One walks into a doctor’s office knowing what hurts but with little knowledge of what should be done to fix it. Identifying proper treatment requires sophisticated tests, participation of experts and, often, second opinions.

Cities, arguably, are as complicated as human bodies. Our knowledge of diagnosing cities, however, is far less advanced than in human biology and medicine. Most mayors know very clearly what they want for their cities – jobs, economic growth, high incomes and a good quality of life for the people. But it is very difficult to identify what prevents private-sector firms, the agents that create jobs and provide incomes, from growing and delivering these benefits to a city. And we have no X-ray machine to aid in the effort.

As a part of the World Bank Group's Competitive Cities project, we thought hard about ways to help cities identify the roots of their problems and design interventions to address them. We set out on a journey to put together methodologies and guidelines for cities that want to figure out what they can do to help firms thrive and create jobs. We learned from our own experience of working with cities, and from other urban practitioners. We reviewed many methodological and appraisal materials, and we trial-tested our ideas.

So what have we achieved? We certainly didn’t invent an X-ray machine, but we have developed “Growth Pathways” – a methodology and a decision-support system to help guide cities and practitioners through diagnostic exercises.

The approach follows three simple steps:

- Define the problem. Any sort of analysis is only useful if it helps answer a specific question. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. We learned it first-hand when the mayor of Nairobi interrupted our presentation on the performance of the financial-services industry and said: “I have 700,000 unemployed people on the streets. How is this going to help?” The lesson was straightforward: Make sure you are addressing a relevant question before diving deep into analysis. One way of achieving this is by visualizing the problem. To do this, we developed a benchmarking tool that we call “City Snapshot.” It helps us compare city economies quickly. Today we can use this tool to demonstrate to a mayor that, for example, his city is creating jobs at half the rate of his neighbor, and that his manufacturing sector is half as productive. This helps start a conversation that gets us on the same page with city leaders and prevents time wasted on deeper analytics on issues that are of little relevance to our clients.

- Structure the analysis. Cities are complex. There are tons of factors that can constrain private-sector growth. They range from poor quality of local roads, to land titling, to lack of talent in the area, or all of those factors together. The bottom line is that there are lots of things to consider, and the World Bank Group already has lots of techniques to analyze them. So the main problem is figuring out which technique is appropriate in a given context. Unfortunately, we have found no "silver bullet" to cut through this complexity. Instead, we’ve created a catalogue of analytical techniques that World Bank Group teams offer and we've structured them according to a relatively simple framework. The framework arranges tools along two dimensions – types of enabling conditions and types of firms. This way, we can match analytical techniques to problems and we can readily find a tool that focuses on understanding the most relevant issues — whether in the agro-processing industry (a type of firm), or the lack of technical specialists (an enabling condition), or the lack of technical specialists in the agro-processing industry (both).

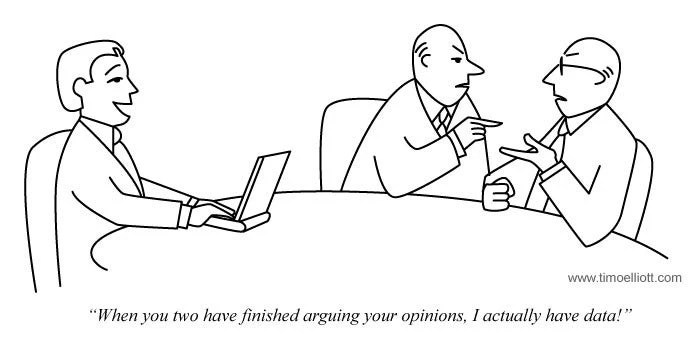

- Know how to turn numbers into actionable interventions. Turning good analysis into policies and public investments is not as straight forward as it may seem. Technocratic solutions are often not the most actionable ones. So whatever analytical techniques we propose, they're likely to take us only part of the way and to serve just as a support mechanism for decision-makers. A look at successful cities like Bucaramanga in Colombia, Gaziantep in Turkey or Coimbatore in India suggest that the best policies often emerge from a close dialogue among various actors in the public and the private sectors. Only policies devised this way can fully account for local conditions and offer local leaders a sense of ownership, and thus have a much better chance of being implemented. The role of analysis is in directing and informing the dialogue. The main challenge for analysts is to let go of the results and let the solution emerge.

The straightforward but inevitable conclusion would have to be that there is no way of knowing, with certainty, all the answers to the problems of cities, whatever methodologies or techniques we use. Doctors also can’t cure everything, but with x-rays, MRIs and blood tests they can do quite a lot. Putting our efforts together to improve analytical tools for city competitiveness will set us on the right way to making city economies healthier.

* “Growth Pathways – A Diagnostic Methodology for City Competitiveness“ will be launched as one of the background papers to the “Competitive Cities for Jobs and Growth” report in December 2015.

** "Competitive Cities for Jobs and Growth” has been made possible through support from the Competitive Industries and Innovation Program (CIIP). The overview report and companion papers will be launched in Washington, D.C. in December 2015 – with a number of regional events throughout this year.

Join the Conversation