The six land corridors that are the “Belt” part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) connect more than sixty countries, a number that keeps growing as more and more countries join. However, even as the initiative progresses, there are still open questions as to what each participating country will gain from the initiative.

How can a country best benefit from the BRI? How should projects be prioritized and sequenced? What opportunities emerge as a result of participating? A new World Bank research paper explores these recurring questions.

Our analysis is based on exploring the position of each country’s economic centers along the BRI network of corridors. Ultimately, an initiative such as the BRI will change the way economic centers are connected. Productivity, competition, market opportunities, and transport and logistics costs could all be impacted.

Participating countries and cities within them will all certainly be affected by the implementation of the BRI. However, the extent of the impact will depend on where along the corridors a country or city is located relative to other economic centers. The difference matters, and is comparable to a storefront being located in a cul-de-sac or a thoroughfare. Countries and cities on the “thoroughfare” may see more opportunities to add value and intermediate trade, whereas countries in the “cul-de-sac” serve as an end node only.

In our research, we have identified four ways that geography and connectivity could impact BRI countries.

How can a country best benefit from the BRI? How should projects be prioritized and sequenced? What opportunities emerge as a result of participating? A new World Bank research paper explores these recurring questions.

Our analysis is based on exploring the position of each country’s economic centers along the BRI network of corridors. Ultimately, an initiative such as the BRI will change the way economic centers are connected. Productivity, competition, market opportunities, and transport and logistics costs could all be impacted.

Participating countries and cities within them will all certainly be affected by the implementation of the BRI. However, the extent of the impact will depend on where along the corridors a country or city is located relative to other economic centers. The difference matters, and is comparable to a storefront being located in a cul-de-sac or a thoroughfare. Countries and cities on the “thoroughfare” may see more opportunities to add value and intermediate trade, whereas countries in the “cul-de-sac” serve as an end node only.

In our research, we have identified four ways that geography and connectivity could impact BRI countries.

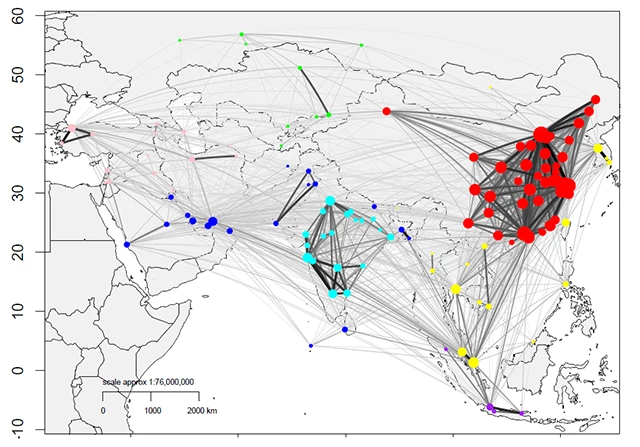

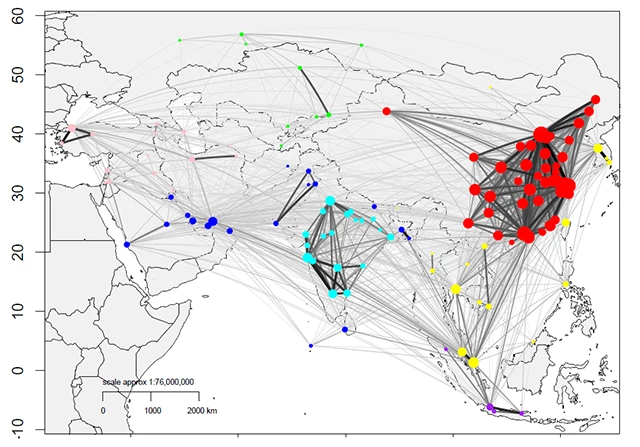

- The BRI corridors primarily enhance the connectivity between China and existing economic communities. Over the past three decades the world economy has evolved into distinct economic communities – of which the European Union and ASEAN are the most prominent examples. To a large extent, China is not party to some of these important “walled gardens.” Through our analysis, we identify five communities that the BRI corridors will bridge between: a ‘Chinese community’ and a ‘Southeast Asian community’ centered on Bangkok and Singapore; a ‘Central and West Asian community’; a ‘South Asian’ community; or a ‘North Asian’ community. As intra-regional connectivity in each of the regions is already high, the BRI corridors essentially are bridges between China and these other communities.

- The development of BRI corridors should prioritize existing gaps or weak links in infrastructure networks. BRI investment should be prioritized in areas where road, rail, and information networks are the weakest. These investments should be coupled with the negotiation of new trade and other agreements, and the improvement of the regulatory and policy frameworks for the provision of services. In the paper we identify some of the links that could be prioritized for development, especially along the China – Central Asia – West Asia Economic Corridor and the Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar Economic Corridor.

- Developing the BRI corridors should be accompanied with new cooperation agreements. Borders, and countries’ abilities to cooperate across them, impact connectivity. The thickness of borders can be reduced by negotiating new agreements among the countries along a particular corridor. Negotiating new trade agreements is an indispensable part of BRI, in some instances much more important than building new physical infrastructure.

- Different cities and towns should plan to leverage their positions to maximize the benefits of BRI. In China, we identify seven cities (Baotou, Zhengzhou, Xian, Lanzhou, Urumqi, Kunming and Qujing) that will become more central and important within the BRI networks and be critical to how China engages with the BRI countries. In addition, we identify cities in other participating countries and along each corridor that are also well placed to benefit significantly from improvements to the trade routes. The centers are Novosibirsk, Irkutsk Yekaterinburg, and Krasnodar (Russia), Almaty, and Astana (Kazakhstan), Tehran (Iran), Istanbul (Turkey), Kabul (Afghanistan), Yangon (Myanmar), Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), Bangkok (Thailand), Hanoi (Vietnam), Singapore (Singapore), Rawalpindi, Bahawalpur, Islamabad and Karachi (Pakistan), Dhaka (Bangladesh), and Kolkata (India). These centers are well placed to generate, add value to or play roles as fulcrum for BRI corridor flows. The corollary is that all other centers have to take special measures to enhance their roles in the emerging corridors and to benefit from them. The centers cannot be complacent as otherwise they will not see much impact from BRI.

Join the Conversation