The U.S. Federal Reserve System has taken new steps toward raising interest rates, but there is a disconnect between what the Fed and markets think will happen. What does it all mean for emerging and developing countries?

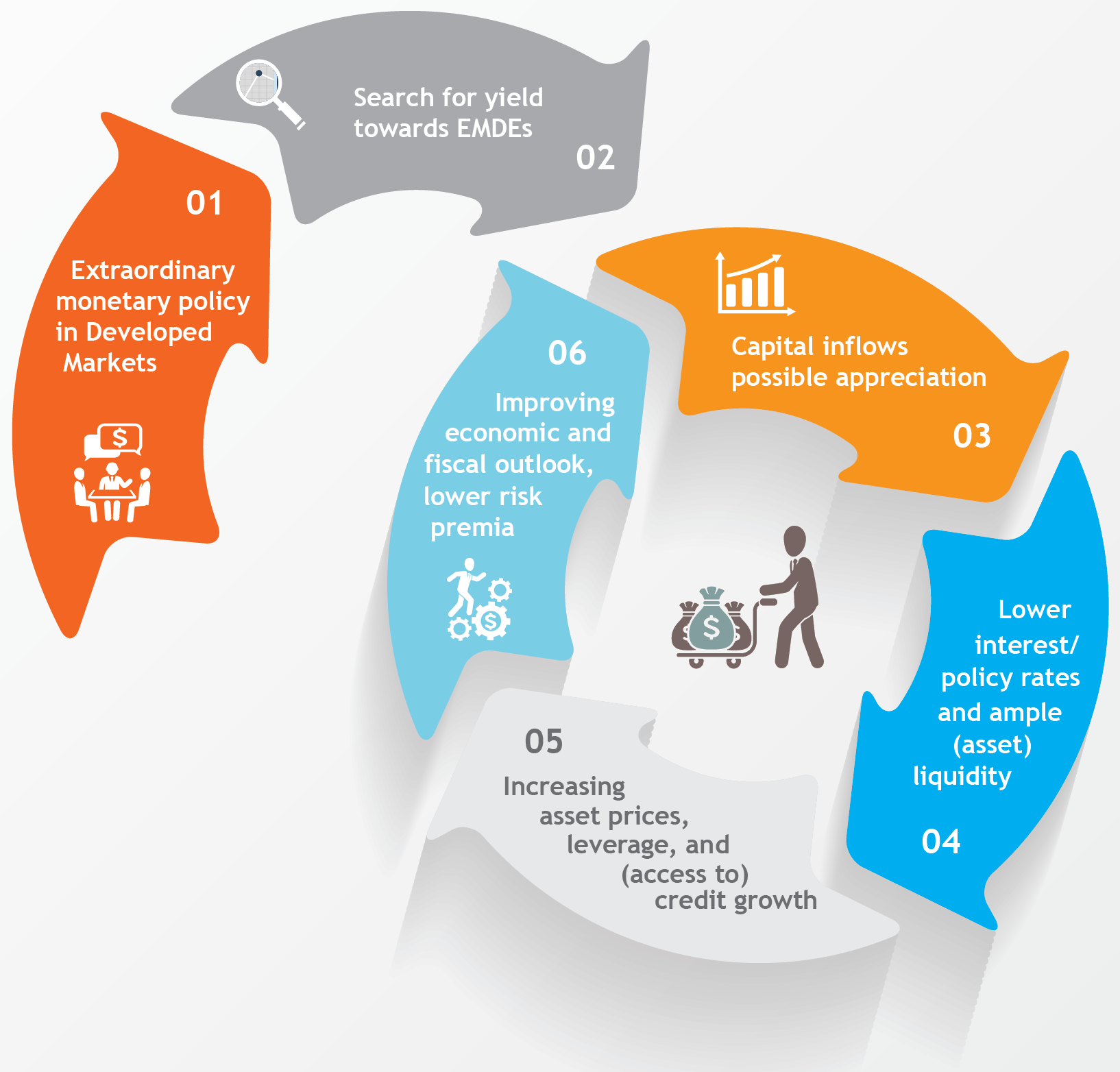

Central banks in developed economies have created an environment of ultra-low interest rates to rekindle economic growth and to battle falling inflation. They’re doing this by keeping policy rates close to zero and “printing money” on an unprecedented scale via a veritable alphabet soup of programs, such as QE, CE, LTRO and TLTRO.

These low interest rates have put a lot of pressure on investors, such as pension funds, to generate a decent return, setting off a massive search-for-yield frenzy.

This search for yield has created a cash tsunami that has also rolled on the shores of many emerging and developing economies.

