Children attend the first day of school in a refugees camp. | © shutterstock.com

Children attend the first day of school in a refugees camp. | © shutterstock.com

In this blog, we explore the intersection of data and policy, summarizing results from a novel data harmonization exercise that allows us to compare information on forcibly displaced persons (FDPs) and their host populations. The goal is to inform policy solutions that may work for both.

Data Harmonization

Although the majority of people affected by forced displacement are in low- and middle-income countries, most available evidence stems from high-income settings, underscoring the need for more inclusive data collection.

Building on earlier work to collect representative data for FDPs and hosts, we recently completed a new multi-country data harmonization effort. The datasets included stem from representative surveys covering several displacement events in the period 2015 to 2020: the influx of Venezuelan migrants in Latin America’s Andean states; the Syrian crisis in the Mashreq; the Rohingya displacement in Bangladesh; and forced displacement in Sub-Saharan Africa. The indicators in the database provide a first comparative profile of FDPs and hosts across displacement settings.

The data harmonization builds on important seed investments, while recognizing that an adequate evidence base on forced displacement remains an aspirational goal. Three policy briefs distill key findings from our initial analyses comparing refugees and hosts.

Initial analysis of the dataset shows that displaced people are faring worse than hosts, but in ways that can be addressed by informed policy.

Displaced People Face Stark Disadvantages

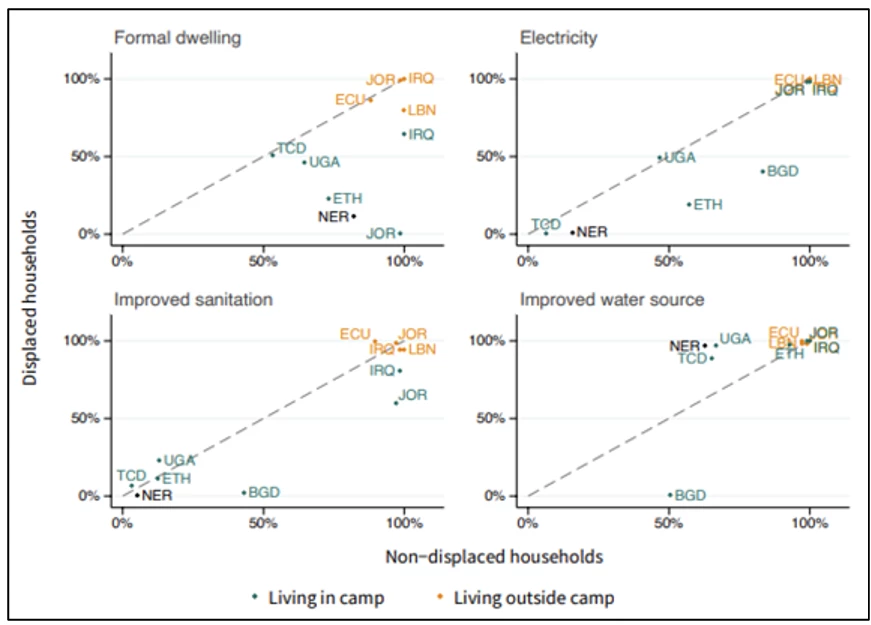

Displaced households typically experience greater deprivation compared to their local counterparts, including ownership of household and productive assets, children's educational outcomes, and labor market outcomes. We contrast the living conditions of refugees and host households in four areas: formal housing; access to electricity in dwellings; improved sanitation facilities; and improved water sources (piped, bottled, tanker trucks, or community tanks.

The graphic below shows that, for most countries, hosts have higher levels of access than refugees (most points lie below the 45-degree line). This disparity is even more pronounced in lower-income countries and among refugees living in camps.

Graphic: Housing and Access to Basic Services for Refugee and Host Households Across Countries

Source: World Bank (2023). A profile of forcibly displaced populations and their hosts.

Policy Choices Can Narrow the Gaps

Data show that the policy environment has a measurable impact on how displaced people fare, reducing outcome gaps between FDPs and hosts. For example, a more liberal policy environment, allowing refugees the right to work and move freely, is associated with higher levels of refugee employment, particularly among women.

Education Supports an Inclusive Future

Education emerges as a crucial factor for the well-being of displaced populations. Refugee children are more likely to be in school and achieve better educational outcomes when educational policies are more inclusive.

We Can Measure More and Better

Much attention has been paid to measuring access to basic needs and monetary poverty for FDPs. But these measures do not fully capture people’s welfare or the capabilities that may shape their economic future. This is especially evident when legal restrictions hinder FDPs’ mobility and work options, underlining the necessity of broader indicators to assess overall well-being.

Prioritize Core Questions

Data collection (e.g., through surveys) will be most useful for policy if it foregrounds core areas of information and questions. Demography and education data provide insights into the future composition and human capital of FDPs and hosts populations.

Measuring the time since arrival helps us understand trajectories and assimilation, while assessing attitudes, particularly among host communities, informs integration policies. While collecting consumption data is valuable, it should not come at the expense of measuring employment, assets, and other markers of socioeconomic integration.

Leverage Data on Legal Frameworks

The considerable variation in refugee policy across developing countries has recently been documented in new datasets, such as the Developing World Refugee and Asylum Policy (DWRAP) database. This expansive coding of asylum and refugee policies provides an opportunity to see how policies shape the welfare of refugees in their host countries.

Develop a Sustainable Data Strategy

It is essential to have a coherent strategy for prioritizing data collection, considering its suitability for the intended purpose and its long-term viability. In settings with many FDPs, integrating them into nationally representative surveys can provide advantages.

Moving Forward

By harnessing data that includes both displaced people and host communities, solid evidence can be provided to inform policy discussion and allow countries to respond more effectively to the challenges of forced displacement. Meeting needs in both populations, with an eye to their common future, is the best way forward.

Governments and partners need to invest in data to advance positive outcomes for all people affected by displacement. Future research and analysis can leverage new tools like DWRAP and the World Bank’s harmonized database. The lessons outlined above may help researchers increase the policy impact of future data collection and analytic work.

Related Links:

Join the Conversation