The number of COVID-19 (coronavirus) cases has exceeded 180 million worldwide and is still rising, with the economic downturn pushing 88 to 115 million people into extreme poverty in 2020, reversing the gains in global poverty reduction for the first time in a generation.

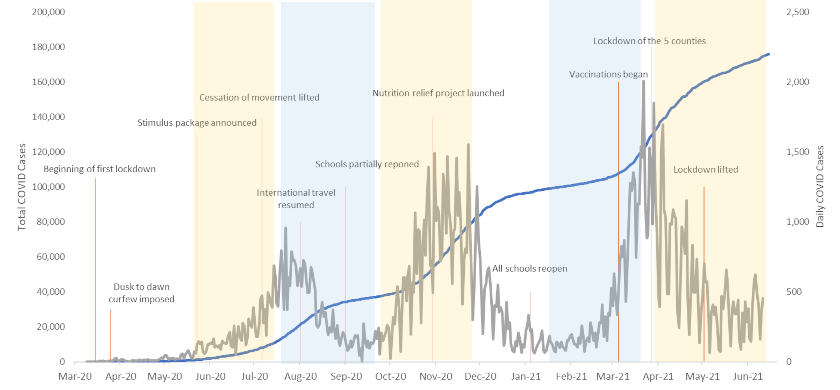

Kenya—which the World Health Organization says now exceeds 210,000 cases --has taken several steps early on to reduce the spread of the pandemic such as restrictions on movement, closure of schools, and bans on social gatherings. Restrictions were first put in place on March 12, 2020 and eased towards the end of 2020 when the number of COVID-19 cases started to drop. However, cases rose again early 2021 necessitating a second lockdown announced for five counties – including the capital Nairobi–on March 24. On May 2, 2021, the lockdown was lifted again allowing for openings of bars and restaurants, religious services, and schools as infection reduced.

To measure the socioeconomic effects of the pandemic and inform mitigation and recovery strategies, the World Bank has launched a Rapid Response Phone Surveys (RRPS) in collaboration with the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and University of California, Berkeley. The bi-monthly survey started in May 2020 and includes Kenyan nationals, refugees, and stateless households. Five rounds of the RRPS are completed and the sixth round is currently ongoing. Weekly results of the survey can be seen in an online dashboard.

Figure 1. COVID-19 cases and RRPS timeline in Kenya

Kenyans followed various preventive measures to curb the spread of the virus as the pandemic began. However, as restrictions on movement continued and the number of COVID-19 infections decreased, ‘pandemic fatigue’ reduced compliance with physical distancing measures such as avoiding large groups (dropping from 99%to 73%) and staying at home (dropping from 66% to 27%). Nevertheless, when a second lockdown was put in place, compliance with avoiding groups increased (to 84%) as well as hygiene measures such as avoiding handshakes, handwashing and wearing masks (all above 80%).

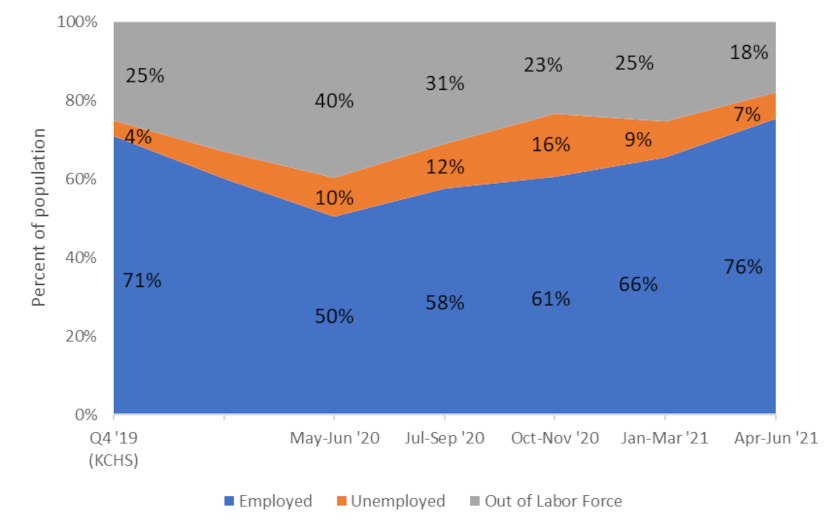

The pandemic and the related restrictions had a strong impact on the livelihoods of Kenyan households. Employment reduced from 71% to 50% at the start of the pandemic in May–June 2020, whereby the largest employment shock was felt in urban areas and among the more educated part of the population. However, employment bounced back to 76% in April–June 2021. Labor force participation also reached the highest level since the start of the pandemic in April–June 2021 (82%).

Figure 2. Labor Force Statistics (Age 18-64 years)

The employment shock created a huge reduction in earnings, resulting in a dire need to find alternative ways to cope with the effects of the pandemic. Households started to rely on their savings and reduced their food consumption at the start of the pandemic. As their saving started to deplete, many reduced their nonfood consumption and started to seek additional income generating activities to cope with the economic effect of the pandemic. More than one-fourth of the households were seeking additional income generating activities in April–June 2021. The continued use of coping mechanisms, even a year after the pandemic, indicates that many are still dealing with the consequences of the pandemic.

In line with the observed coping strategies, food consumption reduced for many Kenyan households, leading to high levels of food insecurity. Almost every second Kenyan had not enough food at the beginning of the crisis. The situation improved in October – November 2020 when less than 1 in 3 Kenyans remained food insecure. However, since January 2021 food insecurity is on the rise again almost reaching levels almost similar to the beginning of the crisis. Poor and rural households are generally more food insecure. The shortage of food directly impacts the ability of adults and children to undertake a normal, healthy, and productive life, thus leading to malnutrition, stunting, and human capital losses that can be irreversible especially for children.

Figure 3. Went hungry due to lack of food (past 30 days)

Access to education services remained compromised throughout 2020, as schools were closed, and students had to rely on self-directed learning in 2020. When schools re-opened in Kenya on January 4, 2021, 95% of the children aged between 5 to 17 years attended school. Nevertheless, the increased access to learning was short termed as schools in Kenya closed again between March 19 and May 10, 2021 due to increasing number of infections, leaving only few children learning (16%). When schools re-opened, the proportion of the children engaged in learning rebounded. This inconsistency in children’s education can have long term and serious effects on human capital, as children struggle to catch up on missed learning.

The pandemic has shaken the daily lives of Kenyans. It has impacted the way people live their lives from income to food to education. Although the recovery–especially in the labor market—is in progress, a full-fledged recovery is a long way from here while the consequences of the impacts, especially on education, will still need to be addressed.

Join the Conversation