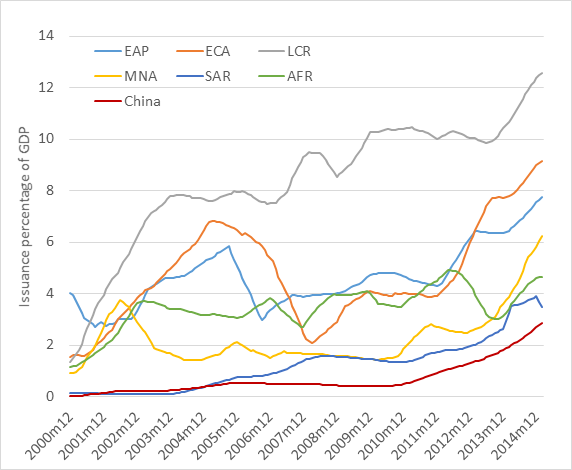

As a result, foreign investors current allocate more than $4 trillion to those economies. For example, during 2009-14, firms and governments in emerging and developing economies issued a staggering $1.5 trillion in external bonds, compared to $520 billion from 2002 to 2007. This is not driven by a singular region or country, but is a broad-based trend: This cumulative issuance of bonds accounts for 6.7 percent of GDP for the median country, boosting the stock of external bonds significantly.

Median outstanding external bonds to GDP ratio, by region

%

Significantly, a great deal of this debt is denominated in foreign currencies.

Unfortunately, not all of these countries are able to drink from the fire hose, because they lack the proper macroeconomic policy frameworks, capital-market depth and institutional setup to keep risks in check.

Cheap foreign money can be highly addictive. It produces a pleasant growth buzz at first: Currencies appreciate, stock markets boom, and both corporate and sovereigns gorge happily on cheap bonds and other sources of financing.

As a consequence, the balance sheets of firms and the government look healthier and people feel richer. Banks respond by lending more. This optimism translates into more consumption and investment.

Investors feel vindicated about the growth prospects and open the fire hose even further. The sky’s the limit.

Of course, there is a catch.

As the value of the currency appreciates, exports weaken as the country becomes less competitive, while demand for foreign products rises. The result is that the current account can weaken. Moreover, asset valuations can quickly become overly optimistic, particularly in countries with small and shallow capital markets. Banks become increasingly less picky when they provide new loans.

Meanwhile, policymakers and firms grow complacent, putting off painful reforms, while debt levels continue to grow.

The Federal Reserve has recently made new steps toward raising interest rates. This is one of the reasons the U.S. dollar has gained such strength.

Expectations of what the Fed does matter a great deal, because when countries suddenly are forced to go cold turkey, the investment climate changes dramatically, as concerns immediately grow about the economy’s debt burden and growth prospects. Debt problems are particularly acute if debts are in short maturities, are in (unhedged) foreign currencies or have floating rates.

These concerns quickly become self-fulfilling, setting the virtuous cycle in reverse.

Inflows decelerate and the currency depreciates further against a backdrop of an already strong dollar. Debts denominated in foreign currencies become heavier and more difficult to refinance. Authorities might battle depreciation by spending their foreign currency reserves. But this also means there is less foreign cash to pay off foreign debt.

As foreigners pull out, stock markets fall and bond yields rise. Firms and households feel poorer and cut back on consumption and investment.

Policymakers might raise interest rates in an attempt to lure investors back, but this chokes off new lending, which depresses the economy. Moreover, debt burdens in local currencies will also start looking worse.

Currently, there is a sizeable disconnect between what the Federal Open Market Committee thinks about the future path of interest rates and what the market thinks will happen, as expressed in futures contracts.

Federal Fund Rate Expectations: Federal Open Market Committee vs. Markets

%

This uncertainty creates room for policy miscommunication – as shown by the “Taper Tantrum” in 2013, when the Fed hinted at slowing the pace of its Quantitative Easing bond-purchasing program – and sudden shifts in market expectations.

The last thing emerging and developing economies need is a group of anxious foreign investors who start jogging, ready to run for the exit.

Useful references

Avdjiev, S., M. Chui, and H.S. Shin (2014). “Non-Financial Corporations from Emerging Market Economies and Capital Flows”, BIS Quarterly Review, December 2014.

Rajan, R. (2013).”A Step in the Dark: Unconventional Monetary Policy after the Crisis”. Bank for International Settlements, Andre Crockett Memorial Lecture, June 2014.

Rey, H. (2013). “Dilemma not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence”, Federal Reserve Jackson Hole Symposium.

Shin, H.S. (2013). “The Second Phase of Global Liquidity and Its Impact on Emerging Economies”, mimeo Princeton University.

Turner, P. (2014). “The Global Long-Term Interest Rate, Financial Risks and Policy Choices in EMEs.” BIS Working Paper 441.

Join the Conversation