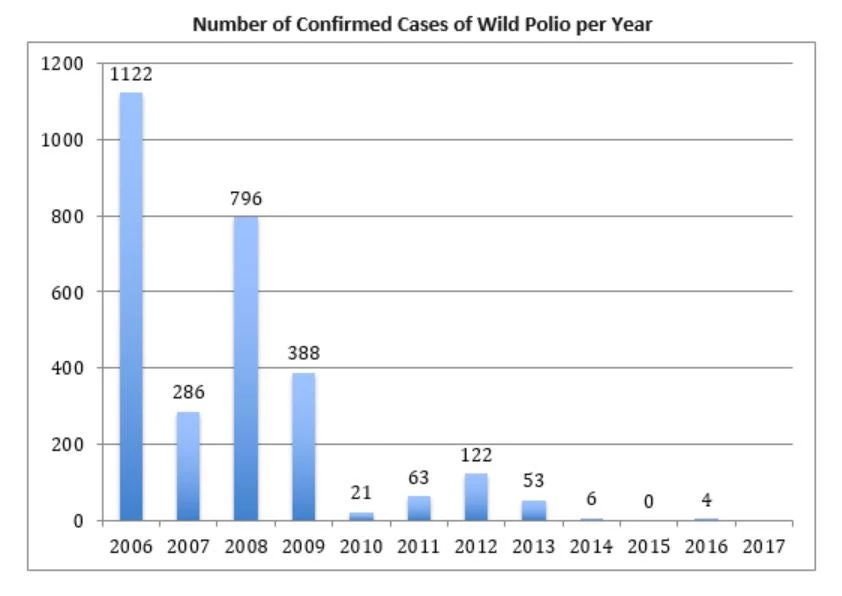

Many people were bitterly disappointed when four cases of wild polio were discovered in August 2016 in insecure areas of Borno State in the northeast of Nigeria. Nigeria had gone for almost two years without any cases of wild polio being detected, and was just a year away from being able to declare polio eradicated. (Wild polio is the type of the virus found in nature, as opposed to in a vaccine.)

The government’s response to the new cases was rapid, relentless, and effective. It made dramatic progress in controlling the outbreak, with support from the World Bank and other partners. There have been no wild polio cases since.

These efforts against polio are impressive given the fact that they were actively resisted by Boko Haram insurgents. In the past, Boko Haram has targeted vaccinators, killing nine of them in 2009 and three more in 2012. It has warned members of the population against accepting vaccination against polio. It has also destroyed roughly 35% of health facilities and damaged a further 10% in Borno, and more facilities in the bordering states of Yobe and Adamawa.

The insurgents have captured local government areas (LGAs), rendering them inaccessible to vaccinators and disease surveillance teams. But progress towards polio eradication was made despite the obstacles (see figure).

Response: The government’s response to the 2016 outbreak in Boko Haram-affected LGAs in Borno was swift and well-coordinated. The Minister of Health declared a public health emergency, and a multi-national, Lake Chad Basin Polio Task team—comprising Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad and Niger—was formed to coordinate its response.

Part of this response was a form of strategic stabilization; between January and December 2016, a mixture of civilians and a Nigerian Joint Military Task Force reduced the proportion of rural settlements that had been inaccessible to the Health Ministry from 61% to 39% in Borno State.

The government and its partners used other strategies, too, including:

- “Hit and run” involving a large team carrying out a rapid campaign in just a few hours, before insurgents even know vaccination is going on.

- “Fire walling” that involves vaccinating children along the borders of inaccessible LGAs, to prevent polio from spreading.

- “Transit teams” vaccinating children in markets, checkpoints, motor parks, nomadic camps, and on the borders to prevent transport routes from aiding the dispersal of the polio virus.

- Mobile outreach teams were deployed to hard-to-reach areas to vaccinate children as well as to vulnerable populations in under-served IDP camps and children from settlements recently retaken by the Nigerian military.

- Permanent health teams comprising community members dressed in normal clothes who went discreetly from house to house giving oral polio vaccines.

Evidence of Success

The use of these techniques resulted in measurable improvements in vaccination coverage. A series of rapid and small sample household surveys based on lot quality assurance sampling (LQAS) demonstrated that more than 80% of the LGAs in Borno and Yobe states achieved greater than 80% polio coverage in 2016.

The disease surveillance system has also improved. The number of reported Acute Flaccid Paralysis cases (that could be polio) increased by 71% and 46% between 2016 and 2015 in Borno and Yobe states respectively. Environmental sampling testing for the presence of wild polio virus has also demonstrated significantly less circulating polio virus.

Bank’s Role

In late 2015, the Government of Nigeria requested additional financing of US$125 million to support the polio eradication campaign. It was approved in less than 6 months and came at a critical time. Funds earmarked for procuring vaccine for 2017/2018 were used on an emergency basis to buy oral polio vaccine for the outbreak. If Bank funds had not been available, vaccines would have been nearly completely out of stock in Quarter 1 of 2017. This would have had a dreadful impact on the outbreak response and would have also impeded routine immunization.

Lessons

Lessons can be learned for other conflict-affected areas and for strengthening the health system:

- Relentless dedication: many motivated, courageous health workers and community members put themselves at risk to reach under-served children.

- Strong partnerships: the polio eradication program benefits from strong partnerships among countries and with the Government of Nigeria and development partners, such as the World Bank, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, USAID, Dfid, Rotary International, US-CDC, Canada, the Gavi Alliance, WHO, and UNICEF. The program also benefited from religious and traditional leaders who provided regular security updates to vaccination teams.

- Obsessive collection of data and its use: the polio program boasts a robust data management system staffed by highly qualified health workers who continuously monitor trends in OPV coverage, AFP epidemiology, and environmental surveillance. Having real time data has facilitated prompt, evidence-based decisions.

- Creativity and boldness: the outbreak in insecure areas necessitated a response that was “business unusual.” A willingness to take some risks was at the heart of its success.

Boko Haram has tried hard to obstruct polio eradication, but the campaign progressed anyway.

Join the Conversation