Poverty is widespread in Somalia, but identifying the location and needs of poor people is increasingly difficult due to the country’s ongoing conflict and violence. Even less is known about how gender affects poverty among internally displaced populations (IDPs). Using an innovative survey that collected information using new technologies, the Gender Dimensions of Forced Displacement Research Program set out to find out more.

Using satellite images and smart algorithms to identify populations for sampling, the Somalia High Frequency Survey (HFS) closes that critical data gap while overcoming obstacles of accessing insecure areas. Importantly, the HFS identifies Somalis that have been internally displaced.

UNHCR estimates that there were three million IDPs (about 17% of the population) at the end of 2020, uprooted by different phases and types of armed or clan conflict, drought, famine, and natural disasters. Prolonged conflict has increased the proportion of female-headed households, with nearly half of all households reporting a female head for over a decade.

At first sight, gender seemed to have little impact on poverty risk. Although poverty rates are higher among IDPs than non-IDPs (77% versus 66%), male-headed households are poorer than female-headed ones among both groups. Further analysis reveals a more nuanced picture. Once household and individual characteristics are considered, IDP families with children, especially single female

caregivers, experience the highest poverty rates. Compared to IDP families without children, IDP single female caregivers and couples with children are 17-20 percentage points more likely to be poor, which this is not the case among non-IDP families. Families are disrupted during displacement; some children and the elderly join other households, while other members remain behind. We find that such changes increase poverty risk, even in situations where poverty is already widespread.

What then protects families from poverty?

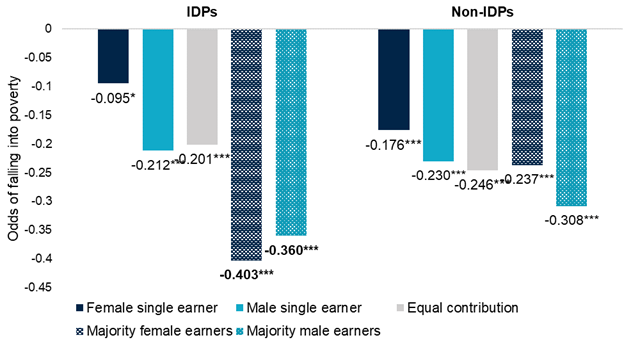

For IDP households, the least poverty risk is associated with having more female earners, while more male earners is associated with the least poverty risk—about 40% less—for non-IDP households. As the chart below shows, having more income earners reduces poverty risk for all households, but IDPs benefit most. This may be because some of the normative constraints to women’s employment outside the household are lifted during displacement.

IDP households with several female earners have more adults and fewer children than those with a male or female single earner, or those that rely on remittances. However, with an average of two children and four adults, they are very similar to households with multiple male earners. Apart from the household head and spouse, additional female earners are in most cases adult children. Few of them are sisters or nieces of the household head or spouse. And they do not belong to polygamous households.

IDP households benefit most from having more earners

What can be learned from our research methods?

Our findings show that it is important to go beyond headship to understand gender differences in the poverty risk and formulate policies. Of particular relevance is women’s lack of access to economic opportunities and their caring responsibilities. Had we simply stopped at female headship, we would have concluded women are better off than men in Somalia.

What can be done?

Poverty reduction policies and programs in Somalia are important for all households but targeting and delivery methods are still relevant . Besides factors like geographic location and nutritional status, cash transfer programs need to consider household composition. Baxnaano, the first government cash transfer in Somalia is already doing this by focusing on women with children under five. Delivering cash transfers through mobile money—as it is the case of Baxnaano— can be important for women where insecurity and gender-based violence risk limit their mobility. Baxnaano was able to scale up to respond to the ‘triple shock’ of the desert locust infestation, COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic, and floods, reaching close to 100,000 households with emergency cash transfers for livelihood protection.

The design of work programs to promote economic opportunities must consider whether specific activities are needed to increase women’s earnings and productivity. For example, public works programs with a heavy manual labor component often put women at a disadvantage. This constraint can be alleviated by including activities that are suitable for both men and women. Regardless of the activity, it is important to ensure equal wages between women and men. Care responsibilities are another important consideration. Public work and livelihood programs can embed support services such as community-childcare facilities, flexible hours, and transport assistance or locating work assignments for women close to their homes.

The Gender Dimensions of Forced Displacement is led by Lucia Hanmer and Diana Arango, under the direction of Hana Brixi, Global Director, Gender. It is part of the program "Building the Evidence on Forced Displacement: A Multi-Stakeholder Partnership.”The program is funded by UK aid from the United Kingdom's Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO). It is managed by the World Bank Group (WBG) and was established in partnership with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

This blog is part of a blog series curated by the World Bank’s Somalia Women’s Empowerment Platform that highlight evidence and solutions on women’s and girls’ empowerment in Somalia.

Join the Conversation