"How was school today and please don’t forget to bring milk on your way back home". This simple conversation between Halima, a 36–year-old woman from Dodoma and her young daughter on their mobile phones was almost impossible 15 years ago: only 2 percent of Tanzanians had a phone and only one of two children attended a primary school (Figures). Today those figures reach 50 and almost 100 percent respectively. Daily life has evolved in Tanzania with technology and education as the main drivers.

(Click on figures to see them larger)

At first glance, improved access to education and technology has not yet produced major economic transformation. The GDP shares of agriculture, industry (including manufacturing) and services have remained approximately constant since the early 1980s (Figure). This rigidity, commonplace in Africa, contrasts sharply with the experience of emerging countries. As McMilland and Rodrik observe, "the speed with which this structural transformation takes place is the key factor that differentiates successful countries from unsuccessful ones"1.

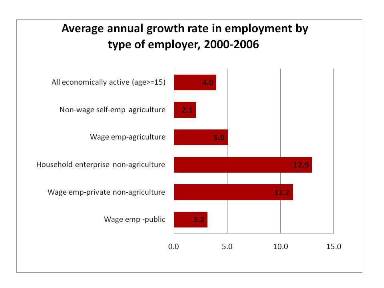

However, various emerging signs, not yet captured by national accounts, suggest the beginning of a structural transformation in Tanzania2. The first sign has been the emergence of new small, often informal, firms that have become the fastest growing source of employment in the country3 (Figure). In parallel, manufactured exports have multiplied by four since 2005 (Figure). Firms have more options for financing, not only through more active commercial banks but also new players (microfinance institutions, China) as well as the regional stock market.

Lastly, the agricultural sector might be on the verge of a breakthrough thanks to the use of ICT to farm contracts, new irrigation techniques and the willingness to break the isolation of farmers from input and consumer markets.

The signs are subtle but real and encouraging. They have been at the heart of the economic drive observed in emerging countries, such as Malaysia. The success of these countries also informs us that those signs are very sensitive to the policy environment in which they are embedded. They can strive in a good context but decline or even disappear if the right incentives are not offered by the Government.

In Tanzania, the following principles will be key to creating a virtuous circle of growth.

(i) Promote what is already moving. The private sector is generally better than the Government at picking winners and avoiding losers. Small, innovative firms offer not only opportunities for productivity gains but also employment4. The authorities should aim at reducing ther business constraints, including interventions that address market failures, but in a way that promotes competition5.

(ii) Skill and technology transfers bring high dividends. Any incentive to attract new investors (both local and foreign) should be aimed at upgrading the country's human and technological stocks. As the experience of the Asian tigers shows, every trained worker becomes a teacher or an entrepreneur, who will then be able to better use new technologies and machines6.

(iii) What and where you export matters. The recent boom in manufacturing is good news. It should lead to a diversification of products and destinations, decoupling Tanzania with the business cycle of industrial countries and giving the possibility to exploit new markets in the region and in Asia.

These three basic principles are important individually but their combination will make a difference. Promoting what is moving can only be sustained through productivity gains that require skill and technology improvements. Exports can bring those improvements and help encourage firms’ growth or creation. These principles are already applied by the Tanzanian Government, with the recent national strategies emphasizing tourism and mining--two sectors clearly on the move--but permanent attention will be required to mitigate vested interests and political interference.

The phone conversation between Halima and her daughter represents a beginning not only in Tanzania but all around Sub-Saharan Africa. More people are using internet and modern transport, making (virtual and physical) connectivity a reality. Urbanization will foster agglomeration effects and facilitate the movements of goods, services, and ideas. Education and technological progress are like tectonic plates: they move slowly but produce irreversible structural changes in the way people live, communicate and think.

---------------

1.McMillan, M. and D. Rodrik, 2011. Globalization, Structural Change and Productivity Growth, mimeo, February.

2. Those signs do not account for Tanzania’s good prospects to become a major producer of natural gas by the end of the decade.

3. For a detailed discussion, see recent paper by J. Kweka and L. Fox, The Household Enterprise Sector in Tanzania: Why It Matters and Who Cares, World Bank Policy Research Series, n. 5882, November 2011

4. M. Dutz, I. Kessides, S. O’Connel, and R. Willig, Competition and Innovation Driven Inclusive Growth, World Bank. Policy Research Working Paper, N. 5852, 2011.

5. P. Aghion et al., Industrial Policy and Competition, mimeo, June 2011.

6.These complementarities between skills and capital are at the basis I economic development for Damon Acemoglu. See, D. Acemoglu and F. Zilibotti, Productivity Differences, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, pp. 563-606.May 2001

Join the Conversation