Data on the sharing economy (Uber, Airbnb and so on) are scarce, but a recent study estimates that the revenue growth of these platforms has been dramatic. In the European Union (EU), the total revenue from the shared economy increased from around 1 billion euros in 2013 to 3.6 billion euros in 2015. While this estimate may equal just 0.2% of EU GDP, recent trends indicate a continued, rapid expansion.

This is important, as the sharing economy has the potential to bring efficiency gains and improve the welfare of many individuals in the region.

This can also generate important disruptions.

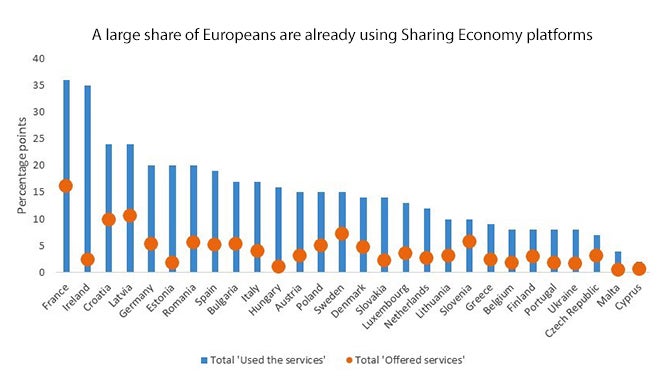

While online platforms represent a small fraction of overall incomes, the share of individuals participating in these platforms is large in many European countries. For example, roughly 1 in 3 people in France and Ireland have used a sharing economy platform, while at least 1 in 10 have in Central and Northern Europe (see figure below).

At the same time, the share of the population that has used these platforms to offer services and earn an income is also significant, reaching 10% or more in France, Latvia, and Croatia. This means that at least one out of every ten adults in these countries worked as a driver for a ride-sharing platform such as Uber, rented out a room of his or her house using a peer-to-peer rental platform such as Airbnb, or provided ICT services through an online freelancing platform such as Upwork, to name a few examples.

As mentioned above, the sharing economy can bring efficiency gains, by enabling individuals to use assets that would otherwise be idle. It can also bring environmental benefits, since assets can be shared by multiple users and thereby fewer resources are needed to make them. Moreover, the system of ratings and reviews helps lower information asymmetries by creating a mechanism to penalize bad performers and to reward good ones.

Evidence on the impact of the sharing economy on economic outcomes is still scarce. However, Cramer and Krueger (2016) find that Uber drivers spend a much larger share of the driving time and drive more miles with a passenger in the car than do taxi drivers. The authors argue that Uber is more efficient because:

- The use of Internet and smartphones allows for a much better matching of drivers and passengers than the outdated technology used by taxis

- Inefficient taxi regulations in some cities allow taxi drivers to drop off passengers outside their license area, but do not allow them to pick up another passenger there

- Uber’s flexible labor supply and prices allow for a better matching of supply and demand during high and low demand periods. Evidence for Airbnb also shows important benefits for consumers, as the platform’s additional competition helps bring down hotel rates.

In our recent report, Reaping Digital Dividends, we also look at the disruptions that the sharing economy can bring, noting that any policy recommendation would need to factor in this reality as well.

First, online freelancing – a version of the sharing economy - poses important challenges to existing labor market regulations as it is rarely governed by legal contracts. For example, in a sample mostly composed of Russians and Ukrainians, only about 12% of online freelancers had a full legal contract with their counterparts.

Moreover, many of them may not even have access to unemployment benefits, health insurance, or a pension, and will face higher risks of falling into poverty in old age or when facing negative shocks.

Second, while the sharing economy may bring economic inclusion, it can also contribute to economic disparities. In Europe, there are important gender, age, and skill gaps in the sharing economy. For example, while only about 10% of unskilled individuals have used sharing economy platforms, 27% of their skilled counterparts have done so.

Third, as is the case with international trade and general technological change, the sharing economy creates adjustment costs, especially for displaced workers who do not have the skills to find a new job or who made significant investments in their previous occupation such as taxi drivers.

Do these risks outweigh the benefits of the sharing economy? Since new technologies always find a way to breach barriers, our report argues that policies designed to facilitate the transition of displaced workers toward new jobs and to adapt labor market institutions to the new forms of work may prove to be more effective for economic development than regulatory measures to prevent inevitable changes.

Join the Conversation