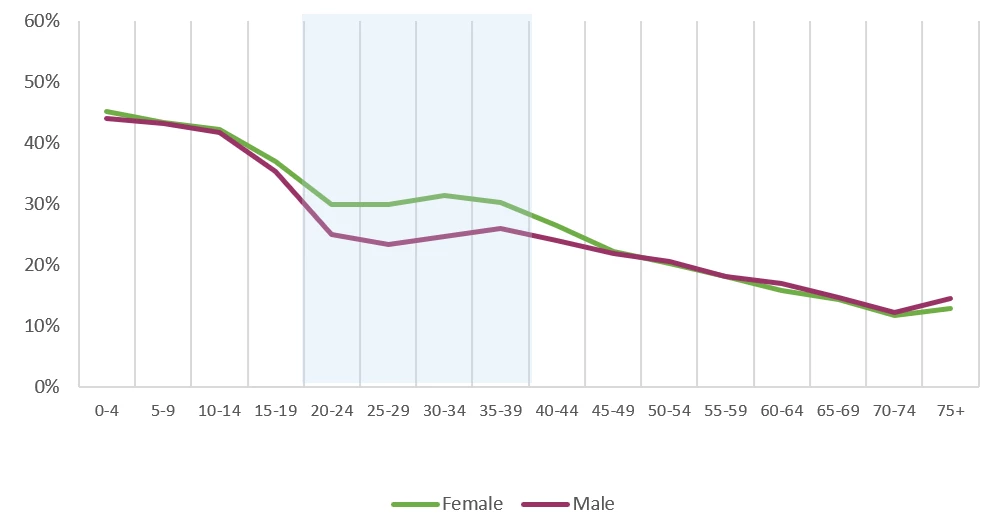

During the life cycle, poverty among men and women evolves differently. As individuals enter productive ages, poverty drops, but it does so at a faster rate for men than for women. This “female poverty penalty” during some of the most productive and fertile years of peoples’ lives is high in Latin America and the Caribbean compared to most other regions . At its peak, it reaches seven percentage points for individuals aged 25-35. Later in life, the gender poverty gap vanishes again. The most worrisome part of this news: this gap has been increasing over the last 15 years.

Female and male poverty rates diverge around fertile ages in Latin America and the Caribbean

(Poverty at USD 6.85 per day 2017 Purchasing Power Parity)

Why is this happening? Researchers have found explanations in labor market outcomes:

- Women are nearly five times more likely than men to be out of the labor force (32 vs. 7 percent).

- When employed, women are more likely to work in part-time jobs

- Gender segregation in occupations is common and has not changed much during many decades

- Women experience glass ceilings in their career trajectories. As a result, in LAC the aggregate amount of labor income women generate is about half of that of men.

The reasons behind these poor labor market outcomes are diverse, but new explanations have emerged from a line of work that 2023 Nobel laureate Claudia Golding opened: unequally distributed caregiving duties and lack of alternative care services. And there is a segment of the population that deserves special attention.

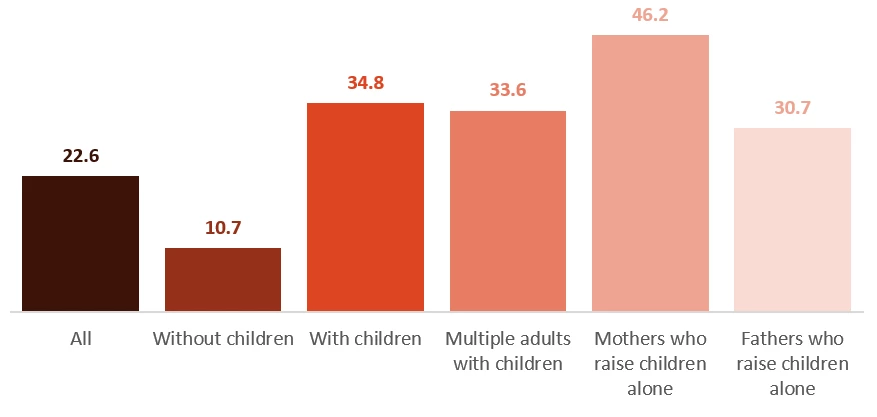

Women who raise children alone

Households where only one adult woman cares for one or more children are rising. They moved from 7.8 percent of all households with children in 2007 to 9.8 percent in 2021, higher than the global average. These women are exceptionally labor-constrained, and this is reflected in their income. Households with one woman raising children alone have a total income of USD 8.4 per person a day, significantly less than the USD 14.9 of the average Latin America and the Caribbean household . Accordingly, poverty incidence among these households is more than double that for the region overall.

Mothers who raise children alone are highly likely to be poor in Latin America and the Caribbean

(Poverty at USD 6.85 per day 2017 Purchasing Power Parity)

Household Poverty Rate, 2021 %

What can we do?

A focus on increasing female labor force participation (FLFP) and closing earning gaps is key. Effective evidence-backed policy options include: providing childcare services, disseminating information on work opportunities and returns to employment, training in socio-emotional skills, addressing norms by engaging partners and family members, and targeting women via social protection, safety nets, and public-works programs.

Expanding access to affordable and quality care is clearly of vital importance. In Rio de Janeiro, a program that expanded access to free publicly provided childcare to families living in the city’s low-income neighborhoods resulted in a 10 percent increase in mothers’ employment (from 36 percent to 46 percent).

Legal reforms are an essential pre-condition to fostering FLFP. They will be successful in helping women if they go hand-in-hand with other changes. Pairing parental leave with measures to expand childcare coverage, effective communication and socialization of such reforms proved to be a powerful combination. In Uruguay, the Latin America and the Caribbean Gender Innovation Lab (LACGIL) supported a study that experimentally identify the effectiveness of low-cost targeted information interventions: they increased knowledge about parental leave, and shifted traditional gender norms among mothers.

Recent decades have shown that rapid progress can be made. FLFP in LAC has increased over the last decades, leading to higher female labor earnings and a significant reduction in poverty between 2006 and 2016. Legal frameworks were strengthened in many LAC countries to protect women’s rights at work including protection against harassment, discrimination in employment, and paternity/parental leave. Yet, gender gaps persist. The new World Bank’s Gender Strategy proposes to focus on innovation, financing, and collective action in order to end gender-based violence, elevate human capital, expand and enable economic opportunities, and engage women as leaders.

The LACGIL within the Poverty and Equity Global Practice, works in partnership with units across the World Bank, aid agencies and donors, governments, non-governmental organizations, private sector firms, and academic researchers. This work has been funded in part by the World Bank Group's Umbrella Facility for Gender Equality (UFGE), a multi-donor trust fund administered by the World Bank to advance gender equality and women's empowerment through experimentation and knowledge creation to help governments and the private sector focus policy and programs on scalable solutions with sustainable outcomes. The UFGE is supported by generous contributions from Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Wellspring Philanthropic Fund.

Kelly Yelitza Montoya Munoz provided excellent research assistance.

Subscribe and receive a weekly article

Related articles

Join the Conversation