How can Madagascar leverage its landscapes, seascapes, and nature-based tourism to support green, resilient, and inclusive development? The recently completed Madagascar Country Environmental Analysis offers three ways to do this.

How can Madagascar leverage its landscapes, seascapes, and nature-based tourism to support green, resilient, and inclusive development? The recently completed Madagascar Country Environmental Analysis offers three ways to do this.

Madagascar conjures up images of rich, unique biodiversity, dense forests, and the longest coastline in Africa. And so, it would come as a surprise to learn that Madagascar is one of only 22 out of 146 countries where wealth per capita—a measure of sustainability of growth—declined between 1995 and 2018, and that this decline was driven by the low productivity of the country’s natural capital base. Reversing the trend is possible. But to do so will require better management of Madagascar’s natural capital.

How can Madagascar leverage its landscapes, seascapes, and nature-based tourism to support green, resilient, and inclusive development? The recently completed Madagascar Country Environmental Analysis (CEA) offers three ways to do this.

1. Mainstreaming landscape management

Madagascar’s landscapes host agricultural production and forestry which, along with fisheries, account for approximately 25% of GDP and 75% of employment. Landscapes provide a range of other ecosystem services, such as sustaining and regulating the flow of water for irrigation, generating both electricity and water supplies, limiting flooding downstream, retaining sediment to maintain the fertility of the soil, and reducing the amount of sediment that flows into hydropower plants.

