The COVID-19 pandemic has reshaped our cities in many ways. While the number of motor vehicles on the road has plummeted during lockdown, an increasing number of people have turned to walking and biking, moving speedily and safely through once congested streets. The shift has brought some visible changes: local air pollution has dropped by up to 60% globally, and cities that used to be covered with a thick blanket of smog are experiencing their first blue skies in a long time.

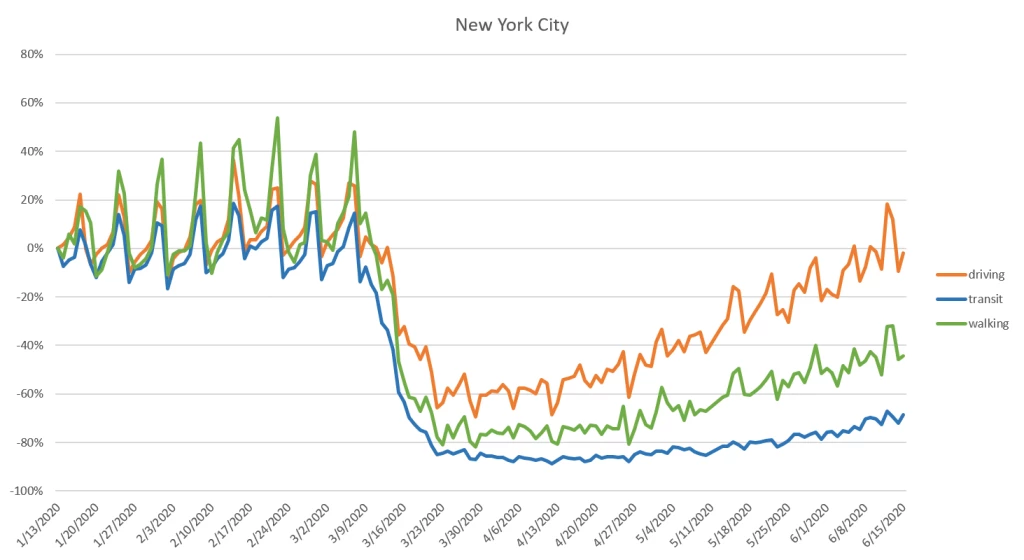

But what will happen now that cities are gradually getting out of lockdown? At the moment, many urban residents feel that public transport puts them at a higher risk of being infected, and perceive private vehicles to be safer. As a result, car use has recovered much faster than mass transit so far—morning traffic in major Chinese cities is now even higher than 2019 averages. That means higher levels of air pollution, more congestion, and a lower quality of life.

But there is an alternative to rampant motorization. If the current public health crisis makes individual modes inherently more appealing to users, why not use this as an opportunity to promote cycling and walking, which would produce greater social benefits, reduce pollution, and improve urban livability?

We are seeing encouraging signs in some cities, where traffic on urban cycling networks is surging. For example, in Buenos Aires city bike use increased 129% before total lockdown and a similar increase was observed on China’s bikeshare systems.

Yet in many parts of the world, the conditions for cyclists and pedestrians remain extremely challenging. In India, only 10% of urban streets have sidewalks, resulting in high fatality rates for non-motorized transport (NMT) users. In Africa, pedestrians and cyclists account for 44% of road traffic fatalities. The situation is simply not acceptable—no one should have to feel like they are gambling with their life every time they decide to walk down the street or hop on a bike.

So, why is non-motorized transport lagging so far behind? After all, cities around the world have laid out plans and manuals to encourage cycling and upgrade walking infrastructure, often in an effort to improve air quality. The required facilities are relatively inexpensive to build, and there is no shortage of guidelines on how to best design safer streets for walking and biking. It seems like the problem is less about capacity and more about opportunity: due to many competing agendas of city governments, the car has largely dominated the fierce competition for urban space. This is one of the main reasons why NMT plans rarely move from design to implementation.

The disruption created by COVID-19, however, has significantly changed people’s perception of walking and biking, leading many decisionmakers to rethink the role of active transport. In fact, several major cities have already seized that momentum to advance their urban sustainability agenda. From Lima and Bogotá in Latin America, to Berlin and Milan in Europe as well as Kisumu in Kenya or Auckland in Oceania, more than 1,800 cities have taken action to bolster NMT since the start of the pandemic. India put in place a nationwide program known as the Cycles4Change Challenge. Some of the concrete NMT measures that have been adopted in response to COVID-19 include:

- Closing certain streets to motorized vehicles. In Oakland, the city closed nearly 10% of its streets.

- Expanding NMT space or creating new priority zones for cyclists and pedestrians, such as Vienna’s “shared spaces” (“Begegnungszonen”).

- Creating temporary or “pop-up” bike lanes through low-cost interventions (signage, traffic cones, concrete barriers), as seen in Lima or Berlin

- Providing equipment and finance e.g. bike provision, bike commuter benefits, shower facilities at workplaces. In India, for instance, the Cycles4Change Challenge is helping cities build capacity to launch bikeshare systems or create pop-up bike lanes.

Through the lockdown, city dwellers have experienced urban space free from noisy traffic for the first time since the rise of the automobile. Many have rediscovered walking and biking, filling city streets with people rather than cars. Amid all the chaos, the pandemic has given us a glimpse into what a pedestrian-friendly, bike-friendly city could look like, with fewer road fatalities, less pollution, and a better urban environment.

This cannot be just a passing fad: now that the pandemic has opened our eyes to the importance of non-motorized transport, we have a small window of opportunity to transform short-term responses into long-term change—and to create livable, breathable cities for all.

Want to learn more? Make sure to watch our recent webinar on “COVID19 - A chance for Non-Motorized Transport in Cities,” hosted by the World Bank’s Urban Mobility Global Solutions Group.

With contributions from Nupur Gupta, Gerald Ollivier and Pranjali Deshpande.

Join the Conversation