Is bigger always better? Economists have long debated what size firms are more likely to drive business expansion and job creation. In industrial countries like the United States, small (young) firms contribute up to two-thirds of all net job creation and account for a predominant share of innovation. (Source: McKinsey, Restarting the US small-business growth engine, November 2012). In developing countries, evidence from Ethiopia, Ghana and Madagascar shows that the vast majority of small operators remain small, and so are unlikely to create many decent jobs over time [Source: World Bank, Youth Employment, 2014]. By contrast, ‘big’ enterprises are seen as the best providers of employment opportunities and new technologies.

The difference in role and performance of small firms in developing and industrial countries reflects to a large extent their owners’ characteristics. In the US, small firm owners are generally more educated and wealthier than the average worker, while the opposite is true in most developing countries. This point was emphasized by E. Duflo and A. Banerjee in their famous book ‘Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty’ (Penguin, 2011). Most business owners in developing countries are considered to be ‘reluctant’ entrepreneurs; essentially unskilled workers that are pushed into entrepreneurship for lack of other feasible options for employment.

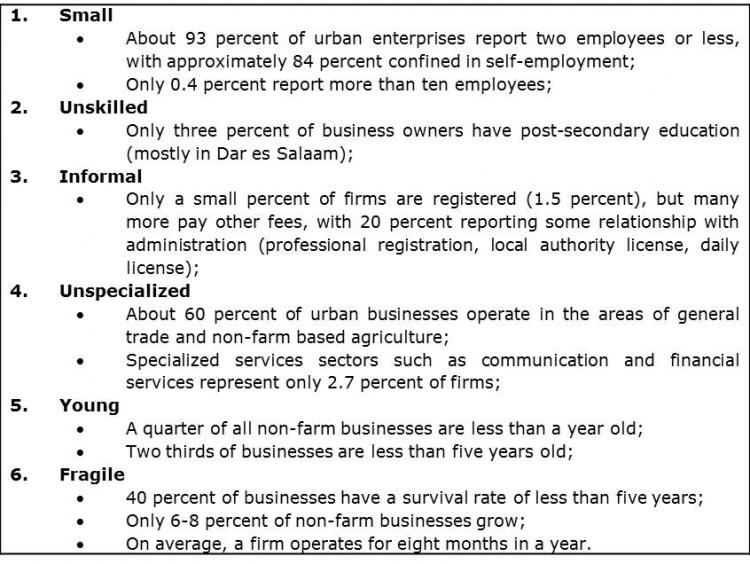

This is also very much a reality in Tanzania where small business owners have few skills and limited financial and physical assets. Of the three million non-farm businesses operating in the country, almost 90% of business owners are confined in self-employment. Only 3% of business owners possess post-secondary level education. As a result, their businesses are generally small, informal, unspecialized, young and unproductive. They also tend to be extremely fragile with high exit rates, and operate sporadically during the year. Put simply, most small businesses are not well equipped to expand and become competitive.

Are all small businesses operating in Tanzania doomed to fail? The following (but admittedly few) success stories illustrate otherwise: The owner of the largest locally owned manufacturing group, the Bahkresa Group, originally began by selling bread from a tiny bakery in the streets of Dar es Salaam approximately 40 years ago. The group now employs over 2,000 people and exports all over East Africa. Other successes include Sumaria Group, Mac Group, Motisun Holdings Limited, and METL Group, all of which started as smaller family-run enterprises. Growth is also evident on a smaller scale through the recent emergence of small exporters on regional markets, where smaller firms have been able to sell steel and agro-processed products (sugar, flour, etc.) in neighboring countries. Even at the informal level, border trade is increasingly seen as a driving force behind small business expansion.

These stories emphasize that there is no blue print for the successful growth of small businesses. A few small businesses can expand into large conglomerates and thus become the engines of industrial growth and job creation over time. Another possibility is for many small firms to experience growth on a smaller scale. While less spectacular, this second type of growth cannot be dismissed. Let’s consider the numbers: if only one out of five enterprises operating with one or two employees in Tanzania today were to add one more worker over the course of a year, it would lead to the creation of over one million jobs – sufficient to absorb the number of youth joining the local labor market every year. The challenge is to identify and focus on these small enterprises with high potential to expand beyond self-employment.

The priority for Tanzanian policy makers is to give small business owners the means to become more productive. The starting principle is to enhance their assets – skills and working premises - through targeted training programs and assurance of allocated and secure work locations. Concurrently, actions must be taken to reduce the costs of physical and virtual connectivity. Greater competition in collective modes of transport would reduce costs and increase efficiencies. For example, transport costs currently absorb approximately one-third of average incomes in Dar es Salaam. Virtual connectivity to markets, networks and information can be promoted through the low-cost use of mobile phones, which is already widespread in Tanzania. Changing the environment of uncertainty in regulation is also central as small firms suffer disproportionally from administrative burden, corruption, and insecurity. Along these lines, the 5th Tanzania Economic Update offers a potential toolkit for the development of small businesses based on lessons from the country and other best international practices.

Improving the business environment is also important for investment by large firms. They represent an important direct source of employment, notably in sectors where economies of scale are important. In Tanzania, the surge in communication and finance has unambiguously created many productive job opportunities over the past few years. Large firms also promote the creation of linkages with smaller firms along the value chain. A good example of this is the local movie industry. A few large distributors sell videos to approximately 25,000 video rentals in urban and peri-urban centers, which in turn retail to individual customers as well as a rental market consisting of about 10,000 video halls. Large firms additionally promote the development of small businesses by providing them with technology and skills as well as finance through supplier credit schemes.

At the end of the day, size may not be as much a driving force for business development as the ability and propensity to create vital linkages between small and large firms. These do not only facilitate transfers of skills, know-how, and technology, but they also promote economies of scale by reducing the entry costs for small firms. For the economy as a whole, the advantages work many ways: large firms can accelerate the maturation process of small firms, while dynamic small firms bring more competition on the market and help keep large firms on their toes. The promotion of these interactions should therefore be the priority for Tanzanian policy-makers.

X-ray of businesses operating in Tanzania

Join the Conversation