Technician troubleshoots internet fiber connection_Philippines Photo by MDV Edwards/Shutterstock.com

Technician troubleshoots internet fiber connection_Philippines Photo by MDV Edwards/Shutterstock.com

Alek pays about P 1,799 ($32) a month for a 50-Mbps fiber broadband subscription in Anticala, Butuan City, in Northern Mindanao.1 His village is 28 kilometers from the city center, where residents pay just P 1,399 ($25) for the same service.

Alek is fortunate to be able to afford fiber broadband. Less than 12 percent of households in his province had Internet access, according to the 2020 census.

Access to the Internet is low and the cost high

Thirty years after it was first connected to the Internet, the Philippines still has weak broadband infrastructure. The problem is a serious one, because digitalization—a strong accelerator of inclusive growth, job creation, climate resilience, and sustainability—is not possible without good access to the Internet.

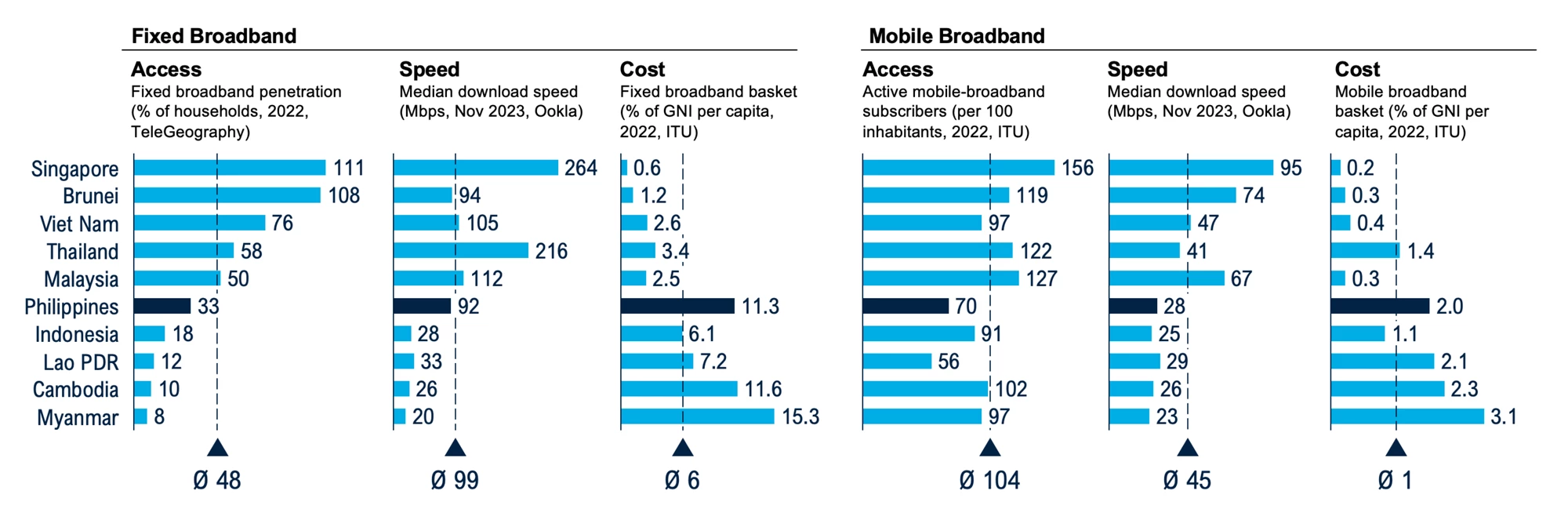

The Philippines is an outlier in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). In 2022, just 33 percent of households had access to fixed broadband, and just 70 percent of the population had an active mobile broadband subscription (Figure 1). Both figures are well below the ASEAN averages of 41 percent and 101 percent, respectively. The Philippines accounted for more than half of the ASEAN population that remains unconnected to mobile broadband.

Figure 1 Access to, speed of, and cost of fixed and mobile broadband in ASEAN countries

Broadband Internet is also more expensive in the Philippines than it is in neighboring countries. The annual charge for fixed broadband represents 11 percent of per capita gross national income (GNI)—twice as much as the ASEAN average. Mobile broadband cost 2 percent of per capita GNI—1.5 times more than the ASEAN average.

Both competition and investment are low

The Philippines’ broadband market is among the most concentrated, least invested, and most profitable in ASEAN. Two telecommunications companies account for 91 percent of mobile subscribers—a much larger share than the 70–80 percent in middle-income peers in ASEAN.

Investment in mobile infrastructure can be measured by the number of mobile towers per population. In 2022, the Philippines had 28 mobile towers per 100,000 people, according to TowerXchange (a research firm specialized in mobile towers), just a third of the average among ASEAN peers. Investment in telecommunications infrastructure as a whole declined between 2018 and 2022, with gross capital formation in telecom infrastructure down from 0.64 percent of GDP to 0.44 percent. According to data from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), more than 100 developing countries invested at least 1 percent of GDP in telecommunications in at least one year between 2006 and 2021, while the Philippines did not.

