Number of refugees by years in exile

Number of refugees by years in exile

"The average length of time that refugees spend in camps is 17 years." This cruel statistic has been quoted many times, influencing our perception of refugee crises as never-ending events which are spinning out of control. It has significant implications when deciding the type of aid that is needed, the combination of humanitarian and development support, and the possible responses to the crisis.

But is it true? Not so.

In fact, the "17 year" statistic comes from a 2004 internal UNHCR report, and it was accompanied by many caveats which have been lost along the way. The statistic does not refer to camps since the overwhelming majority of refugees live outside camps. It is limited to situations of five years or more, so it is an average duration of the longest situations, not of all situations. Most importantly, it refers to the duration of situations, not to the time people have stayed in exile.

Take the situation of Somali refugees in Kenya. Refugees started to arrive massively around 1993, about 26 years ago. Their number now stands at 252,500. But can we say that all 252,500 have been in exile for 26 years?

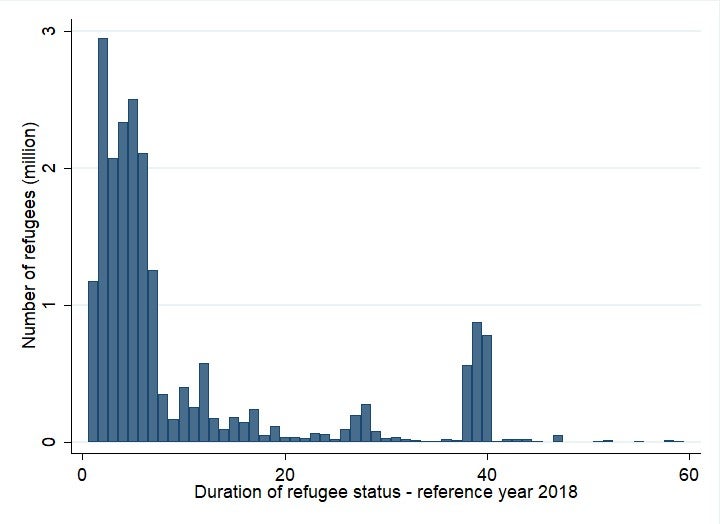

In fact, forced displacement situations are inherently dynamic: numbers vary every year, reflecting political and military developments in the country of origin (figure 1). In fact, a large part of the current refugees did not arrive before 2008, i.e. about 10 years ago.

Along these lines, and using data published by UNHCR as of end-2018, we re-calculated the earliest date at which various cohorts of refugees would have arrived in each situation (see our methodology as we developed it for this earlier working paper). We then aggregated all situations into a single "global refugee population" and calculated global averages and median durations.

So what are the results?

When we look at the "global refugee population" (see Figure 2), we can now distinguish several distinct episodes of displacement:

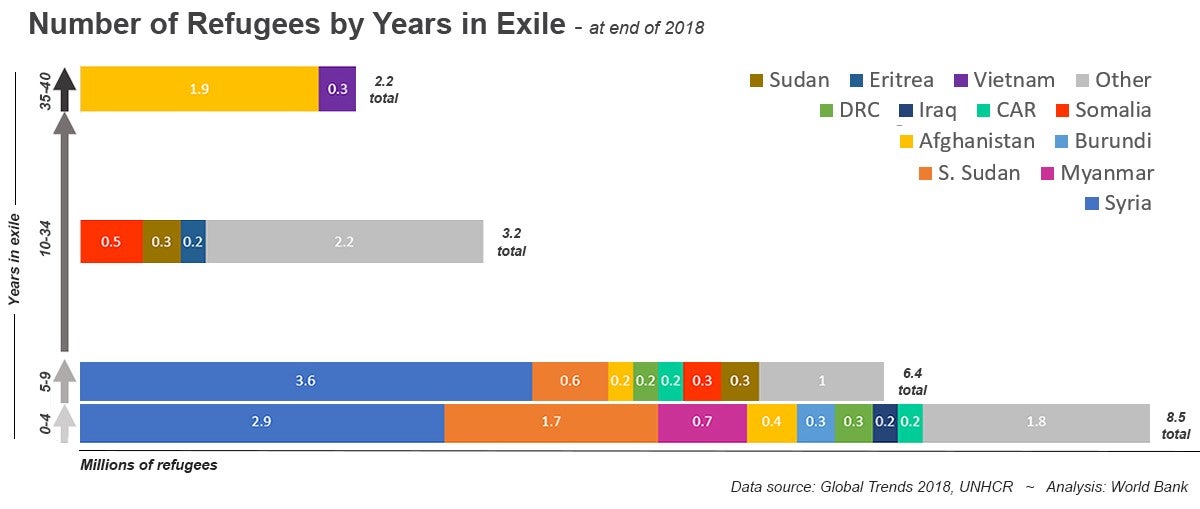

Now let’s group these figures by largest waves of arrivals (Figure 3):

There is a large cohort of about 8.5 million "recent refugees," who arrived over the last four years. This includes about 2.9 million Syrians, as well as people fleeing from South Sudan (1.7 million), Myanmar (0.7 million), Afghanistan (0.4 million), Burundi (0.3 million), the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (0.3 million), Iraq (.2 million), and the Central African Republic (0.2 million).

Another large cohort, of about 6.4 million, has spent between 5 and 9 years in exile. It includes refugees from Syria (3.6 million), South Sudan (0.6 million), the bulk of the current Somali refugees (0.3 million), and people fleeing from Sudan (0.3 million), the Central African Republic (0.2 million), Afghanistan (0.2 million), and the Democratic Republic of Congo (0.2 million).

About 3.2 million people have been in exile between 10 and 34 years. This includes years during which numbers are relatively low, and two episodes where they are higher, around 17 years ago, with the arrival of about 0.3 million Sudanese refugees, and around 27 years ago, with the arrival of about 0.5 million Somalis and 0.2 million Eritreans.

Lastly, a large group of refugees has been in exile for 35 to 40 years: these 2.2 million refugees include mainly Afghans (1.9 million), but also about 0.3 million Vietnamese who fled their country during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Finally, there are few very protracted situations, up to 58 years, including mainly Western Sahara.

We can now turn to average durations. As of end-2018, the median duration of exile stands at 5 years, i.e. half of the refugees worldwide have spent 5 years or less in exile. The median has fluctuated widely since the end of the Cold War, in 1991, between 4 and 14 years. By contrast, the mean duration stands at 10.3 years, and has been relatively stable since the late 1990s, between 10 and 15 years.

But this leads to another important finding: trends can be counter-intuitive. In fact, a decline in the average duration of exile is typically not an improvement, but rather the consequence of a degradation of the global situation . The averages increase in years when there are relatively few new refugees, and they drop when large numbers of people flow in, for example in 1993-1994 (with conflicts in Former Yugoslavia and Rwanda), in 1997-1999 (with conflicts in DRC and other parts of Africa), after 2003 (with conflict in Iraq, Somalia, and Sudan), and since 2013 (with the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic).

We also looked at the number of people who have spent more than five years in exile. As of end-2018, this number stands at 11.9 million. The number of protracted refugees had been remarkably stable since 1991 at 5 to 7 million throughout most of the period, before dramatically jumping in the last 3 years. For this group, the average duration of exile increases over time – largely because of the unresolved situation of Afghan refugees which pushes averages up. It is now well over 20 years.

This short analysis of UNHCR data shows that available refugee data can be used to clarify some important parts of the policy debate. It is important to ensure that this debate is informed by evidence , which can help provide a more nuanced perspective of a complex issue.

Join the Conversation