The World Bank has launched its first survey across South Asia to examine the coronavirus pandemic’s impact on jobs, health services, and social safety nets in the region that is home to 1.8 billion people.

The South Asia Region COVID-19 Rapid Monitoring Survey is interviewing a total of 43,000 respondents from all eight countries via their mobile phones to get a clear picture of how the pandemic is affecting jobs, what social assistance people are getting, and what measures would help them to cope with the pandemic. South Asia is made up of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

During a summer pilot survey, we tested questions, procedures, and quality control measures to ensure the survey produces reliable data that client countries can use for policies and programs related to jobs, safety nets, and healthcare. The survey consists of eight topics with questions ranging from “Are you getting the usual prices for your produce for this time of year?” to “When was the last time you worked for pay since January?” and “Based on your current financial situation, how long do you think your household will be able to eat and meet other basic needs?”

After collecting and analyzing the survey data, the Bank will release the findings this fall, by country. The results will document changes in South Asians’ livelihoods and incomes since the pandemic began. Questions included on the survey will capture how businesses are changing products or services and using specialized apps and digital platforms. In addition, the survey will show changes in the availability and price of common food items, satisfaction with health services received, concerns about access to food, and desired assistance from the government and other sources.

We organized the survey with help from Orange Door Research/GeoPoll and their partner institutions in the region. They are conducting the survey with country teams that vary in size from a half-dozen interviewers in Maldives, the region’s smallest country, to 45 in India, South Asia’s biggest country.

Avoiding lost in translation

The pilot survey generated valuable insights about organizing and managing a large-scale regional survey during a pandemic. Among the design challenges was selecting the right combination of local languages to interview respondents for a representative sample of each country’s population. We settled on a total of 18 languages, including English, in the eight countries.

Each country in South Asia has unique issues around language. India, for example, has 23 official languages spoken in different parts of the country but our analysis showed we could obtain representative results by offering the survey in 11 languages. In neighboring Nepal, 19 languages are spoken but Nepali is understood by virtually everyone, making it possible to interview all respondents in Nepali. In Bhutan, the pilot survey started by using just Dzongkha until we discovered that excluded some women from responding and we added Lhotsham as another language option.

The rich diversity of South Asia means that only a few languages cross national boundaries within the region. Bengali is spoken in Bangladesh and India. Urdu is used in Pakistan and India. Tamil in used in Sri Lanka and India.

Lining up experienced translators has been another challenge. Translators must have the skill to adapt questions into colloquial language for an effective telephone survey. As Lucy Wanyee, Operations Manager at GeoPoll said, “the vernacular is different from literary or official language: it’s the way people really talk with each other, like how families talk at home.” Caroline Louisa MK, who manages the survey in India said, “India is a multi-language, multicultural country and local dialects change every 100 kilometers or so. This requires an experienced team of translators who are able to review translated documents to check the translations as well as dialects.”

Given the importance of properly translated questionnaires, we had two translators review each version of the survey before telephone interviews began. After finalizing a survey script in each language, teams of interviewers practiced reading aloud the translated questionnaires to prepare for live phone calls.

As part of the quality control process during the pilot, we listened to interviews in all 18 survey languages and gave tips and feedback to interviewers to help them obtain valid responses.