The policy environment does not help enable affordable Internet

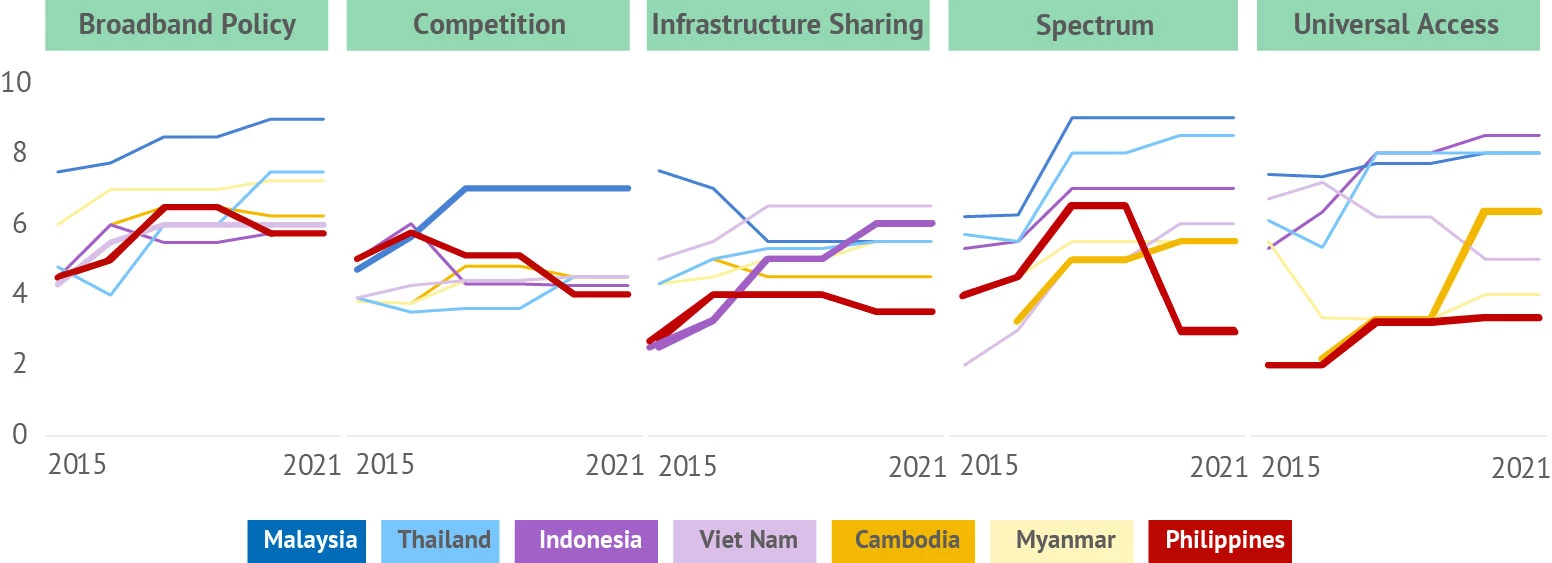

The policy environment for affordable broadband in the Philippines is among the least favorable in ASEAN. Its Affordability Driver Index (ADI) scores suggest that it has also been one of the slowest countries in the world at promoting reforms for affordable broadband.2 The Philippines’ scores declined or only marginally improved in all five of the policy areas assessed, meaning reforms on national broadband policy, competition, spectrum policy, infrastructure sharing, and universal access either stalled or were reversed (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Affordability Driver Index scores in seven ASEAN countries, by policy area

In contrast, among the 57 developing countries ADI assessed from 2017 to 2021, 40 improved their average scores. ASEAN peers that made significant progress included Cambodia (on universal access), Indonesia (on infrastructure sharing), Malaysia (on competition), and Viet Nam (on the spectrum). Globally, only four countries (Venezuela, RB, Nicaragua, Haiti, and Sudan) had scores declining and lower than the Philippines.

Reforms are urgently needed

Regulatory weaknesses are rooted in the Philippines’ legal system (specifically, the 1931 Radio Control Law and the 1995 Public Telecommunications Policy Act), which have not been updated, despite massive technological change. Upgrading its 20th century regulations is critical if Filipinos are to fully benefit from 21st century technology. Urgent reforms on broadband policy would hasten the digital transformation the Philippines needs to achieve its goal of becoming a prosperous middle-class society by 2040.

Four complementary sets of reforms could reduce barriers for competition and investment and boost access to and the quality and affordability of Internet:

- Lower barriers to entry and investment, by removing the congressional franchise requirement for broadband network deployment.

- Level the playing field, by providing diverse market participants equal opportunity to invest in broadband infrastructure.

- Enable efficient and flexible use of the radio frequency spectrum, and democratize access to the spectrum.

- Promote infrastructure sharing, by promoting co-location in passive infrastructure and mandating regulators and government agencies to coordinate infrastructure deployment.

Fortunately, a pipeline of proposed legislative actions to address some of these challenges has been prepared. Action on the them would help unlock the benefits of digital transformation.

To learn more, see Better Internet for All Filipinos: Reforms Promoting Competition and Increasing Investment for Broadband Infrastructure.

1 The story of Alek (not his real name) was taken from a public social media post by a subscriber who complained about expensive Internet in his barangay (village). The World Bank confirmed the subscription costs from Internet service providers.

2 The ADI, published by the Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI), assesses policies against a set of international best practices in five policy areas for affordable broadband, with scores ranging from 1 to 10.

Join the Conversation