woman doing research while holding equipment. | © National Cancer Institute / Unsplash

woman doing research while holding equipment. | © National Cancer Institute / Unsplash

When many of us were growing up, the idea of buttonless phones, video calls, self-driving cars, and virtual assistants like "Siri" only existed in futuristic movies. Jobs like “video blogger” or "social media manager" were unheard of 20 years ago. The advancement of technology has significantly altered the way firms operate and individuals interact in just a few years. The pace at which technology is reshaping economies and societies is unprecedented––technological progress will be the most critical factor in defining productivity and economic growth. How technology and institutions merge will determine how the benefits of technology are distributed among countries, regions, and individuals.

Over the past 40 years, technological advancements in European countries have primarily benefited college graduates and a small group of large, innovative "superstar" companies, leading to increased distributional tensions. In response, a recent World Bank report aims to answer two crucial questions:

- How can we encourage small businesses to adopt technology so that monopolies are prevented?

- Which reforms are necessary to ensure education systems equip students and ongoing learners with the skills needed to succeed in a constantly changing job market dominated by technological advancements?

University graduates will be more in demand than ever. | © Dom Fou / Unsplash |

Differences in technology adoption rates among small and large firms contribute to distributional tensions. Combining firm surveys covering 32 European countries between 2014 and 2022, the report shows that larger, more productive firms are more likely to adopt new technologies. Small firms in the EU are slow to adopt new technologies—relative to small firms in the US—since they lack sufficient access to finance, operate in a context of low levels of human capital, and tend to have low managerial capacity.

Technology gives larger firms a competitive edge. | © Christian Wiediger / Unsplash |

Companies that adopt new technology increase the number of non-routine cognitive tasks performed while decreasing routine manual tasks. Once adopted, technology increases productivity, and total sales. But it also increases the demand for university graduates, exacerbating the wage differentials between highly educated workers and the rest.

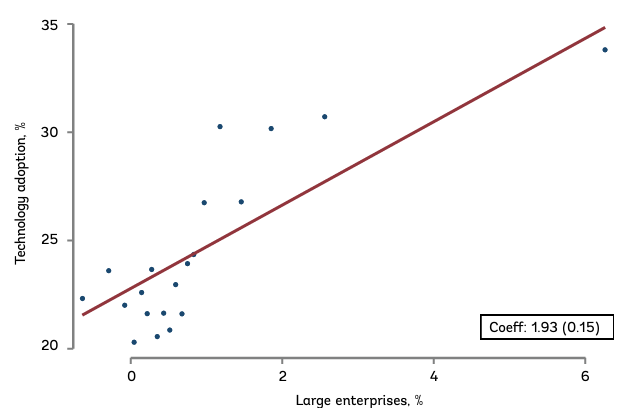

Larger and more productive Italian firms are more likely to adopt new technology, which, in turn, allows them to become larger, creating a positive relationship between technology and market concentration. As shown below, countries and sectors with higher levels of technology adoption tend to have a larger market share accounted for by large enterprises. This positive relationship between technology adoption and market concentration results in a decrease in the share of total income going to labor.

Figure 1: Sectoral concentration and technology adoption.

Source: Authors’ estimations using EU data

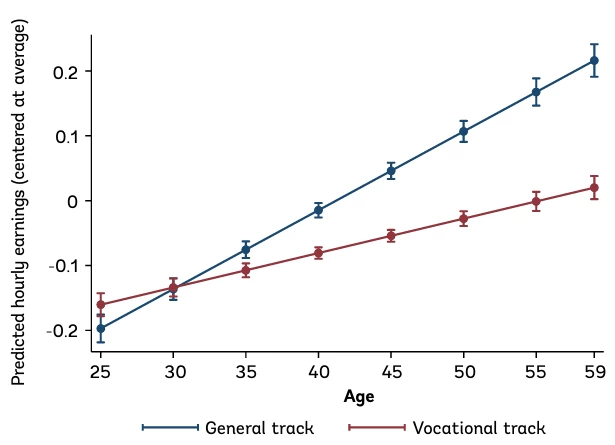

The report highlights that vocational education graduates lack the necessary skills to adapt to technological advancements. This is a crucial finding for the EU, where vocational training is common, and most students enrolled in such programs come from low-income backgrounds. According to our findings, graduates with vocational education and training (VET) are initially more likely to find employment than their peers with a general secondary education degree. However, this advantage fades within five to seven years of entering the workforce. Additionally, the report shows that VET graduates have lower earning potential than non-VET graduates (see graph below). This is partly due to the poor match between the skills VET graduates possess and the skills demanded by new technologies, which require strong foundational skills: numeracy, literacy, and socio-emotional skills.

Figure 2: Age profile for earnings of VET and general secondary graduates

Source: Authors’ estimations using PIAAC data.

What can policy makers do?

Second, countries have the potential to use technology better to fulfill the needs of society. In the EU, some tax policies result in unintentional capital subsidies, leading to increased automation and labor-substituting technologies. Modifying tax incentives can encourage technological investment, complement labor, and create high-quality jobs. Moreover, EU institutions must invest in research and innovation to promote the spread of technological advancements that integrate low-skilled workers into production processes.

Third, European education systems must ensure all graduates possess a minimum set of core foundational skills. Due to rapid technological advancements, tasks performed in firms are constantly evolving , causing job-specific professional competencies to become outdated quickly. In this scenario, foundational skills have become more critical than ever for workers to reinvent themselves into new occupations.

As we move toward the future, it is important to remember that we have the power to shape it. The evidence and data we have allow us to identify and address the challenges that come with technological progress. By building institutions that promote equality and productivity, we can create a future where everyone benefits from technology, especially those who need it most . We can make this vision a reality with leadership, resources, and a firm commitment.

Join the Conversation