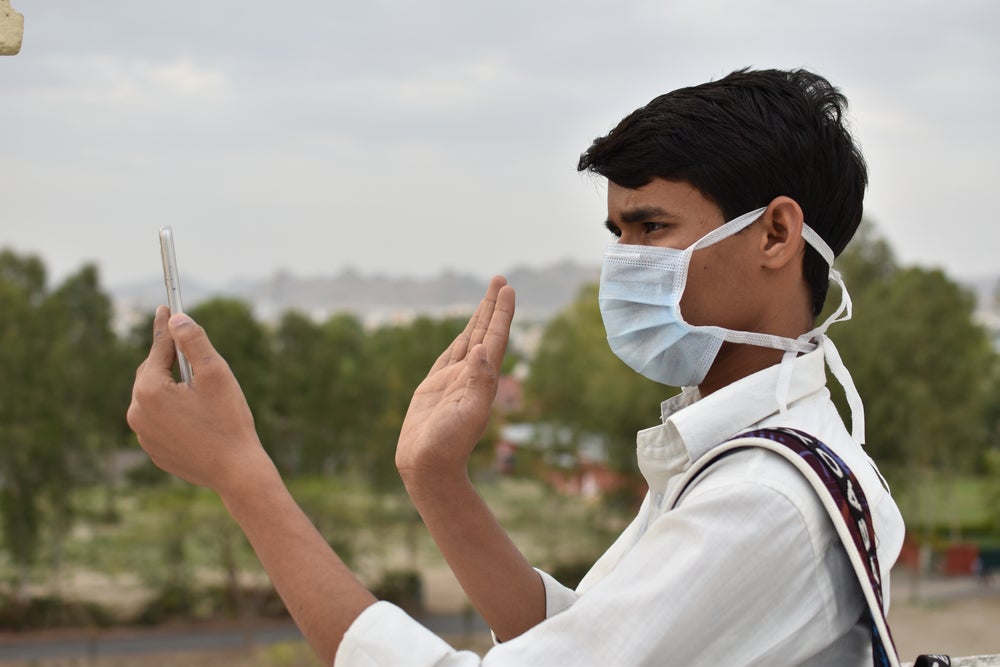

Mobile phones replace face-to-face interviews

Another big challenge is administering the survey during a pandemic. Ideally, face-to-face interviews would be conducted because of the detailed nature of the questions. But the social distancing protection needed by respondents and by our survey teams made mobile phones the next-best choice. Survey enumerators use random digit dialing and the questionnaire is designed to take no longer than 15 minutes.

It was a new experience for most of our teams to prepare a phone survey. An Afghanistan survey manager said he had used phone surveys only with a small, targeted population, such as refugees returning home—not with the general population.

“Most people in urban areas in Afghanistan are educated, and they easily understand the survey questions, compared to respondents in rural areas of Afghanistan. It’s a bit challenging to make them understand some of the questions, especially female respondents who are living in villages,” said a survey interviewer. “Most females in urban areas are willing to participate and talk to us independently, but in rural areas because of cultural barriers women can’t talk independently, even though all our staff is female.” Similarly, respondents in urban areas are usually familiar with the World Bank and what COVID-19 is. “But for rural areas, we have to give much more details regarding the survey and the World Bank,” she said.

How likely were people to participate in phone surveys during a pandemic?

Cooperation rates were another concern as we designed the survey. Would people be eager to talk to a stranger because of restricted social lives? Or would they hang up quickly to avoid any additional stress in their life? The pilot showed that generally, when a person answered their phone and agreed to participate, they answered all survey questions because of high interest in COVID-19. The pilot’s conversion rate—the share of completed calls out of phone calls that were answered—ranged from 39% in Bangladesh to 71% in Pakistan.

In Bhutan, supervisor Tshering Dorji, said some pilot respondents indicated they felt it was their civic duty to participate in a research survey about the pandemic. Others said they were happy to answer the survey questions as a way to contribute to COVID-19 relief efforts.

The pilot also showed that respondents were more likely to trust a woman interviewer and agree to take the phone survey. In Maldives, supervisor Mahdhy Shahid said that female enumerators were even more successful in convincing people to participate in the survey than him, though he had more experience conducting social science research in the past. Trust in the enumerator is especially important for women respondents—their survey participation will help us capture the labor market changes that South Asian women are experiencing during the pandemic.

The region-wide survey will help us better understand changes in society throughout South Asia triggered by the COVID-19 outbreak. We look forward to sharing the survey results soon.

The survey is led by the World Bank’s Poverty and Equity Global Practice. The team comprises Afsana Khan, Arshia Haque, Baburam Niraula, Cheku Dorji, Chinthani Sooriyamudali, Erwin Knippenberg, Hisham Esper, Jui Shrestha, Laura Moreno, Liza Maharjan, Nandini Krishnan, Nethra Palaniswamy, Nelly Obias, Nishtha Kochhar, Ravindra Shrestha, Shiraz Hassan, and Vijayaragavan Prabakaran

The survey is supported by the Program for Asia Connectivity and Trade (PACT), a South Asia regional trust fund administered by the World Bank and funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO). Additional support from the Trust Fund for Statistical Capacity Building (TFSCB-III) administered by the World Bank funded by UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO), the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Ireland, and the Governments of Canada and Korea is also gratefully acknowledged.

Join the Conversation