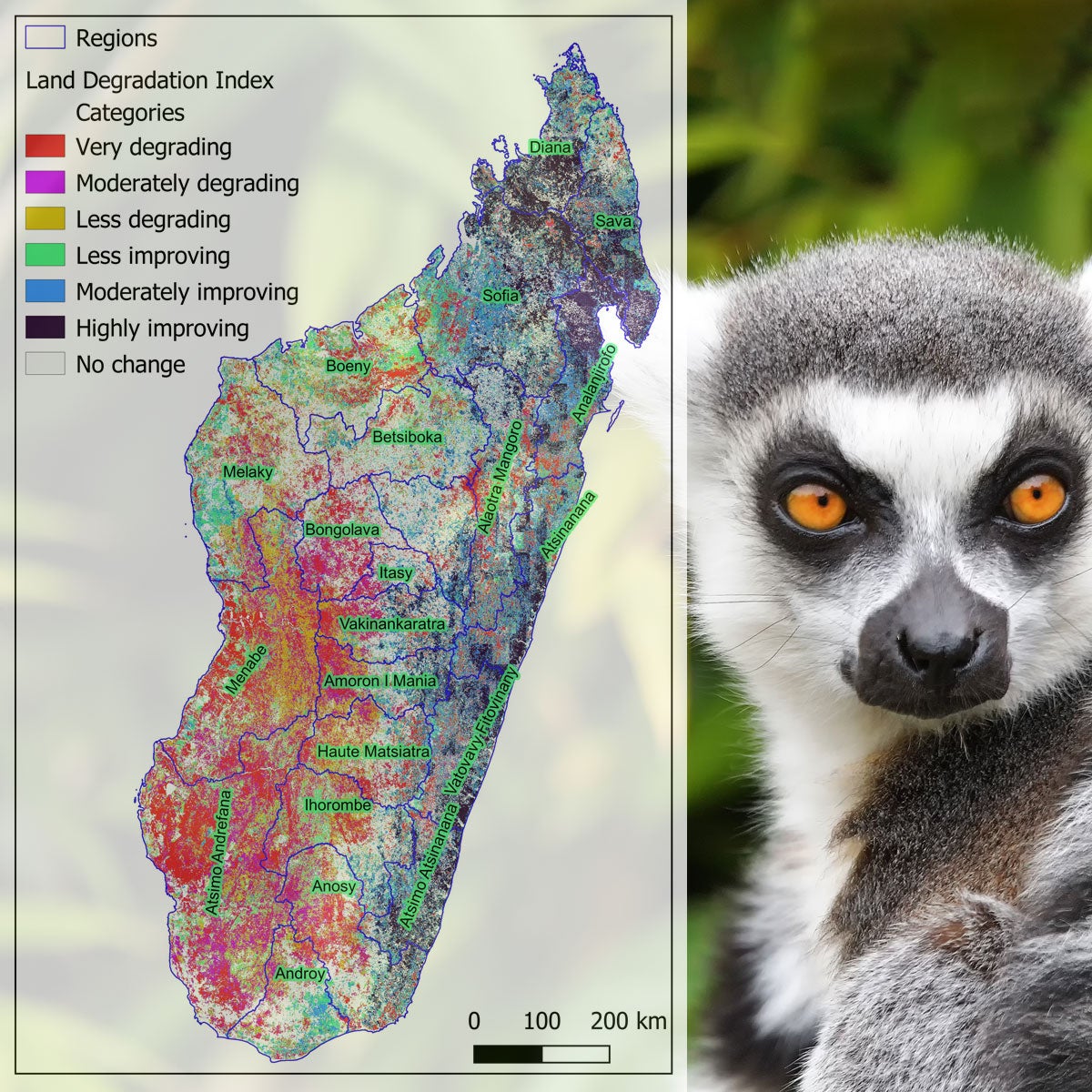

These landscapes are degrading, however (see Figure 1). Madagascar’s forest cover decreased from 29% of its land area in 2000 to 21% in 2020. Land degradation has contributed to a fall in water yield by reducing the landscape’s ability to capture and store rainfall. The economic cost of land degradation since 2000 is estimated at over $6.7 billion, amounting to 1.78% of Madagascar’s GDP a year.

Figure 1: Madagascar’s landscapes are degrading, particularly in the west and south of the country

Improvements in landscape management could increase the retention of sediment, reduce the impact of inland floods, and improve the flow of water to mitigate climate-induced changes in its availability. This would increase both carbon sequestration and efficiency of hydropower facilities. Healthy landscapes would provide both development and climate benefits.

To leverage its resources for economic growth, Madagascar needs to carry out a number of reforms, such as, mainstreaming landscape management in its rural development and infrastructure projects to in turn improve the sustainability of the infrastructure investment. A hydropower project would support investments in catchment management, for example, to reduce the flow of sediment and improve the flow of water to the reservoir.

In Madagascar, the Sustainable Landscape Management Project was the first step on the path toward integrated landscape management. The project, also known as PADAP, integrates all the elements of a typical landscape project: it is multi-functional—aimed at improving food production and the conservation of biodiversity or ecosystems, and rural livelihoods. This project has laid the ground for integrating landscape management into infrastructure projects in the country.

2. Fully realizing the potential of the Blue Economy

With 5,600 km of coastline and the fourth largest Exclusive Economic Zone in the world (over 1.22 million square kilometers), Madagascar is yet to tap the full potential of its marine capital.

Its Blue Economy is just starting to develop and is primarily focused on marine-related exports and fisheries. But the health of these ecosystems is at risk from pollution, overexploitation, and humanmade pressures, effects exacerbated by the impacts of climate change: increased sea-surface temperatures, the frequency and intensity of extreme climatic events, and coastal erosion.

Madagascar needs to build on its transition to a Blue Economy. This shift will dampen the impact of coastal flooding and increase carbon sequestration in its blue assets. The country has been creating the framework for this transition since 2015; its efforts include founding a Ministry of Fisheries and the Blue Economy in 2021. But it still needs more measures, including a Blue Economy strategy, Marine Spatial Plans, improving the investment climate for emerging industries, and incentivizing impact mitigation on marine ecosystems.

3. Leveraging biodiversity for nature-based tourism

The tourism industry leverages Madagascar’s astounding biodiversity, landscapes, and its unique culture, providing jobs for communities living near tourism destinations, either directly (guides, drivers, and hotel and restaurant staff) or indirectly (food and services to hotels and restaurants). Tourism is a significant contributor to local, regional, and national value chains in hospitality, travel agencies, handicraft, and agriculture, as well as to park fees, tax revenues, foreign currency, and foreign direct investment.

Compared to other countries close by, Madagascar’s potential for tourism growth is significant, largely due to strong interest in coastal tourism. Protected areas—marine and terrestrial—can offer solutions to biodiversity loss and land degradation and create successful tourist attractions. Increasing financing for protected area management and operations, finalizing the legal framework for tourist concessions in protected areas, and reassessing benefit-sharing arrangements with local communities can all help expand the sector, making it inclusive and sustainable. In this way, it becomes more of a contributor to economic growth while conserving biodiversity. The growth of the tourism would also shift the structure of the economy away from the more climate vulnerable agriculture sector.

In light of the multiple environmental, natural resources, and climate change risks Madagascar is facing and given the dependence of its population and its economy on sustainable natural resource management, it is urgent to take actions and address these challenges for Madagascar to achieve green, resilient, and inclusive development. With support from PROGREEN and PROBLUE, the Bank is continuing to work with Madagascar on this agenda: to prioritize investments in select landscapes that are most vulnerable to degradation; to support the Government’s objective of restoring mangroves along the long coastline and becoming a leader in “blue carbon”; and promoting nature-based tourism in the ongoing Economic Transformation for Inclusive Growth Project. The upcoming Madagascar Country Climate and Development Report will further explore resilience and mitigation issues of concern for the country.

Join the Conversation