Africa’s emergence is the new consensus. For the second time in a just few months, a major international journal has run a cover illustrating newfound optimism about the continent. After The Economist’s mea culpa (correcting its previous assessment of a “hopeless continent”), TIME magazine just re-ran an earlier title: “Africa rising”.

Africa’s emergence is the new consensus. For the second time in a just few months, a major international journal has run a cover illustrating newfound optimism about the continent. After The Economist’s mea culpa (correcting its previous assessment of a “hopeless continent”), TIME magazine just re-ran an earlier title: “Africa rising”.

This is no fluke: Africa’s economies are growing and the continent is much wealthier today than it ever was – even though, collectively, it remains the poorest on the planet. Many African nations (22 to be precise) have already reached Middle Income Country (so called “MIC”) status and more will do so by 2025. Today, Africa includes a diverse “mix” of countries, ranging from the poorest in the world to the fastest growing; from war-torn countries to vibrant democracies; from oil-rich economies to ICT champions, and the list goes on.

This has important implications for the “aid architecture”. Until now, Africa was at the center of global aid attention. But what if Africa continues to grow strongly and steadily? What will be the role of international partners (often called “donors”) in this new configuration? Is aid becoming obsolete? I don’t think so, rather the opposite! Many Africans still experience deep poverty. The challenge is so huge that ten years of moderately strong growth are just a down-payment in the fight against poverty. Today, some 400 million Africans (roughly 40% of the total population) still live on US$ 1.25 a day or less. Newfound wealth means little to them if it is not equitably spread out. Some countries are becoming richer, often as a result of oil discoveries, with very little changes in the lives of average citizens.

Fundamentally, if the poor remain neglected, a country’s development outlook has not changed. What is new, however, is that some of these MICs no longer need aid money to fill development gaps. In principle, they have enough internal resources. Yet they still need assistance in designing programs that help them spend their new resources efficiently, especially if they wish to target the poor. Aid programs, if designed well, can help do precisely this.

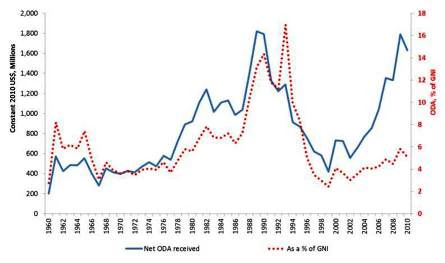

Kenya is a perfect illustration of this new aid reality. Today, Kenya’s budget is roughly US$ 12 billion, about 30 percent of the country’s economy. This share is one of the highest in Africa, making the state the biggest player in the economy. Donors are small players in comparison even though the amount of aid recovered over the last ten years after a sharp decline in the 1990s (see figure). Today, aid to Kenya is around US$ 1.5 billion (amounting to a little over 10 percent of total expenditures) of which only half is reflected in the budget. Bilateral partners like the USA and China still prefer to implement their programs outside of government systems; likewise new players, especially NGOs, typically choose to execute their programs directly (rather than through the administration).

Figure – Despite absolute increases, Kenya’s aid remains at 5 percent of GDP (Click on the graph to see it larger)

Source: World Bank estimates

So what needs to change in the way aid is being delivered? How can it be made not only relevant still but even more effective than in the past?

First, we need to acknowledge (and celebrate!) the demise of the old North-South paradigm. With Asia’s emergence – and China’s spectacular turnaround – former recipients of aid are now new donors. The previous regime, with rich countries in the North supporting poor countries in the South through government-to-government and multilateral relationships, is changing rapidly. Today, relationships are much more complex and varied, and there is a host of new players on the pitch.

Second, aid will be increasingly about transferring knowledge rather than money. No matter how significantly some donors may scale-up their financial commitments, aid money will remain small compared to domestic resources in recipient countries. If current trends continue, most of today’s stable low-income countries will reach MIC status by 2025. Going forward “traditional aid” (of the brick-and-mortar type) will focus increasingly on emergencies and fragile states. In others, transferring know-how and skills will be the name of the game.

Third, innovation and support to country systems will drive the impact of future aid. By 2025, Africa will have a majority of MICs. But as countries climb up the income ladder, they will face new and more complex policy challenges. In order not to stay stuck in the “Middle Income Trap”, African countries will need to innovate, including in traditional sectors, such as education, health or transport. The resources will be there but the challenge will be to make sure services are actually delivered and at good quality. In these countries, aid should move from building monuments (schools, clinics and roads) to improving the machine room (the systems through which education, health and transport are being provided).

Simply put: If we continue to equate aid with money only, then it will become obsolete in most countries over the next decade or two – except perhaps in fragile states. However, if it is focused on transferring the knowledge countries need to catch up and compete with each other, it will remain indispensable.

-------------------------------

Follow Wolfgang Fengler on Twitter@wolfgangfengler.

Join the Conversation