So does trade reduce poverty? In a recent World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, my colleague Maëlan Le Goff and I examine this question, looking at the connection between poverty and trade liberalization in 30 African countries between 1981 and 2000. Our results suggest that trade does tend to reduce poverty, but only in specific settings: in countries where financial sectors are deep, education levels high, and governance strong.

This result corresponds to a certain logic. These three dimensions (finance, education, and governance) capture an economy’s ability to reallocate resources – to move them away from the less productive sectors to the more productive ones. This, in turn, allows countries to better take advantage of the opportunities offered by trade.

A more developed financial sector allows banks and investors to more quickly identify new and promising sectors and redirect credit to them. A more educated population is more able to acquire the new skills sought by growing sectors and adjust more rapidly to the changing conditions of the labor market. Finally, better governance allows contracts to be made and conflicts to be resolved more easily.

It’s easy to imagine how any of these factors could help pull people out of poverty. An easy-to-get business loan could help a new grocery store open and create new jobs, for example. A literate worker would be more able to transition from low-paying agricultural work to a job in a new factory. And foreign investors, observing that a country’s government enforces contracts, might be more willing to invest in a new plant, hiring local workers. If these conditions are not met, however, greater openness to trade could be associated with higher levels of poverty.

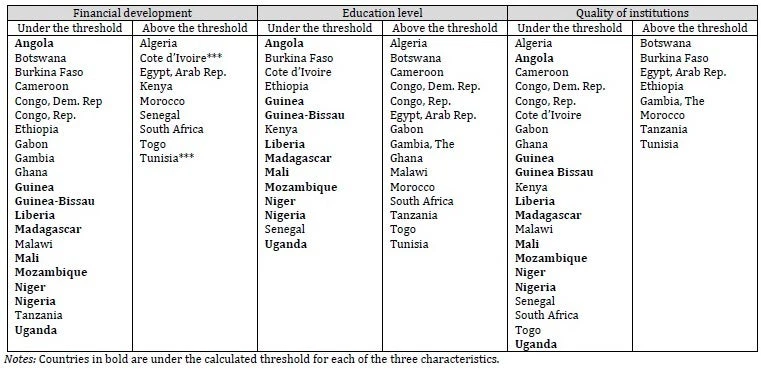

The good news is that our results suggest that many African countries meet these conditions and are well positioned to take advantage of the opportunities offered by trade. On average in Africa, however, while the financial sector (measured by the ratio of private credit to GDP) is deep enough and the level of education (measured by the share of the population over age 15 with completed primary education) is high enough to benefit from trade, institutions are generally too weak. A few countries, such as Liberia or Mali, do not meet any of the three conditions.

Countries above and below the thresholds (1981-2010)

Source: Le Goff, Maëlan and Raju Jan Singh, "Does Trade Reduce Poverty? A view from Africa."

These countries will need to enact a wide range of policies designed to harness the power of trade for economic development. Inadequate policies and institutions, weak human capital, and limited financial development are not only bad for a country’s welfare. They also hold back the poor, denying low-income residents of developing countries the benefits of freer trade.

These results are consistent with the recent literature arguing that the benefits of trade are not automatic, but rather depend on good policies, too. Our findings suggest that these policies should encourage the financing of new investment, the effective resolution of conflicts, and the ability to adjust and learn new skills. This accompanying policy agenda should allow resources to be reallocated away from less productive activities to more promising ones. Trade liberalization should therefore not be seen in isolation.

Join the Conversation